The literature on vacuum liquid phase transitions provides a fascinating and relevant context for the Navier-Stokes Millennium Problem, not by offering a direct solution to the existence and smoothness of its solutions, but by highlighting the precise physical conditions under which the equations’ underlying assumptions break down.

Vacuum-Induced Phase Changes in Liquids: A Comprehensive Review of Thermodynamic Behavior and Experimental Studies

Abstract

The study of liquid phase transitions in low-pressure environments has evolved from a scientific curiosity into a critical field of inquiry with broad applications across multiple disciplines. This review synthesizes key research on the behavior of liquids in a vacuum, focusing on the interplay of thermodynamic, kinetic, and molecular-level phenomena. The report begins with an analysis of foundational principles, including boiling point depression, sublimation, and the self-cooling effect driven by latent heat. It then surveys the historical progression of experimental studies, from early observations of metal volatilization to contemporary investigations of high-speed cryogenic jets and magnetically levitated liquid droplets. The review critically examines the theoretical models developed to describe these phenomena, from macroscopic thermodynamic equations to microscopic kinetic theories and molecular dynamics simulations, highlighting their strengths and limitations. A dedicated section addresses ongoing debates, such as the paradox of simultaneous boiling and freezing, the proposed liquid-liquid phase transition in water, and the distinction between physical and cosmological vacuum states. Finally, the report identifies significant gaps in the current literature and proposes directions for future research, including the need for enhanced measurement techniques, the development of more robust computational models, and the exploration of novel fluids and quantum effects.

I. Introduction

The traditional understanding of phase transitions—the change of a substance from one state of matter to another—is based on the manipulation of temperature and pressure. For instance, water boils at a fixed temperature of 100°C at standard atmospheric pressure. However, in low-pressure environments, such as those encountered in space, industrial vacuum chambers, or at high altitudes, this straightforward relationship breaks down. The behavior of liquids under these conditions is complex, often leading to counter-intuitive outcomes where a liquid can boil and freeze simultaneously.1 This field is not merely of academic interest; it holds significant practical importance in aerospace engineering for managing cryogenic propellants, in materials science for creating advanced ceramics via freeze casting, in the food and pharmaceutical industries for freeze-drying, and in chemical engineering for vacuum distillation of sensitive compounds.3

This review provides a structured synthesis of the literature on the phase transitions of liquids in vacuum. It is organized to trace the progression of knowledge from fundamental principles to cutting-edge research. The scope extends from the macroscopic thermodynamic and fluid dynamic behaviors to the microscopic, molecular-level mechanisms that govern these transitions. The central argument presented is that the behavior of liquids in a vacuum is a complex, multi-scale phenomenon that challenges traditional models and necessitates a multidisciplinary approach combining classical thermodynamics, kinetic theory, and advanced computational methods to fully comprehend and predict these phenomena.

II. Foundational Principles of Liquid Phase Behavior in Low-Pressure Environments

A. The Thermodynamic Basis of Phase Change: Boiling Point Depression

The most direct thermodynamic consequence of a low-pressure environment is the reduction of a liquid’s boiling point. Boiling is a phase transition that occurs when a liquid’s vapor pressure—the pressure exerted by its vapor in a confined space—becomes equal to the surrounding external pressure.4 Under standard atmospheric conditions, water’s vapor pressure reaches 101.3 kPa (1 atm) at 100°C. In a vacuum, the external pressure is significantly lower, and thus, a much lower vapor pressure is required to induce boiling.7 This relationship is precisely defined by the Clausius-Clapeyron equation, which demonstrates that the boiling point of a compound decreases logarithmically with decreasing pressure.4 This principle is the cornerstone of vacuum distillation and rotary evaporation, where it enables the efficient removal of high-boiling or heat-sensitive solvents at temperatures that prevent their thermal degradation.4

B. The Triple Point and Sublimation

The phase behavior of a substance in a vacuum is governed by its phase diagram, which maps the solid, liquid, and gas states across varying temperatures and pressures.8 A critical feature of this diagram is the triple point, the specific temperature and pressure where all three phases coexist in equilibrium.8 A key thermodynamic rule dictates that a substance can only exist in its liquid phase if the surrounding pressure is greater than its triple point pressure.8 For water, the triple point occurs at 0.01°C and 611.7 Pa (4.58 Torr).9 If the pressure drops below this value, a liquid cannot exist. Instead, the substance will transition directly from its solid phase to a gas, a process known as sublimation.8 This phenomenon has been observed for a wide range of materials, including metals, which were found to volatilize at temperatures far below their normal melting points when placed in a vacuum.11

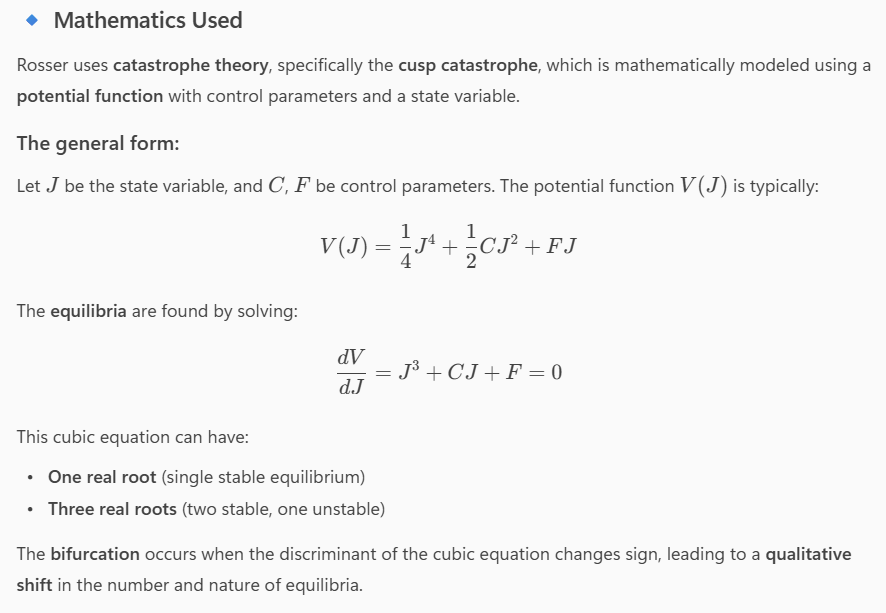

[Personal Research Note: The Quantitative-to-Qualitative Analogue: In his seminal paper, J. Barkley Rosser Jr. (1996) posits that catastrophe theory, chaos theory, and complex emergent dynamics models can all describe how a continuous change in a system parameter can lead to a discontinuous and qualitative shift in its behavior.1 A classic example is a system moving from a single stable equilibrium to three, two of which are stable and one unstable, a change that fundamentally alters the system’s dynamics.1 Rosser references the work of René Thom, who identified such structural changes with the emergence of new organs in the development of organisms, as a biological illustration of this principle.1

Mathematical Models (Theoretical Data)

Rosser uses several mathematical formulations to illustrate dialectical transformations:

A system moving from a single stable equilibrium to three:

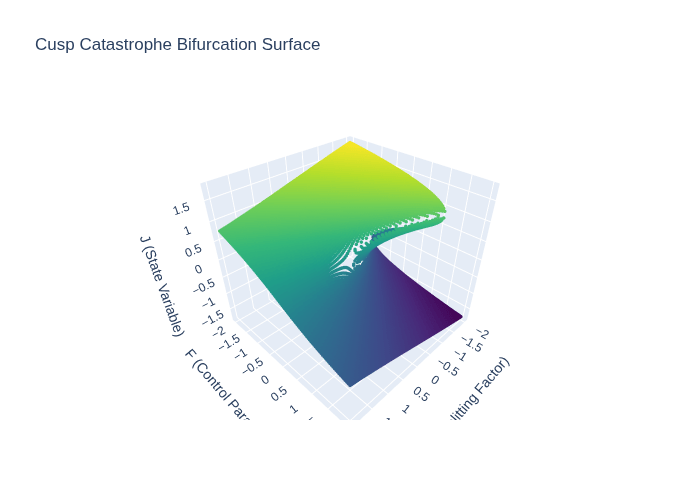

What the Plot Shows:

- Axes:

- C: Splitting factor (control parameter)

- F: Another control parameter

- J: State variable (equilibrium values)

- Dots: Represent equilibrium points for different combinations of CC and FF

- When there is one dot for a given C,FC,F, the system has a single equilibrium

- When there are three dots, the system has two stable and one unstable equilibrium

🔹 Interpretation:

- As the control parameters CC and FF change continuously, the system undergoes a bifurcation:

- It moves from a single equilibrium to a region with three equilibria

- This is a discontinuous and qualitative shift in system behavior

1. (PDF) Aspects of Dialectics and Non-linear Dynamics. – ResearchGate, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5208244_Aspects_of_Dialectics_and_Non-linear_Dynamics]

Differential equations for bifurcation analysis: dxdt=f(x)dtdx=f(x)

Cusp catastrophe model with control variables CC and FF, and state variable JJ

Logistic map for chaos: xt+1=xt(k−xt)xt+1=xt(k−xt)

Lyapunov exponents for measuring chaos: L=limt→∞ln(Dft(y)v)tL=limt→∞tln(Dft(y)v)

C. The Latent Heat of Evaporation and Self-Cooling

The most paradoxical consequence of a liquid’s behavior in a vacuum is the phenomenon of self-cooling, which can lead to simultaneous boiling and freezing. The process of phase change from a liquid to a gas requires a significant amount of energy known as the latent heat of vaporization.1 Under reduced pressure, this energy is not supplied by an external heat source but is instead drawn from the internal kinetic energy of the remaining liquid molecules.1 As the highest-energy molecules escape as vapor, the average kinetic energy of the bulk liquid decreases, causing its temperature to drop precipitously.13 This evaporative cooling effect is so efficient that the temperature of the liquid can fall below its freezing point, even while it continues to boil.1 This cascade of events—where reduced pressure leads to boiling, which in turn leads to a drop in temperature and potential freezing—is the fundamental physical mechanism that underpins many of the more complex phenomena and applications in this field.

III. A Historical and Contemporary Survey of Experimental Studies

The historical development of research on liquids in vacuum demonstrates a progression from early, qualitative demonstrations to sophisticated, quantitative studies of dynamic phenomena.

A. Early Observations and Demonstrations

The foundational understanding of liquid behavior under low pressure began with simple, yet impactful, demonstrations. The classic bell-jar experiment, a staple of physics classrooms, vividly illustrates the boiling and freezing paradox.1 By evacuating the air from a chamber containing a beaker of room-temperature water, observers can see the water begin to boil as its boiling point drops below room temperature. Subsequently, as the rapid evaporation cools the liquid, ice crystals are seen to form, demonstrating the self-cooling effect.

Early scientific investigations focused on the volatility of materials under vacuum. Demarçay’s 1882 experiments showed that metals such as cadmium and zinc volatilized at temperatures far below their melting points when subjected to low pressures.11 This concept was further explored by Kaye and Ewen in a 1913 study on the sublimation of metals.12 They identified two types of vapor emitted: a normal vapor and “rectilinear particles” that propagated in straight lines. Their work, which provided evidence of a microscopic, kinetic-level phenomenon, laid the groundwork for future theories that would distinguish between molecular and fluid-dynamic behavior.

B. Flash Evaporation in Liquid Jets and Droplets

Contemporary research has shifted from the behavior of static, bulk liquids to the more dynamic and complex phenomena of liquid jets and droplets ejected into a vacuum. This field of study, often referred to as flash evaporation or flash boiling, is crucial for applications such as rocket propulsion and spray systems.14

Luo et al. 14 conducted both experimental and numerical studies on the dispersal characteristics of liquid jets in vacuum. Their core finding was that the degree of superheat—the initial temperature of the liquid relative to its new boiling point in vacuum—is the most important parameter governing the liquid’s breakup and atomization. They also noted that jet stability decreases as ambient pressure is lowered.14 The work of Mutair and Ikegami 16 provided further detail, modeling the heat transfer process in superheated water drops. They identified a “potential core zone” near the nozzle where flash evaporation had not yet commenced and found that the violent flow within larger droplets significantly increased their effective thermal conductivity.16 An important, and at times problematic, outcome of these studies is the observation that the drastic temperature drop can cause liquid jets to solidify, a phenomenon that poses a challenge for systems like rocket engine startups.14

C. The Unique Case of Cryogenic Fluids

The principles observed with water also apply to cryogenic liquids, but with unique challenges and applications. Research into the injection of superheated cryogenic fluids like liquid nitrogen into a vacuum has confirmed that it also leads to flash boiling and potential solidification, creating issues for engine ignition.15 Similarly, studies on high-speed liquid deuterium jets found that freezing is not instantaneous but depends on the jet’s diameter and velocity.17

A significant recent advancement is the successful magnetic trapping of millimeter-scale superfluid helium drops in a high vacuum.18 This experimental setup allows for the prolonged observation of a liquid in a state of extreme thermal isolation. The drops, which are not in contact with their surroundings, cool by evaporation to an astonishingly low temperature of 330 mK, well below the ambient temperature of the chamber. This technique has enabled researchers to measure fundamental properties such as mechanical damping and the characteristics of optical whispering gallery modes in a superfluid, providing unparalleled insight into the behavior of quantum fluids.18

D. Applications in Materials and Biological Systems

The unique behavior of liquids in vacuum has been leveraged for a wide range of practical applications. Freeze-drying, or lyophilization, is a prime example, where a vacuum is used to induce the sublimation of water from frozen materials, preserving their structure and ensuring long-term stability for pharmaceuticals and food.3 Studies have investigated how techniques like vacuum-induced surface freezing can improve the efficiency and outcome of this process by controlling ice crystal formation.19

Beyond water, research on “soft matter” (e.g., foams, gels, and liquid crystals) in space environments is providing new insights.21 By removing the interference of gravity, scientists can study the intrinsic behavior and stability of these materials, leading to improvements in everything from firefighting foams to consumer products.21 Another intriguing avenue of research is the study of ionic liquids, salts that remain in a liquid state at low temperatures and pressures.22 Experiments have shown that these fluids can form from common planetary ingredients in vacuum conditions, broadening the search for potentially habitable environments on other planets.22

IV. Theoretical and Computational Models

To understand the full spectrum of liquid behavior in a vacuum, researchers have developed a range of theoretical and computational models that bridge the gap between macroscopic observations and microscopic phenomena.

A. Macroscopic Thermodynamic Models

Macroscopic models, such as various equations of state (e.g., Peng-Robinson) and activity coefficient models (e.g., NRTL, UNIFAC), provide a foundation for predicting the thermodynamic properties of liquids and gases.23 The ideal gas law, for instance, is a simple approximation often used for the vapor phase at very low pressures.23 However, as the research shows, many systems—especially those involving polar molecules like water or complex mixtures—deviate significantly from ideal behavior, requiring more complex models to predict their properties accurately.23 Simplified models used for industrial processes like vacuum cooling often rely on empirical data to fit parameters, such as the mass transfer coefficient, to experimental results.24

B. Molecular Kinetic Theory: From Hertz-Knudsen to Schrage

For non-equilibrium processes, such as the rapid evaporation of a liquid into a vacuum, a more detailed, molecular-level approach is necessary. The Hertz-Knudsen equation is a foundational model that describes the rate of evaporation as proportional to the difference between the saturation vapor pressure and the ambient pressure.10 However, this model assumes zero mean velocity in the vapor and introduces an empirical “sticking coefficient” (αv) to account for the fact that not all molecules impinging on the surface will stick.25

A more advanced model, the Schrage relationships, improves on the Hertz-Knudsen equation by accounting for the macroscopic vapor motion that occurs during rapid evaporation and condensation.27 This makes it a more suitable model for systems with high driving forces, such as evaporation into a vacuum, and recent molecular dynamics simulations have validated its accuracy.27 Despite its physical basis, a key challenge in applying the Schrage model remains the determination of the mass accommodation coefficient, which is often found by fitting the model to experimental data.28 This reliance on empirical fitting highlights a fundamental gap in the theoretical understanding of the liquid-vapor interface.

C. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool for probing the microscopic behaviors that govern phase transitions. By simulating the interactions of individual molecules, researchers can study phenomena that are inaccessible to direct experimental observation, such as the dynamics at the liquid-vapor interface.29 These simulations have been used to validate kinetic theories, predict evaporation coefficients, and explore complex phase behaviors.29 The use of MD simulations to study the evaporation of a liquid slab into a vacuum, for instance, has demonstrated its ability to model both the liquid and vapor phases and has provided valuable insights into the velocity distribution of evaporated molecules.29 This capability to resolve phenomena at a microscopic scale is essential for developing physically-based, rather than purely empirical, models.

V. Conflicting Viewpoints, Debates, and Unresolved Problems

A. The Evaporation-Induced Freezing Paradox

While the observation of a liquid boiling and freezing simultaneously in a vacuum is well-established, there is a debate over its practical significance in certain applications. In the HVAC industry, for example, there is a discussion about whether pulling a vacuum “too quickly” can freeze moisture within a system, thereby slowing down the evacuation process.32 A key video demonstration showed that in a small, insulated container, rapid vacuum pulling can indeed cause water to freeze. However, the author of a related article argues that this is rarely an issue in real-world systems because heat from the surroundings will counteract the cooling effect, unless the ambient temperature is already very low.32 This debate underscores that the outcome of a vacuum process is a complex interplay between the rate of evaporative cooling and the rate of heat ingress from the environment. This situation parallels the long-debated “Mpemba effect,” where hot water can freeze faster than cold water, with proposed explanations involving differences in dissolved gases, convection, and evaporative cooling.33

B. The “Two-Liquid” Phase Transition of Water

A profound and ongoing debate in the study of condensed matter is the hypothesis that water exhibits a first-order phase transition between a high-density liquid (HDL) and a low-density liquid (LDL) in the metastable supercooled regime.30 This theory has been proposed to explain several of water’s anomalous properties. Recent molecular dynamics simulations have provided evidence for this liquid-liquid phase transition (LLPT) and have advanced a new theory proposing that the LLPT is coupled to a ferroelectric phase transition, which is governed by the orientation of molecular dipoles.30 This challenges earlier hypotheses that focused solely on local structural geometry to explain the phenomenon. Despite these advances, direct experimental verification of the LLPT remains challenging due to water’s strong tendency to crystallize at these low temperatures.30

C. Clarifying Conceptual Distinctions: Physics vs. Cosmology

The term “vacuum phase transition” is also used in a completely separate field of fundamental physics: cosmology. In this context, it refers to the hypothetical decay of the universe’s “false vacuum” to a lower-energy “true vacuum”.37 This concept is a matter of quantum field theory and has no direct relationship to the physical phase changes of matter in an evacuated chamber. The “cosmological constant problem,” which describes the massive discrepancy between the theoretical zero-point energy of the vacuum and its observed value, is a related unresolved question in fundamental physics.39 It is critical to distinguish between these two distinct uses of the terminology to avoid conflating the behavior of physical liquids in a vacuum with the theoretical properties of space-time itself.

VI. Current Gaps and Directions for Future Research

Despite significant progress, several key gaps and opportunities for future research remain.

A. Experimental and Measurement Challenges

A primary challenge lies in the difficulty of obtaining precise measurements in dynamic vacuum environments. For example, while vacuum-induced surface freezing is a recognized phenomenon, the exact temperature gradients and freezing rates have yet to be accurately measured.40 The complexity of real-world systems, where variables such as ambient temperature, heat transfer from the container, and the presence of non-condensable gases can alter the outcome, highlights the need for more comprehensive, multi-variable studies that can be used to build and validate more robust models.32

B. Bridging Theory and Practice

A persistent gap exists between sophisticated theoretical models and their practical application in engineering simulations. The Schrage relationships, while a major improvement over simpler models, still rely on a mass accommodation coefficient that is often an empirically-derived fitting parameter.28 Future research should focus on using molecular dynamics simulations to theoretically determine this and other key parameters, providing a more physically-based foundation for models used in large-scale simulations. This would enable the design of more efficient industrial processes, such as vacuum-based cooling and composites manufacturing, without relying on extensive, costly experimental trial-and-error.5

C. The Role of Quantum Effects and Novel Fluids

Emerging research into the nature of vacuum itself suggests promising new directions. According to quantum field theory, a vacuum is not truly empty but is a sea of spontaneous energy fluctuations.21 The field of quantum thermodynamics is exploring whether it is possible to locally extract energy from this “zero-point energy,” a concept that could have profound implications for our understanding of matter at the quantum-mechanical level.41 Furthermore, the discovery that “ionic liquids” can form and remain stable in low-pressure, high-temperature environments opens up an entirely new avenue of research into fluid behavior beyond conventional water and hydrocarbons, with potential applications in astrobiology and materials science.22

VII. Conclusion

The study of liquid phase transitions in vacuum is a compelling field at the intersection of fundamental physics and applied engineering. A review of the literature reveals a clear progression from early, qualitative observations of boiling point depression and self-cooling to contemporary, high-precision studies of dynamic systems like flash evaporation. This evolution has been driven by a continuous feedback loop between experimental findings and the development of increasingly sophisticated theoretical and computational models.

While foundational principles are well-established, significant debates and unresolved problems persist. The paradox of simultaneous boiling and freezing, the proposed liquid-liquid phase transition in water, and the need for more accurate, predictive models highlight the areas where future research is most needed. By addressing the challenges of experimental measurement, bridging the gap between theory and application, and exploring the behavior of novel fluids and the quantum nature of the vacuum, the field is poised to yield new insights that will not only advance our fundamental understanding of matter but also lead to transformative innovations in industries ranging from space exploration to medicine.

Table I: Key Experimental Studies on Liquid-Vacuum Phase Transitions

| Study (Author, Year) | Liquid(s) Studied | Experimental Setup | Key Findings |

| Merget, 1872 11 | Frozen mercury | Vacuum apparatus | Perceptible volatilization in air; early evidence of sublimation. |

| Demarçay, 1882 11 | Cadmium, zinc, lead, tin | Vacuum apparatus | Found metals evaporated sensibly at temperatures well below melting points in vacuo. |

| Kaye & Ewen, 1913 12 | Various metals (iridium, copper, iron) | Heated strips in evacuated vessel | Distinguished between ordinary vapor and “rectilinear particles” that propagate in straight lines. |

| Luo et al.14 | Water, volatile liquids | Flash chamber with visualization windows | Superheat degree is the most important parameter influencing liquid jet breakup and atomization. |

| Mutair & Ikegami, 2010, 2012 16 | Superheated water jets | Experimental flash evaporation setup | Identified a “potential core zone” with no phase change; found that flow within large droplets increases thermal conductivity. |

| Satoh et al., 2023 18 | Superfluid helium | Magnetic trapping in a high vacuum cryostat | Successfully trapped millimeter-scale drops; observed evaporative cooling to 330 mK. |

Table II: Comparison of Kinetic Theory Models for Evaporation

| Model | Key Assumption(s) | Key Parameter(s) | Applicability/Limitations |

| Hertz-Knudsen Equation 25 | Assumes zero mean vapor velocity in the system. Evaporation rate is proportional to pressure difference. | Mass accommodation coefficient (α), vapor pressure (P∗). | Simple and foundational. Not accurate for high-rate evaporation into vacuum where vapor velocity is significant. |

| Schrage Relationships 27 | Accounts for the effects of macroscopic vapor motion. | Mass accommodation coefficient (α), liquid temperature (TL), vapor temperature (Tv). | More accurate for high-driving-force, non-equilibrium conditions. Still requires an empirically determined value for α. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations 29 | Models fluid at the molecular level with inter-particle potentials. | Inter-particle potential (e.g., Lennard-Jones), temperature gradients. | Capable of resolving the interface and deriving parameters like α from first principles. Computationally expensive and complex. |

Works cited

- Experiment #4: Water phase change in a vacuum chamber – YouTube, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ti9C_cLSR0A

- Boiling/Freezing of Water in a Vacuum | Harvard Natural Sciences Lecture Demonstrations, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://sciencedemonstrations.fas.harvard.edu/presentations/boilingfreezing-water-vacuum

- A review of water sublimation cooling and water evaporation cooling in complex space environments | Request PDF – ResearchGate, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/371797157_A_review_of_water_sublimation_cooling_and_water_evaporation_cooling_in_complex_space_environments

- How Does Applying A Vacuum Lower The Boiling Point Of A …, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://kindle-tech.com/faqs/how-would-vacuum-affect-the-boiling-point-of-a-compound

- Troubleshooting Vacuum Infusion – Explore Composites!, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://explorecomposites.com/articles/lamination/troubleshooting-vacuum-infusion/

- Vapor Pressure – Boiling Water Without Heat, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://chem.rutgers.edu/cldf-demos/1067-cldf-demo-vapor-pressure-boiling-water-without-heat

- High Altitude Cooking – USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.fsis.usda.gov/food-safety/safe-food-handling-and-preparation/food-safety-basics/high-altitude-cooking

- 2.3 Phase diagrams – Introduction to Engineering Thermodynamics, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/thermo1/chapter/phase-diagrams/

- Water Freezing Under a Good Vacuum | Physics Van | Illinois, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://van.physics.illinois.edu/ask/listing/1597

- SUBLIMATION – Thermopedia, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.thermopedia.com/cn/content/1163/

- The sublimation of metals at low pressures | Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspa.1913.0063

- The sublimation of metals at low pressures, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rspa.1913.0063

- Why does liquid nitrogen freeze when placed in a vacuum? : r/askscience – Reddit, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/askscience/comments/pwntn/why_does_liquid_nitrogen_freeze_when_placed_in_a/

- Investigation on the dispersal characteristics of … – UCL Discovery, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1519773/1/Luo-K_Investigation%20on%20the%20dispersal%20characteristics%20of%20liquid%20breakup%20in%20vacuum-final.pdf

- Characterization of Flashing Phenomena with Cryogenic Fluid …, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303529320_Characterization_of_Flashing_Phenomena_with_Cryogenic_Fluid_Under_Vacuum_Conditions

- On the evaporation of superheated water drops formed by flashing …, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257513645_On_the_evaporation_of_superheated_water_drops_formed_by_flashing_of_liquid_jets

- (PDF) Injection of high-speed cryogenic liquid jets in a vacuum, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343288910_Injection_of_high-speed_cryogenic_liquid_jets_in_a_vacuum

- Superfluid Helium Drops Levitated in High Vacuum | Phys. Rev. Lett., accessed on September 7, 2025, https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.130.216001

- Freeze-drying using vacuum-induced surface freezing – PubMed, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11835203/

- Vacuum-Induced Surface Freezing for the Freeze-Drying of the Human Growth Hormone: How Does Nucleation Control Affect Protein Stability? – ResearchGate, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332469474_Vacuum-Induced_Surface_Freezing_for_the_Freeze-Drying_of_the_Human_Growth_Hormone_How_Does_Nucleation_Control_Affect_Protein_Stability

- Why Does NASA Study Soft Matter in Space?, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://science.nasa.gov/biological-physical/why-does-nasa-study-soft-matter-in-space/

- Planets without water could still produce certain liquids, a new study finds | MIT News, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://news.mit.edu/2025/planets-without-water-could-still-produce-certain-liquids-0811

- Thermodynamic Models & Physical Properties – JUST, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.just.edu.jo/~yahussain/files/thermodynamic%20models.pdf

- (PDF) Mathematical model of the vacuum cooling of liquids, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/223368009_Mathematical_model_of_the_vacuum_cooling_of_liquids

- EE-527: MicroFabrication – MMRC, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://mmrc.caltech.edu/PVD/manuals/PhysicalVaporDeposition.pdf

- Hertz–Knudsen equation – Wikipedia, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hertz%E2%80%93Knudsen_equation

- Molecular simulation of steady-state evaporation and condensation in the presence of a non-condensable gas | The Journal of Chemical Physics | AIP Publishing, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jcp/article/148/6/064708/196439/Molecular-simulation-of-steady-state-evaporation

- Review of computational studies on boiling and condensation – Purdue College of Engineering, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://engineering.purdue.edu/mudawar/files/articles-all/2017/2017-05.pdf

- Mean field kinetic theory description of evaporation of a fluid into vacuum – ResearchGate, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/252989141_Mean_field_kinetic_theory_description_of_evaporation_of_a_fluid_into_vacuum

- The interplay between liquid–liquid and ferroelectric phase transitions in supercooled water, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2412456121

- Mass and heat transfer between evaporation and condensation surfaces: Atomistic simulation and solution of Boltzmann kinetic equation | PNAS, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1714503115

- Can Pulling a Vacuum too Fast Freeze Water/Moisture? – HVAC …, accessed on September 7, 2025, http://www.hvacrschool.com/can-pulling-vacuum-fast-freeze-water-moisture/

- Paradox of temperature decreasing without unique explanation – PMC, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4843881/

- Aristotle-Mpemba effect – EoHT.info, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.eoht.info/page/Aristotle-Mpemba%20effect

- Mpemba effect – Wikipedia, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mpemba_effect

- Melting Temperature Hidden Behind Liquid–Liquid Phase Transition in Glycerol | The Journal of Physical Chemistry B – ACS Publications, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpcb.4c04552

- Vacuum Decay: Expert Survey Results – Effective Altruism Forum, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/CFv82Xt2kuvvjNvP8/vacuum-decay-expert-survey-results-1

- False vacuum – Wikipedia, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/False_vacuum

- Vacuum energy – Wikipedia, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vacuum_energy

- Vacuum-Induced Surface Freezing to Produce Monoliths of Aligned Porous Alumina – MDPI, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/9/12/983

- Researchers bring theory to reality with a new experiment | Science | University of Waterloo, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://uwaterloo.ca/science/news/researchers-bring-theory-reality-new-experiment

One response to “Vacuum-Induced Phase Changes in Liquids: A Comprehensive Review of Thermodynamic Behavior and Experimental Studies”

[…] Precise physical conditions under which the Navier-Stokes equations’ underlying assumptions br… […]

LikeLike