Update 06.09.2025: Conceptual Witepaper on the plan to solve the millenium prize problem.

Do you believe that only mathematicians can solve these problems?

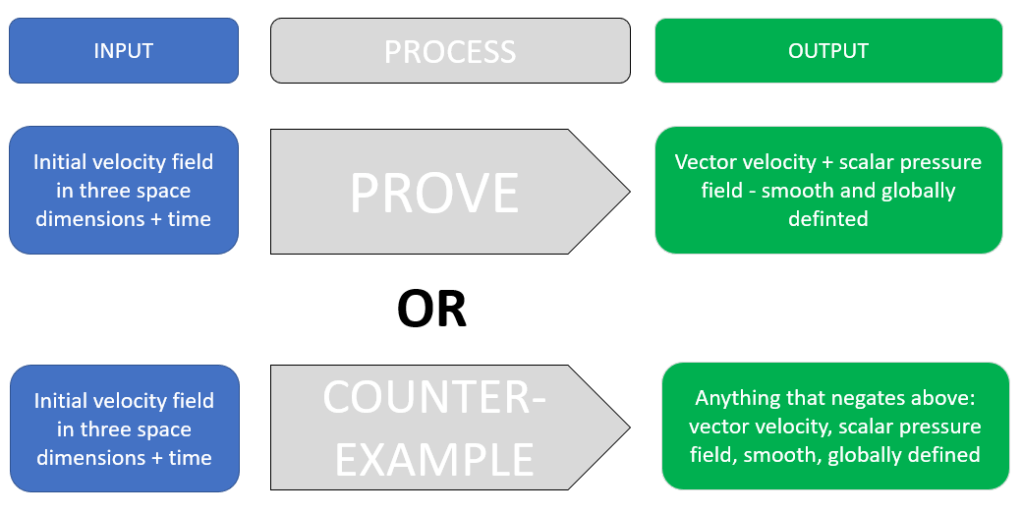

The Clay Mathematics Institute of Cambridge, Massachusetts (CMI) set out a million dollar prize in May, 2000 for anyone to:

Prove or give a counter-example of the following statement:

In three space dimensions and time, given an initial velocity field, there exists a vector velocity and a scalar pressure field, which are both smooth and globally defined, that solve the Navier-Stokes equations.

The incompressible Navier-Stokes equations are given by – Official Problem Description:

- Momentum equation (conservation of momentum): ∂t∂u+(u⋅∇)u=−∇p+νΔu+f, where:

- u=u(x,t) is the velocity field of the fluid,

- p=p(x,t) is the pressure field,

- ν>0 is the kinematic viscosity,

- f=f(x,t) is the external force per unit volume,

- x∈R3 is the spatial coordinate,

- t≥0 is time.

- Continuity equation (incompressibility condition): ∇⋅u=0.

The Millennium Prize Problem asks whether, for smooth initial conditions u0(x) satisfying ∇⋅u0=0, there exists a globally defined, smooth solution u(x,t) and p(x,t) for all t>0. Alternatively, it asks whether singularities (blow-ups) can form in finite time.

The first counterintuitive approach in state-of-the-art problem-solving is to step back and resist the urge to immediately jump into finding solutions. Instead, the key focus should be on understanding and analyzing the problem.

Navier-Stokes: https://circularastronomy.com/2025/08/23/the-fastest-way-to-understand-any-mathematical-function/

There are many ways to go about problem solving

The idea is to ask the most effective and least amount of questions in optimal sequence to extract as much information as possible.

Major questions to ask before starting the problem-solution process:

- How much time is available to solve the problem?

- What is the environment surrounding the problem?

- What is the current state of the problem?

- Are there alternative problems to consider?

- Have these alternative problems been solved yet?

Using Systems Thinking to Approach the Problem

Solving a system’s problem in nature:

The first step in systems thinking is to look outside the system. What larger system is it a part of? What is the surrounding environment?

Navier Stokes equation are part of classical mechanics and are derived from applying Newton’s second law of motion to fluid motion.

Navier-Stokes equations are widely used in engineering, meteorology, oceanography, and astrophysics to model phenomena like air flow over an airplane wing, weather patterns, ocean currents, and even the behavior of stars.

The key is to establish system boundaries in order to analyze the system itself. System boundaries define the systems properties. The following questions can help identify these boundaries.

What is a FlUID and when it is not a FLUID?

First, describe the distinction between fluid and non-fluid in natural language, and then use mathematical abstractions to define these concepts.

Fluids are substances that flow and take the shape of their container. Fluids can be liquids or gases. Plasma is also a fluid, but it is not covered by the Navier-Stokes Equation.

Archimedes, a Greek mathematician and engineer, laid the foundation for fluid mechanics with his discovery of buoyancy. His famous principle states that an object submerged in a fluid experiences an upward force equal to the weight of the displaced fluid.

Al-Khazini and Al-Biruni expanded on Archimedes’ work. They studied fluid density, pressure, and hydrostatics, applying these principles to engineering and astronomy.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519): Da Vinci studied the motion of water and air, observing turbulence, vortices, and wave patterns. He sketched detailed diagrams of fluid flow, laying the groundwork for modern fluid dynamics.

Evangelista Torricelli (1643): Torricelli invented the barometer and demonstrated that air has weight, leading to the study of atmospheric pressure.

Blaise Pascal (1653): Pascal formulated the principle of fluid pressure, stating that pressure applied to a confined fluid is transmitted equally in all directions (Pascal’s Law).

Daniel Bernoulli (1738): Bernoulli’s Principle, published in Hydrodynamica, describes how fluid pressure decreases as its velocity increases.

Leonhard Euler (1757): Euler developed the Euler equations, which describe the motion of ideal (non-viscous) fluids.

Claude-Louis Navier (1822) and George Gabriel Stokes (1845): They extended Euler’s work by incorporating viscosity, leading to the Navier-Stokes equation, which describes the motion of real (viscous) fluids.

Osborne Reynolds (1883): Reynolds studied the transition between laminar (smooth) and turbulent (chaotic) flow, introducing the Reynolds number, a dimensionless quantity that predicts flow behavior.

Ludwig Prandtl (1904): Prandtl introduced the concept of the boundary layer, explaining how fluid flows near surfaces like airplane wings.

When Is a Substance Not a Fluid?

Solids resist deformation and maintain a fixed shape under shear stress. Some materials, like rubber or clay, can deform under stress but do not flow continuously. Glass is sometimes called an “amorphous solid” because it behaves like a solid on short timescales but flows extremely slowly over long timescales. Substances like sand or grains can flow under certain conditions (e.g., in an hourglass), but they are not true fluids because their flow depends on particle interactions rather than continuous deformation.

Non-Newtonian Solids: Some materials, like oobleck (a cornstarch-water mixture), behave like a solid under certain conditions (e.g., when struck quickly) and like a fluid under others. These are complex materials that blur the line between solids and fluids.

What is incompressible and when is it not?

First, describe the distinction between liquid and non-liquid in natural language, and then use mathematical abstractions to define these concepts.

What is a incompressible fluid and when it is not?

First, describe the distinction between liquid and non-liquid in natural language, and then use mathematical abstractions to define these concepts.

What is motion and when it is not?

First, describe the distinction between liquid and non-liquid in natural language, and then use mathematical abstractions to define these concepts.

See also hydrostatics (fluids at rest) : Archimedean screw

Based on the answers above, analyze existing mathematical papers on the Navier-Stokes equation and the Millennium Prize Problem.

In the next step, focus on examining the system itself, including its underlying paradigms.

Use natural language to describe the incompressible Navier-Stokes equation:

Imagine you are observing a fluid, like water or air, moving through space.

The change in velocity over time (how the fluid speeds up or slows down) is caused by:

- The fluid carrying itself along,

- Pressure differences pushing the fluid,

- Viscosity smoothing out the motion

- External forces acting on the fluid.

At every point in the fluid, there is a velocity that tells you how fast and in what direction the fluid is moving.

This velocity changes over time and space.

What we want to understand what causes these changes.

- Start by looking at how the velocity at a point changes over time. “How does the speed and direction of the fluid at this spot evolve as time passes?”

- Consider how the fluid’s movement at one point is influenced by the movement of the fluid around it.

Imagine a river: the water at one spot is pushed along by the water upstream. - Pressure is like a force that pushes the fluid from areas of high pressure to areas of low pressure. If there’s a difference in pressure between two points, the fluid will accelerate toward the lower-pressure area.

- Viscosity is like the fluid’s internal resistance to motion. Imagine honey versus water: honey resists motion more because it’s more viscous.

- External forces. These could be things like wind pushing it sideways. These forces add to the motion of the fluid.

What you notice in the above descriptions is that they only consider the unidirectional flow of an incompressible liquid from a specific point onwards.

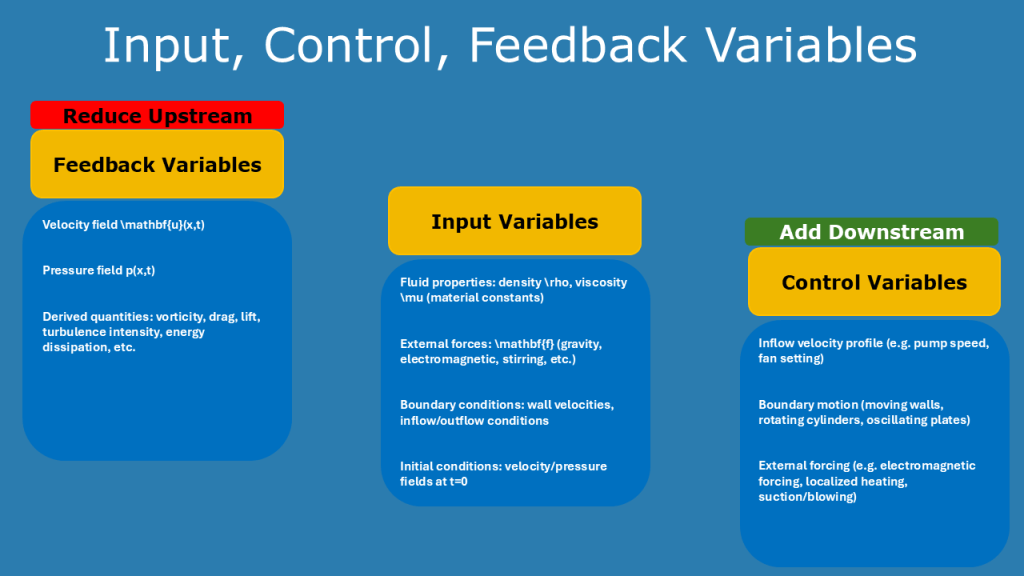

Input – Output Relationship

Another perspective involves analyzing the input-output relationship of the problem statement.

Remark: Systems Thinking was established in the 1940s and unknown to Navier and Stokes.

System rules define the systems behaviour (dynamic) and the behaviour defines and shapes the structure of the system. Vice versa the system boundaries and the environment influence the system rules and thus the behaviour. It is an oscillating interaction.

Polya’s problem solving technique in mathematics:

Polya’s approach is to start with a best guess.

Most mathematicians tend to believe that the Navier-Stokes equations will likely be proven to have smooth and globally defined solutions under the given conditions, rather than a counterexample being found.

If you examine the input-output relationship of the problem statement, the best guess seems to favor finding a counterexample rather than a proof. A likely starting point could be to search for a counterexample first, rather than attempting to prove it outright.

Let’s find out with a poll: https://strawpoll.com/XOgONlrOrn3

Backwards problem solving:

Rapid problem analysis

Inventive problem solving:

Use of AI Tools

Javier Gómez Serrano (Mathematician Brown University) teamed up with Google DeepMind Team. The team consists of 20 people who have been working on the solution for three years. On the team are two geophysicists — Ching-Yao Lai and Chinese Yongji Wang, authors of complex models for calculating melting ice in Antarctica — and additional two mathematicians: Tristan Buckmaster and Gonzalo Cao Labora.

Their attempt seems to target the boundary condition between solid and fluid.

My plan to win the Millenium prize with OpenAI:

Use the wisdom of the crowd

a) Internet searches

b) Citizen Research Communities

Use Analog Computing

Viktor Schauberger Waterflow

- Vortex geometry (spirals, implosions) might stabilize flows.

- In Navier–Stokes terms, this is equivalent to geometric alignment of vorticity — exactly one of the overlooked pieces in current approaches.

Christine Sindelar publications: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Christine-Sindelar

Conceptual Witepaper on the plan to solve the millenium prize problem.

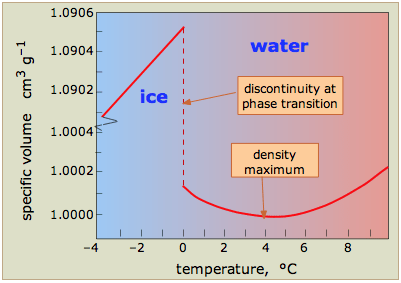

Interplay between two opposing aspects

Temperature of 273.16 K (0.01∘ C) and a partial vapor pressure of 611.657 Pa (approximately 0.006 atm).4 Below this pressure, liquid water cannot exist in a stable state. Any increase in temperature at a constant pressure below the triple point will cause ice to bypass the liquid phase and transition directly to vapor through the process of sublimation.3

Another critical state point is the critical point, where the liquid-gas boundary terminates and the two phases become indistinguishable, forming a supercritical fluid.2 For water, this occurs at a temperature of 647.096 K and a pressure of 22.064 MPa.2

A seminal study by Cheng and Lin in 2007 investigated the morphological changes of water within a vacuum cooling system, providing a precise timeline of the process.9 Their experiments showed that as the pressure in the chamber was reduced, a series of distinct events occurred: the liquid water began to produce tiny bubbles after 115.2 s, which grew larger at 121.2 s, leading to rapid boiling at 126.7 s. After the boiling subsided, the water entered the freezing stage at 181.5 s. The final ice mass, observed after 480 s, was found to have a two-layered structure: an irregular, porous layer on top and a dense layer below.9

Timeline Stages:

- 115.2 s – Bubble Formation

- 121.2 s – Larger Bubbles

- 126.7 s – Rapid Boiling

- 181.5 s – Freezing Begins

- 480 s – Final Ice Structure (Porous top layer, dense bottom layer)

laboratory experiments: a volume of water in a vacuum chamber with an insulating glass beaker is more likely to freeze than one in a conductive copper vessel, as the latter can more efficiently transfer ambient heat to the water, aiding the sublimation process after the initial freeze.6

Interplay between steepness and smoothness (Neither can be infinite or 0 in a liquid). Can be extended to the interplay of velocity and pressure (Either of it infinite or 0 will lead to no boundary layer, and no boundary layer means no liquid)

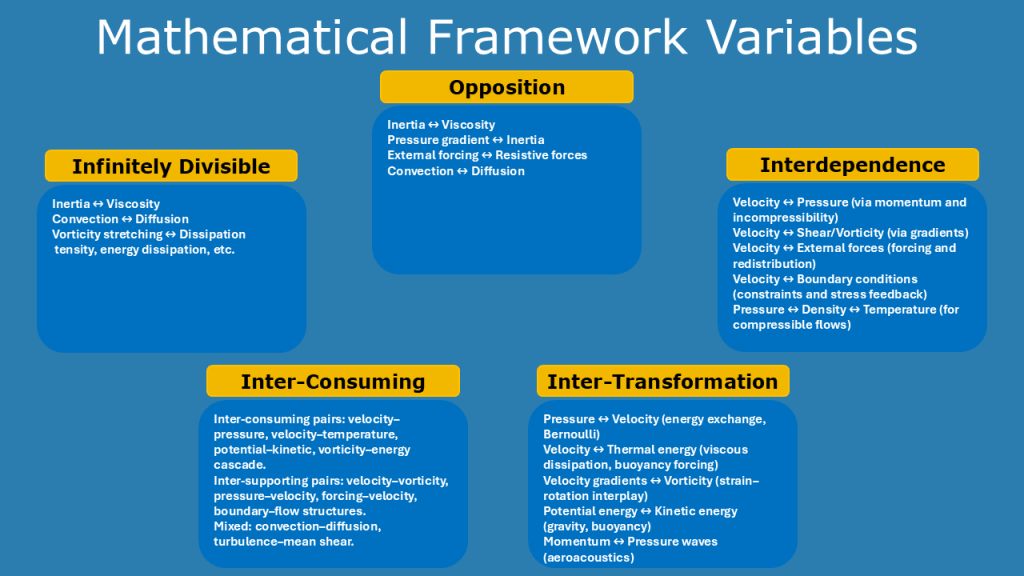

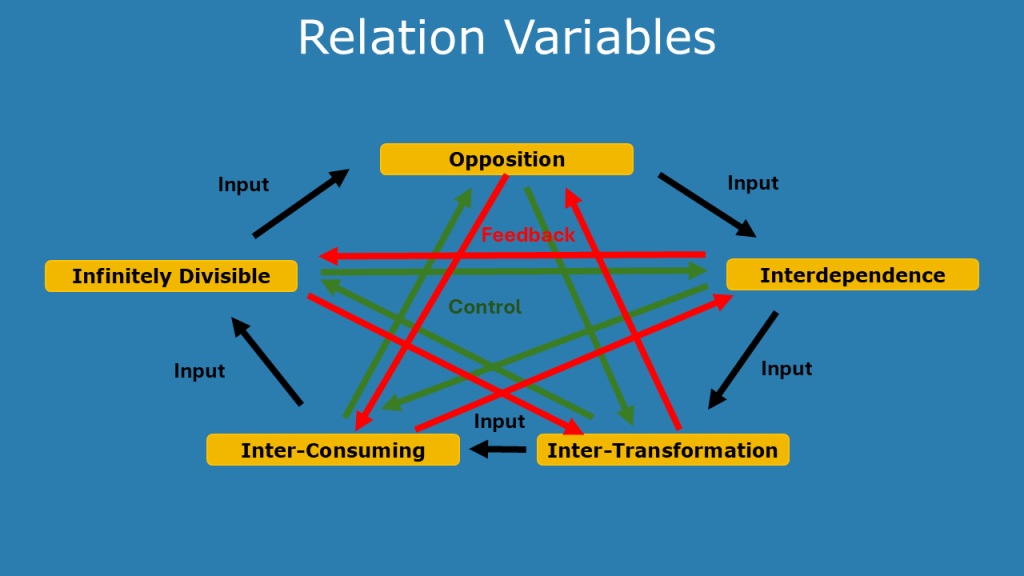

5 Postulates for Systems (Structural and Dynamic Aspects)

- Opposition: Two opposing aspects will restrict the other through opposition.

- Interdependence: Neither aspect can exist in isolation, without one there is no other and vice versa. Each aspect is the condition for the other’s existence. (Example Vacuum – no pressure no liquid)

- Inter-consuming-supporting: Continuous mutual-consumption and support between the two aspects. (Quantative change)

- Inter-transforming: In certain circumstances, either of the two aspects will transform into its opposite (Qualitive change). Extreme states of one of the aspects will eventually transform in the opposite. (Example Vacuum – part will turn into steam part into ice)

- No fundamental indivisible unit exists: Aspects are infinite divisble.

Mathematical frameworks (Dialectic dynamical inter-consuming systems)

Opposition: projective geometry, category theory, or optimization theory

Interdependence: dynamical systems (e.g. Heisenberg uncertainity principle), game theory, network theory

Inter-consuming-supporting: Lottka-Volterra(predator-prey)

Inter-transforming: nonlinear dynamics (laminar to turbulent flow), thermodynamics in vacuum, catastrophe theory (René thom)

No fundamental indivisible unit: Self similarity – Fuzzy Logic Fractal

Quantum Tornadoes

Generate Solution Options

What solution options have been published so far

Mathematical Concepts:

Nodes – (see Non Linear Equations in Differential Equations with Applications and Historical Notes – George F. Simmons Page 538: Figure 86 ) A critical point is called a node.

One response to “Using State-of-the-Art Problem Solving for the Navier-Stokes Equations”

[…] Using State of the Art Problem Solving for the Navier-Stokes Equations […]

LikeLike