The Abstract is the condensed version of a scientific paper. The target audience is the senior research community in the same field. Thus the vocabulary is complex and for novices and outsiders usually not understandable. It feels like visiting a huge buzzling foreign city for the first time without a map and trying to find the way to the hotel without knowing the local language and not understanding the street signs.

It takes great effort at the beginning to extract value from reading abstracts and doing so persistently. As an outsider in this research area and with many other commitments elsewhere I need an effective and efficent method to read and digest scientific abstracts despite time and mental energy constraints.

This method helps me to stay on course even in the worst and busiest moments.

I demonstrate the method on a concrete example.

Example: A Radiative-Convective Model for Terrestrial Planets with Self-Consistent Patchy Clouds

Read the last sentence of the abstract first (Update 17 August 2024)

It will summarize the key result of the paper

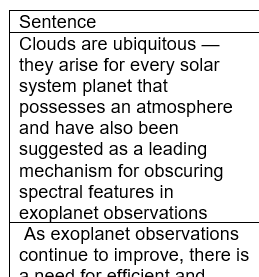

Break the abstract into single sentences.

I copy the abstract into word and then use convert text to table with the sentence point as delimeter and number of rows 1.

The result looks like this

To the initial table I add three more rows. The first row is labled section, the second row input and the third row output.

If I have two spare minutes or more, I can return to the table at any time and continue the analysis; sentence by sentence.

Identify the sections – Introduction, Result, Discussion

Scientific papers usually have similar structures, but I always check before I fill in the section column. And usually I follow a certain sequence which is not from top of the table to the bottom.

In the first step I will identify all the sentences that would belong to the introduction section of the paper. Next I would go to the end of the table and assign all the rows that belong to the result and the discussion section.

Define the Output then Input per sentence

Each sentence usually has an output and an input content. In this step I will go back to the sentences that are part of the introduction and will start my output – input analysis; in this order. I always look for the output first before defining what the input is.

In my concrete example the output is “Exoplanet observations with obscured”- (meaning: keep from being seen like gray cloud obscuring the sun) – “spectral features”. While I note down the output I might immediately decypher complex vocabulary, that I do not yet fully understand and replace it with easier words.

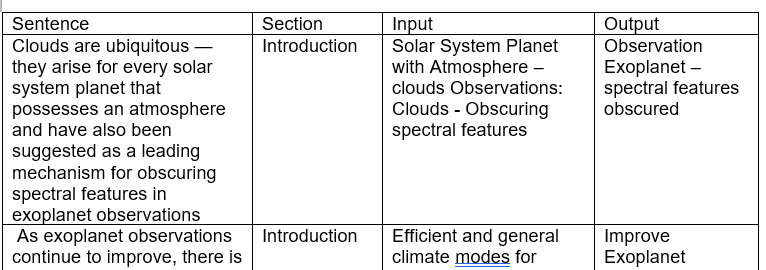

Once done with the sentences of the introduction I would jump to the section results, discussion and/or conclusion and work through it the same way as in the introduction.

As you have noticed by now the largest part, the method section will come last. The method section is mainly relevant for those readers who want to replicate the results of the research paper. Often the method section can be skipped.

Highlighting words in the abstract

Additionally I would check the title and where in the abstract the terms or words in the title are mentioned. The same I will do for the key words and highlight those in the table as well.

In the final step I will prepare all these structured information for my visual brain. Usually it is easier and faster to remember visuals and patterns then concepts and text. So for every output I will identify visual representation and I might as well do it for the input factors. One place to start is in the paper itself but if it is not sufficient I would turn to Google Image search or use AI such as Stable Diffusion to generate visuals. The key driving question to identify those visuals is, what are the key figures, images, pattern, slides that would best describe the result, discussion and logical reasoning of this paper?

Visual Processing: Example Title and Result section

The title of the paper consist of an input and an output part:

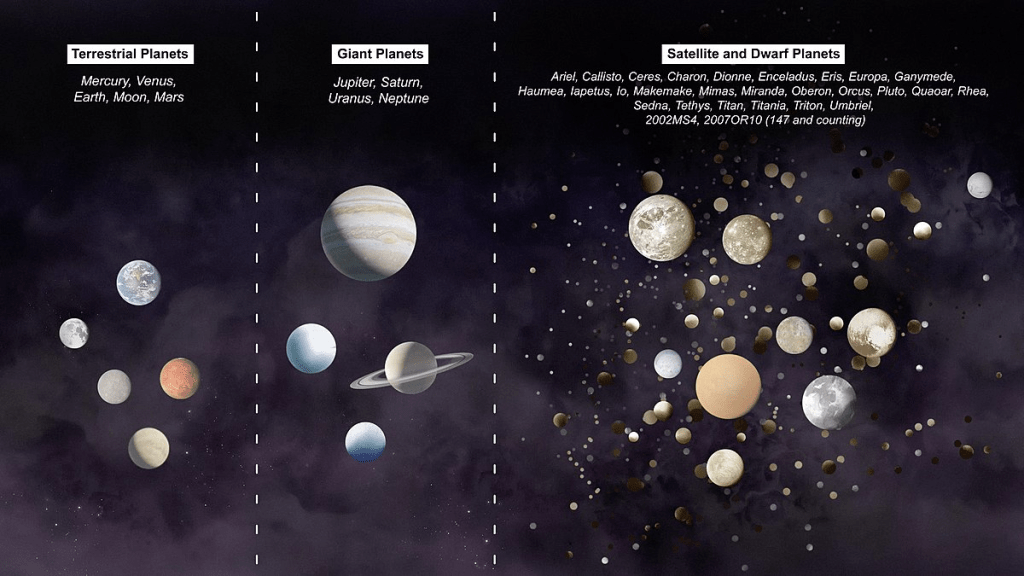

Patchy Clouds (Input):

Terrestrial Planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars (Input)

Example: World Map in a one dimensaional view (1D)

1 D Radiative Model (Output)

In a 1 D = one dimensional model the ball (the three dimensional) shape of the earth or any other planet is neglected. A sort of “flat earth” perspecitve is taken and the climate is seen as a number of layers on top of each other towering this flat model structure. Each layer is seen as the average of the climate at that altitude. This simplification is taken to optimize computation.

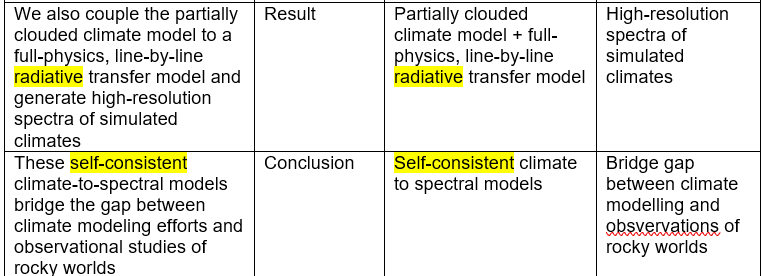

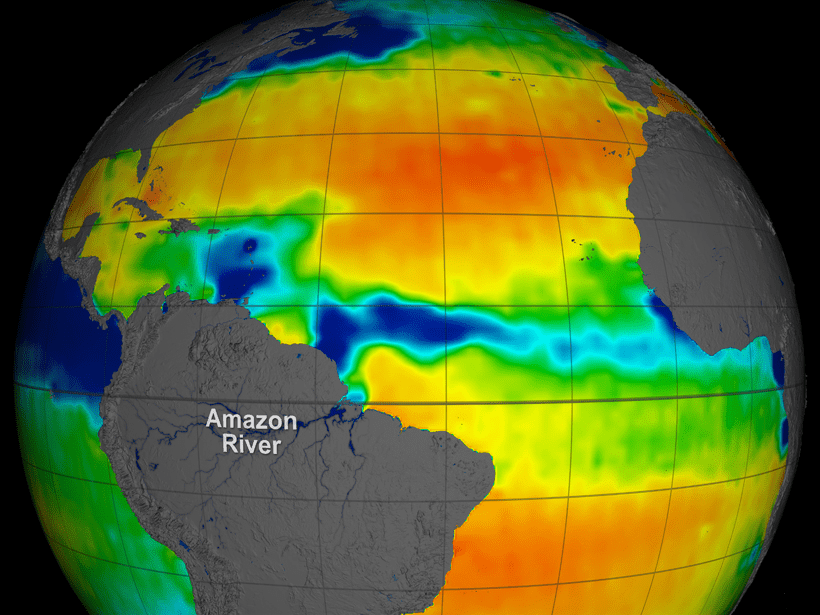

Image Reference

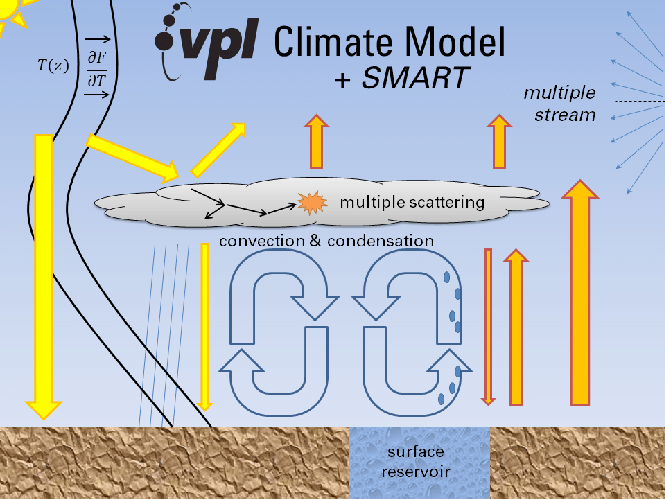

Shows how cloud will reduce the radiation of the planet. Below the clouds convection zones will form.

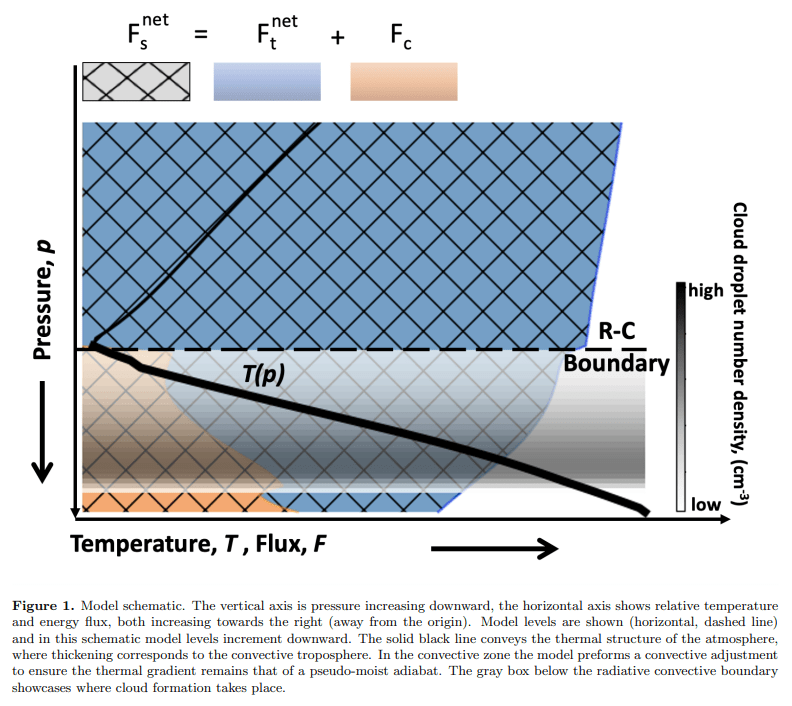

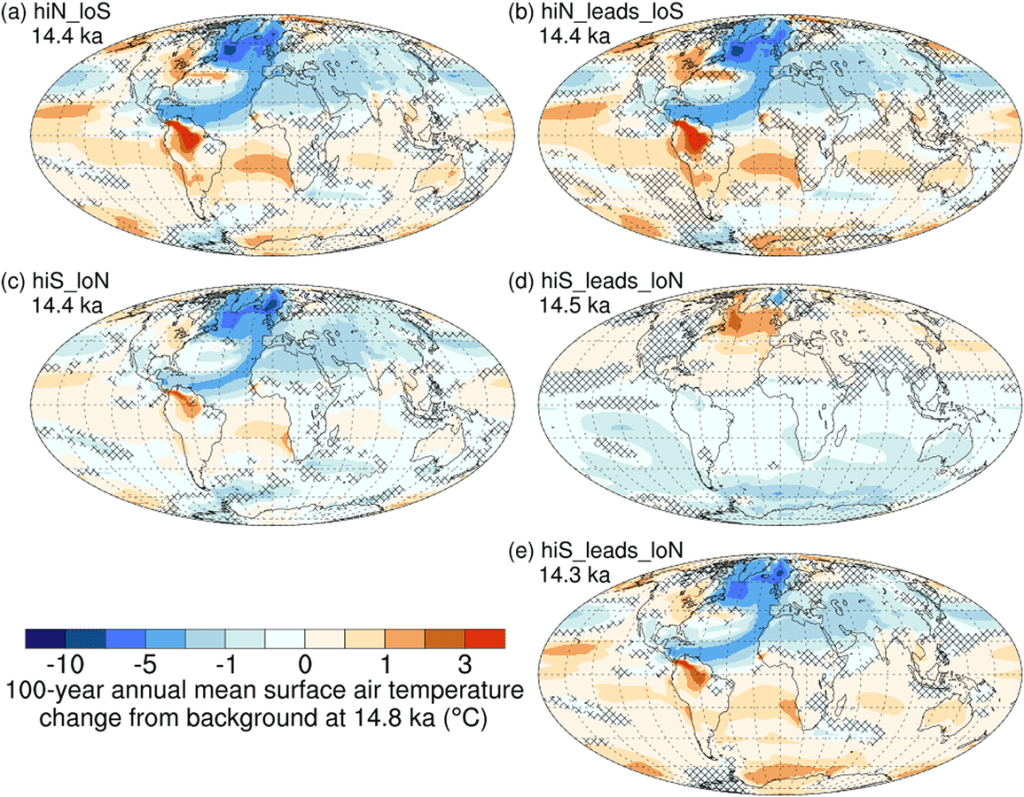

Result: Radiative-convective model (Output) – see page 6 in the paper

F the flux of radiative energy through each layer with clouds

Clouds can form under these conditions and are shown in the diagram by the gray box. The key conditions are certain pressure (range) at a certain temperature (range). And the change in gray colour represents the density of the cloud droplets in the cloud.

High resolution spectra example (Result Output) :

or AI generated with Stable Diffusion :

Simulated Climate example (Result Output):

This may look like a slow process, yet it is quite the opposite. In order to speed it up is to slow down first, which is rather counter-intuitive. With every new abstract in this topic area, the process will become easier and faster.

Maintaining the flow keeps the momemtum

Aim of the method is to keep the flow even under the worst conditions by breaking it into very small steps (example sentences) and switching between mental demanding (e.g. analysing the sentence) and less demanding tasks (e.g. finding an image). These steps can be performed whenever there is a short window of opportunity for example waiting for the next meeting, waiting for a bus, etc. The idea is to never have to schedule time for reading an abstract or to wait for the ideal moment to come.

Productivity rule: One piece flow versus backlog building

Instead of piling up a backlog of papers in the initial search, work on one paper first until completion of the analysis before looking for the next paper.

Reading an abstract this way is ideal for scoping research and searching for new research questions to address. In this case looking additionally at the discussion section towards the end of the paper and there mainly at the future work section will help identifying the open research questions.

If you do already have a research topic and are working on a literature review, not all detailed steps of such an anlaysis are needed. At any point of the reading you might come to the conclusion that this paper is not helping your research topic and therefore you will turn to the next paper.

Appendix:

The overall table of the abstract.

| Sentence | Section | Input | Output |

| Clouds are ubiquitous — they arise for every solar system planet that possesses an atmosphere and have also been suggested as a leading mechanism for obscuring spectral features in exoplanet observations | Introduction | Solar System Planet with Atmosphere – clouds Observations: Clouds – Obscuring spectral features | Observation Exoplanet – spectral features obscured |

| As exoplanet observations continue to improve, there is a need for efficient and general planetary climate models that appropriately handle the possible cloudy atmospheric environments that arise on these worlds | Introduction | Efficient and general climate modes for cloudy atmospheric environments | Improve Exoplanet observation |

| We generate a new 1D radiative-convective terrestrial planet climate model that selfconsistently handles patchy clouds through a parameterized microphysical treatment of condensation and sedimentation processes | Method | Condensation and sedimatation processes Patchy Clouds Selfconsistently handled through a parametrized microphysical treatment | 1D radiative-convective terrestrial planet climate model |

| Our model is general enough to recreate Earth’s atmospheric radiative environment without over-parameterization, while also maintaining a simple implementation that is applicable to a wide range of atmospheric compositions and physical planetary properties | Method | Model without overparamterization, wide range of atmospheric composition and planetary properties | Recreate Earth’s atmospheric radiative environment; implementation for other planets with atmosphere |

| We first validate this new 1D patchy cloud radiative-convective climate model by comparing it to Earth thermal structure data and to existing climate and radiative transfer tools | Method | Comparison to thermal earth structure data and to existing climate and radiative transfer tools | 1D patchy cloud radiative-convective climate model validated |

| We produce partially-clouded Earth-like climates with cloud structures that are representative of deep tropospheric convection and are adequate 1D representations of clouds within rocky planet atmospheres | Method | Partially.clouded Earth like climates with cloud structures of deep tropospheric convection | 1D Earth-like climates with cloud structures for rocky planets with atmosphere |

| After validation against Earth, we then use our partially clouded climate model and explore the potential climates of superEarth exoplanets with secondary nitrogen-dominated atmospheres which we assume are abiotic | Method | Validated partially clouded climate model | Climates of superEarth exoplanets with nitrogen-dominated atmospheres and no life |

| We also couple the partially clouded climate model to a full-physics, line-by-line radiative transfer model and generate high-resolution spectra of simulated climates | Result | Partially clouded climate model + full-physics, line-by-line radiative transfer model | High-resolution spectra of simulated climates |

| These self-consistent climate-to-spectral models bridge the gap between climate modeling efforts and observational studies of rocky worlds | Conclusion | Self-consistent climate to spectral models | Bridge gap between climate modelling and obsvervations of rocky worlds |

The output and input might be messy in the first pass. With each new pass through it will get clearer.

Further AI assisted Reading

Semantic Scholar | Semantic Reader

AI-Powered Augmented Scientific Reading Application to overcome the following obstacles:

- Frequently paging back and forth looking for the details of cited papers

- Challenges recognizing the same work across multiple papers

- Losing track of reading history and notes

- Contending with a PDF format that is not well suited to mobile reading or assistive technologies such as screen readers

AI assisted Literature Review Process