Circular Astronomy

Twitter List – See all the findings and discussions in one place

-

The Mysterious Discovery of JWST That No One Saw Coming

Are We Inside a Cosmic Whirlpool? Recent JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES) observations of mysterious cosmological anomalies in the rotational patterns of galaxies challenge our understanding of the universe and reveal surprising connections to natural growth patterns.

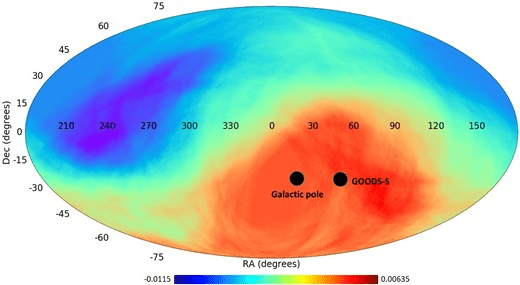

The rotation of 263 galaxies has been studied by Lior Shamir of Kansas State University, with 158 rotating clockwise and 105 rotating counterclockwise. The number of galaxies rotating in the opposite direction relative to the Milky Way is approximately 1.5 times higher than those rotating in the same direction.

New Cosmological anomalies that challenge our cosmological models and would have angered Einstein.

This observation challenges the expectation of a random distribution of galaxy rotation directions in the universe based on the isotropy assumption of the Cosmological Principle.

This is certainly not something Einstein would have liked to hear during his lifetime, but it would have excited Johannes Kepler.

What does this mean for our cosmological models, and why would it make Johannes Kepler happy?

The 1.5 ratio in galaxy rotation bias is intriguingly close to the Golden Ratio of 1.618. The Golden Ratio was one of Johannes Kepler’s two favorites. The astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) referred to the Golden Ratio as one of the “two great treasures of geometry” (the other being the Pythagorean theorem). He noted its connection to the Fibonacci sequence and its frequent appearance in nature.

What is the Fibonacci sequence?

The Italian mathematician Leonardo of Pisa, better known as Fibonacci, introduced the world to a fascinating sequence in his 1202 book Liber Abaci (The Book of Calculation). This sequence, now famously known as the Fibonacci sequence, was presented through a hypothetical problem involving the growth of a rabbit population.

The growth of a rabbit population and why it matters?

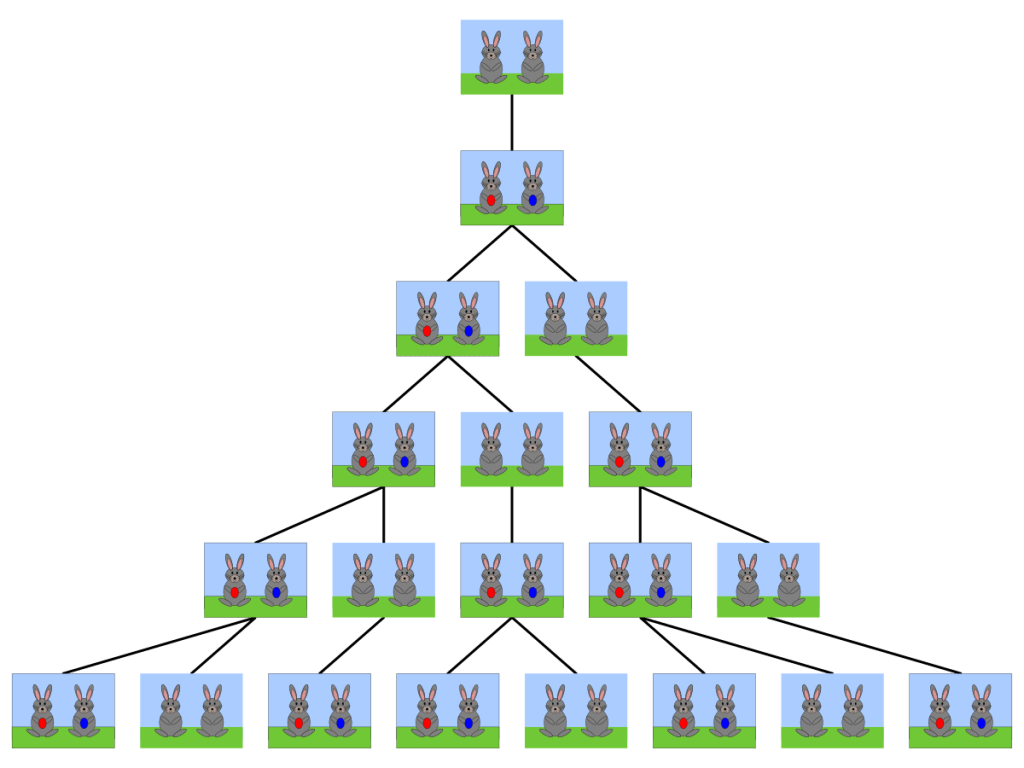

Fibonacci posed the following question: Suppose a pair of rabbits can reproduce every month starting from their second month of life. If each pair produces one new pair every month, how many pairs of rabbits will there be after a year?

The solution unfolds as follows:

- In the first month, there is 1 pair of rabbits.

- In the second month, there is still 1 pair (not yet reproducing).

- In the third month, the original pair reproduces, resulting in 2 pairs.

- In the fourth month, the original pair reproduces again, and the first offspring matures and reproduces, resulting in 3 pairs.

Image Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FibonacciRabbit.svg

This pattern continues, with each new generation adding to the total, where each term is the sum of the two preceding terms.

The Fibonacci sequence generated is: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, …

While this idealized model of a rabbit population assumes perfect conditions—no sickness, death, or other factors limiting reproduction—it reveals a growth pattern that approaches the Golden Ratio as the sequence progresses. The ratio is determined by dividing the current population by the previous population. For example, if the current population is 55 and the previous population is 34, based on the Fibonacci sequence above, the ratio of 55/34 is approximately 1.618.

However, in reality, the growth rate of a rabbit population would likely fall below this mathematical ideal ratio due to natural constraints.Yet, this growth (evolutionary) pattern appears quite often in nature, such as in the growth patterns of succulents.

The growth patterns in succulents often follow the Fibonacci sequence, as seen in the arrangement of their leaves, which spiral around the stem in a way that maximizes sunlight exposure. This spiral phyllotaxis reflects Fibonacci numbers, where the number of spirals in each direction typically corresponds to consecutive terms in the sequence.

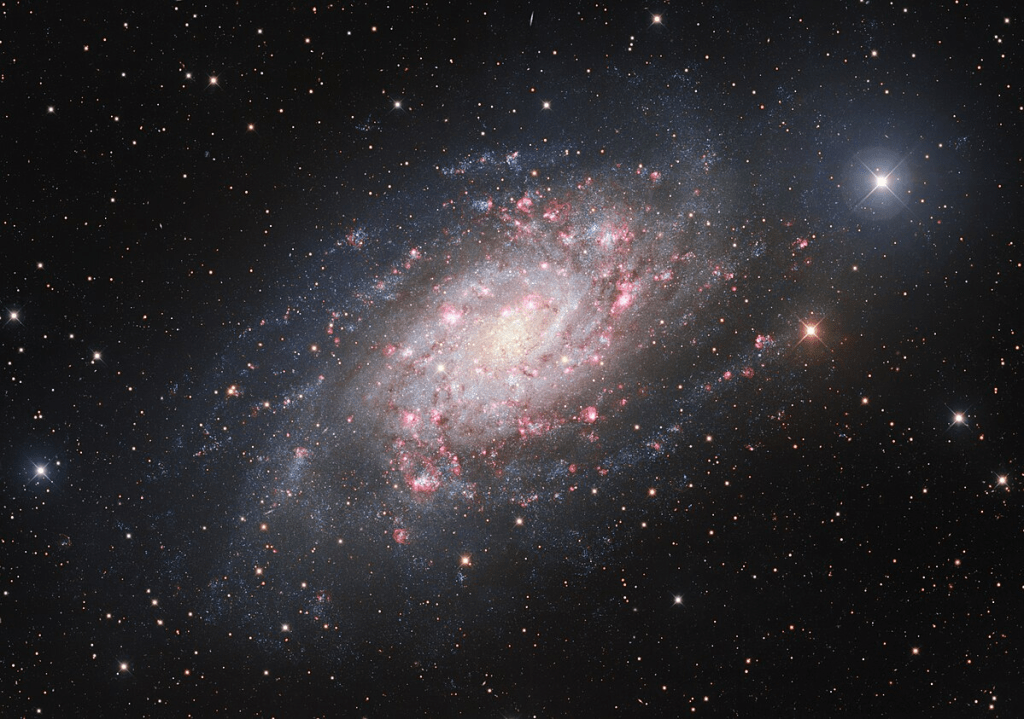

Spiral galaxies exhibit a similar growth (evolutionary) pattern in their spiral arms.

Spiral galaxies, like the Milky Way, display strikingly similar growth patterns in their spiral arms, where new stars are continuously formed and not in the center of the galaxy.

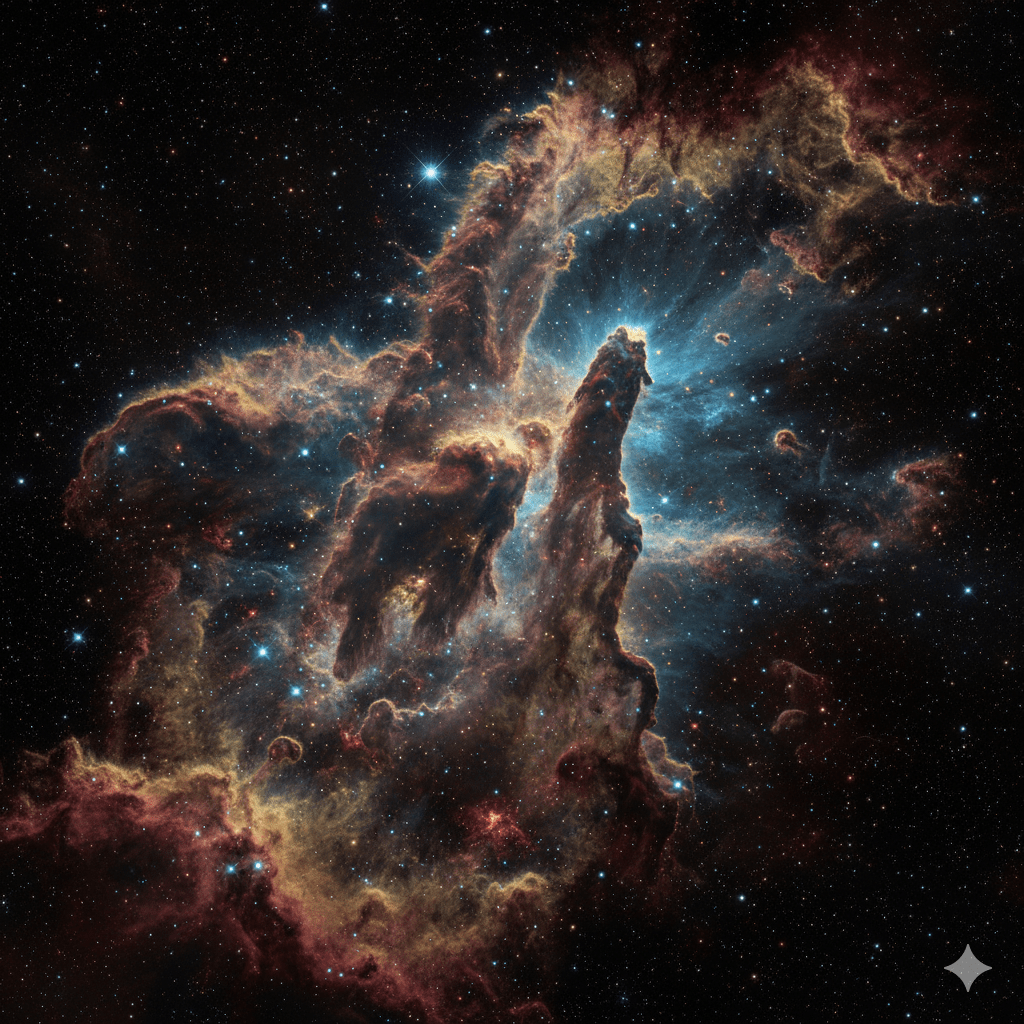

Image Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_Galaxy_of_Birth_and_Death.jpg

Returning to the observations and research conducted by Lior Shamir of Kansas State University using the JWST.

The most galaxies with clockwise rotation are the furthest away from us.

The GOODS-S field is at a part of the sky with a higher number of galaxies rotating clockwise

Image Source: Figure 10 https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staf292

“If that trend continues into the higher redshift ranges, it can also explain the higher asymmetry in the much higher redshift of the galaxies imaged by JWST. Previous observations using Earth-based telescopes e.g., Sloan Digital Sky Survey, Dark Energy Survey) and space-based telescopes (e.g., HST) also showed that the magnitude of the asymmetry increases as the redshift gets higher (Shamir 2020d).” Source: [1]“It becomes more significant at higher redshifts, suggesting a possible link to the structure of the early universe or the physics of galaxy rotation.” Source: [1]

Could the universe itself be following the same growth patterns we see in nature and spiral galaxies?

This new observation by Lior Shamir is particularly intriguing because, if we were to shift the perspective of our standard cosmological model—from one based on a singularity (the Big Bang ‘explosion’), which is currently facing a lot of challenges [2], to a growth (evolutionary) model—we would no longer be observing the early universe. Instead, we would be witnessing the formation of new galaxies in the far distance, presenting a perspective that is the complete opposite of our current worldview (paradigm).

NEW: Massive quiescent galaxy at zspec = 7.29 ± 0.01, just ∼700 Myr after the “big bang” found.

RUBIES-UDS-QG-z7 galaxy is near celestial equator.

It is considered to be a “massive quiescent galaxy’ (MQG).

These galaxies are typically characterized by the cessation of their star formation.

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/adab7a

The rotation, whether clockwise or counterclockwise, has not yet been observed.Reference

The distribution of galaxy rotation in JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey

Lior Shamir

[1 ] https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/538/1/76/8019798?login=false

The Hubble Tension in Our Own Backyard: DESI and the Nearness of the Coma Cluster

Daniel Scolnic, Adam G. Riess, Yukei S. Murakami, Erik R. Peterson, Dillon Brout, Maria Acevedo, Bastien Carreres, David O. Jones, Khaled Said, Cullan Howlett, and Gagandeep S. Anand

[2] https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2041-8213/ada0bd

Reading Recommendation:

The Golden Ratio, Mario Livio, 2002

Mario Livio was an astrophysicist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, which operates the Hubble Space Telescope.

RUBIES Reveals a Massive Quiescent Galaxy at z = 7.3

Andrea Weibel, Anna de Graaff, David J. Setton, Tim B. Miller, Pascal A. Oesch, Gabriel Brammer, Claudia D. P. Lagos, Katherine E. Whitaker, Christina C. Williams, Josephine F.W. Baggen, Rachel Bezanson, Leindert A. Boogaard, Nikko J. Cleri, Jenny E. Greene, Michaela Hirschmann, Raphael E. Hviding, Adarsh Kuruvanthodi, Ivo Labbé, Joel Leja, Michael V. Maseda, Jorryt Matthee, Ian McConachie, Rohan P. Naidu, Guido Roberts-Borsani, Daniel Schaerer, Katherine A. Suess, Francesco Valentino, Pieter van Dokkum, and Bingjie Wang (王冰洁)

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/adab7a

Appendix Spiral Galaxies:

Spiral galaxies are known for their stunning and symmetrical spiral arms, and many of them exhibit patterns that approximate logarithmic spirals, which are mathematically related to the Golden Ratio. While not all spiral galaxies perfectly follow the Golden Ratio, some exhibit spiral arm structures that closely resemble this pattern. Here are some notable examples of spiral galaxies with logarithmic spiral patterns:

1. Milky Way Galaxy

- Our own galaxy, the Milky Way, is a barred spiral galaxy with arms that approximate logarithmic spirals. The four primary spiral arms (Perseus, Sagittarius, Scutum-Centaurus, and Norma) follow a logarithmic pattern, though not perfectly aligned with the Golden Ratio.

2. M51 (Whirlpool Galaxy)

- The Whirlpool Galaxy is one of the most famous examples of a spiral galaxy with well-defined logarithmic spiral arms. Its arms are nearly symmetrical and exhibit a pattern that closely resembles the Golden Ratio.

3. M101 (Pinwheel Galaxy)

- The Pinwheel Galaxy is a grand-design spiral galaxy with prominent and well-defined spiral arms. Its structure is often cited as an example of a logarithmic spiral in astronomy.

4. NGC 1300

- NGC 1300 is a barred spiral galaxy with a striking logarithmic spiral pattern in its arms. It is often studied for its near-perfect spiral structure.

5. M74 (Phantom Galaxy)

- The Phantom Galaxy is another grand-design spiral galaxy with arms that follow a logarithmic spiral pattern. Its symmetry and structure make it a textbook example of this phenomenon.

6. NGC 1365

- Known as the Great Barred Spiral Galaxy, NGC 1365 has a prominent bar structure and spiral arms that exhibit a logarithmic pattern.

7. M81 (Bode’s Galaxy)

- Bode’s Galaxy is a spiral galaxy with arms that follow a logarithmic spiral structure. It is one of the brightest galaxies visible from Earth and a popular target for astronomers.

8. NGC 2997

- This galaxy is a grand-design spiral galaxy with arms that closely resemble logarithmic spirals. It is located in the constellation Antlia.

9. NGC 4622

- Known as the “Backward Galaxy,” NGC 4622 has a unique spiral structure with arms that follow a logarithmic pattern, though its rotation direction is unusual.

10. M33 (Triangulum Galaxy)

- The Triangulum Galaxy is a smaller spiral galaxy with arms that exhibit a logarithmic spiral structure. It is part of the Local Group, along with the Milky Way and Andromeda.

-

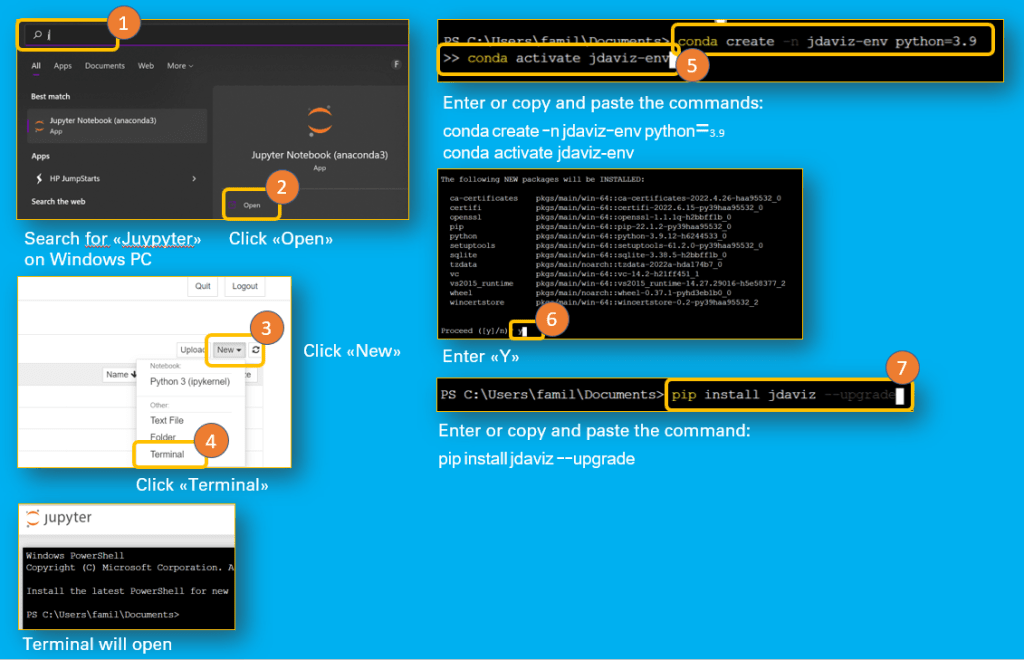

How to Download, View, And Edit Images from the James Webb Space Telescope with Jdaviz and Imviz

Like to comfortably view and edit images from the Jamew Webb Space Telescope like an astronomer ?

Then follow this step by step cheatsheet guides if you are using windows on a PC .

Main Software Components

There are three key software components required:

- Microsoft C++ 14

- Jupyter Notebook (Python)

- Jdaviz

Additonal

- MAST Token to be able to download the images with Imviz.

Prerequsites:

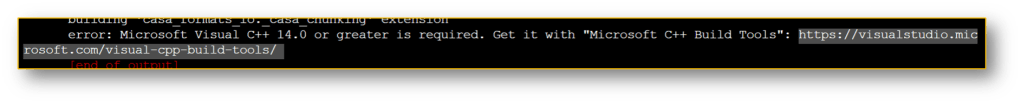

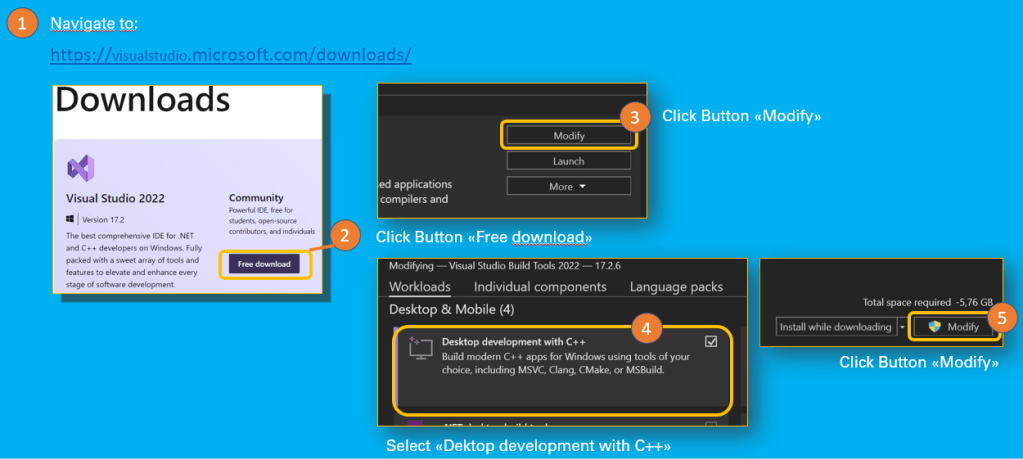

Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater

error: Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater is required If Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater is not installed, the installation of Jdaviz will fail. Without Jdaviz the downloaded images from the James Webb Space Telescope cannot be edited.

How to install Microsoft Visual C++

- Navigate to: https://visualstudio.microsoft.com/downloads/

- Download Visual Studio 2022 Community version

- Follow the instructions in this post: Install C and C++ support in Visual Studio | Microsoft Docs

Cheatsheet: Install Visual Studio 2022 MAST Token

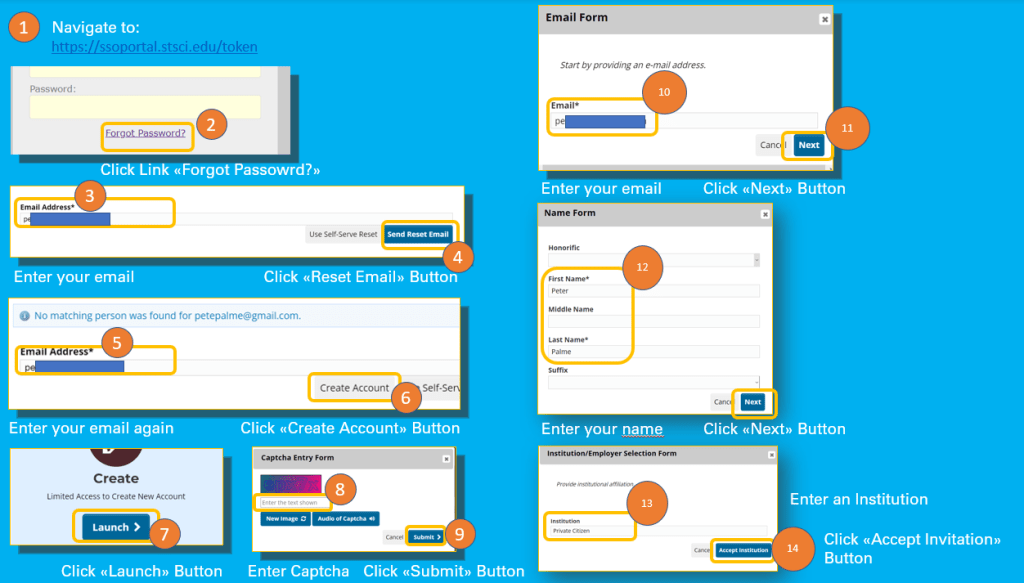

- Navigate to https://ssoportal.stsci.edu/token

If you do not have not an account yet, please follow below steps to create your account:

- Click on the Forgotten Password? link

- Enter your email Adress

- Click Send Reset Email Button

- Click Create Account Button

- Click Launch Button

- Enter the Captcha

- Click Submit Button

- Enter your email

- Click Next Button

- Fill in the Name Form

- Click Next Button

- Fill in the Insitution (e.g. Private Citizen or Citizen Scientist)

- Click Accept Institution Button

- Enter Job Title (whatever you are or like to be ;-))

- Click Next Button

- New Account Data for your review is presented, in case of missing contact data, step 17 might be necessary

- Fill in Contact Information Form

- Click Next Button

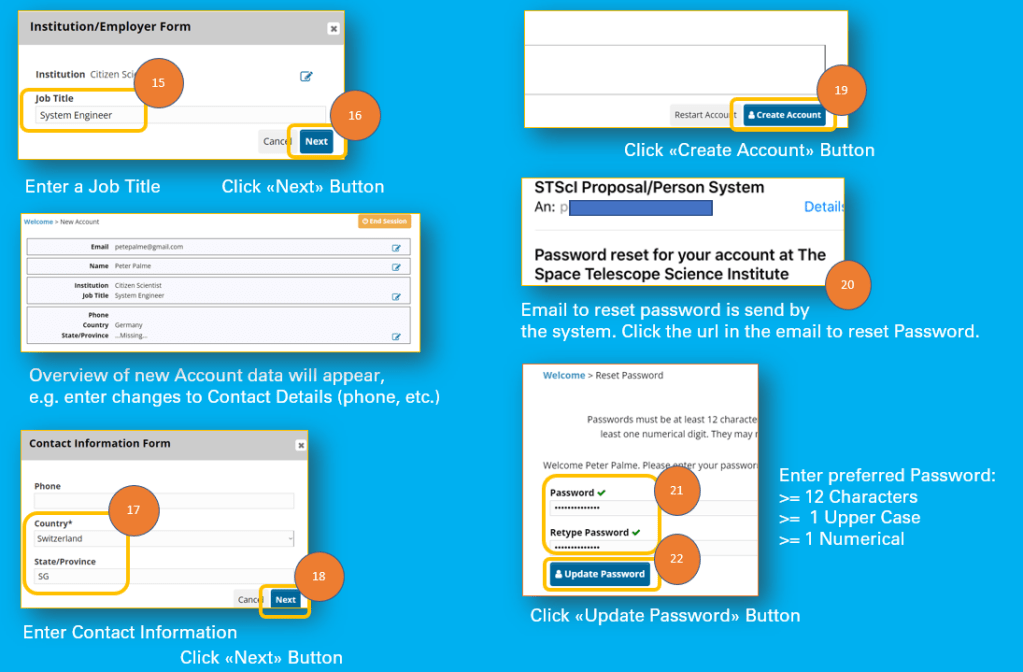

- Click Create Account Button

- In your email account open the reset password emal

- Click on the link

- Enter Password

- Enter Retype Password

- Click Update Password

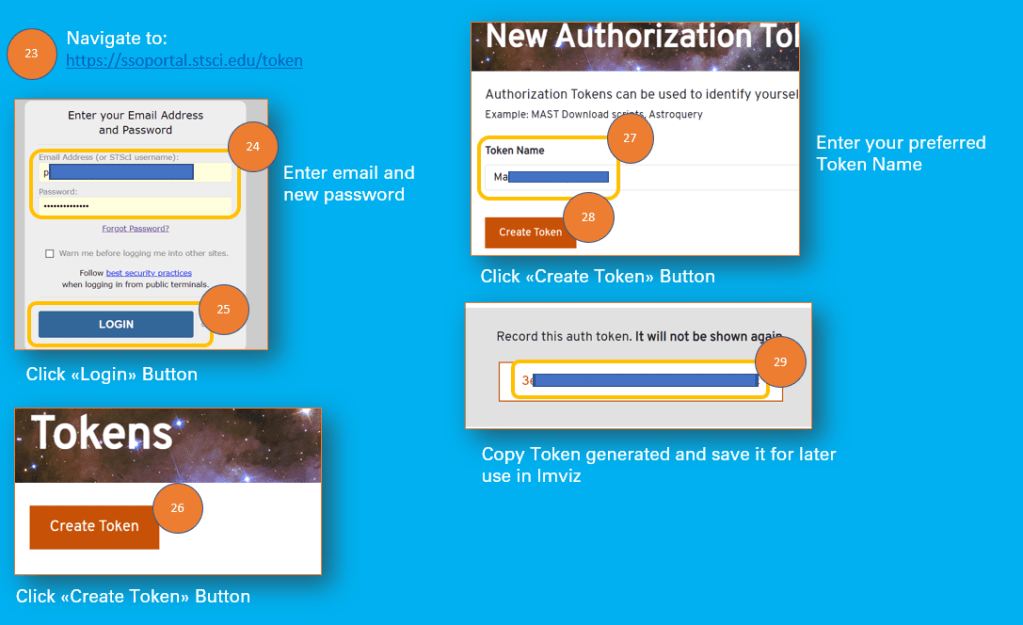

- Navigate to https://ssoportal.stsci.edu/token

- Now log on with your email and new account password

- Click Create Token Button

- Fill in a Token Name of your choice

- Click Create Token Button

- Copy the Token Number and save it for later use in Imviz to download the images from the James Webb Space Telescope

Quite a lot of steps for a Token.

Cheatsheet: Create MAST Account

Cheatsheet: Set Passord for new Account

Cheatsheet: Create MAST Token for use in Imviz Jupyter Notebook

Jupyter notebook comes with the ananconda distribution.

- Navigate to: https://www.anaconda.com/products/distribution#windows

- Follow the instructions at: https://docs.anaconda.com/anaconda/install/windows/

Install Jdaviz

- Navigate to: Installation — jdaviz v2.7.2.dev6+gd24f8239

- Open the Jupyter Notebook

- Open Terminal from Jupyter Notebook

- Follow the instruction in: Installation — jdaviz v2.7.2.dev6+gd24f8239

Cheatsheet: Install Jdaviz How to use IMVIZ

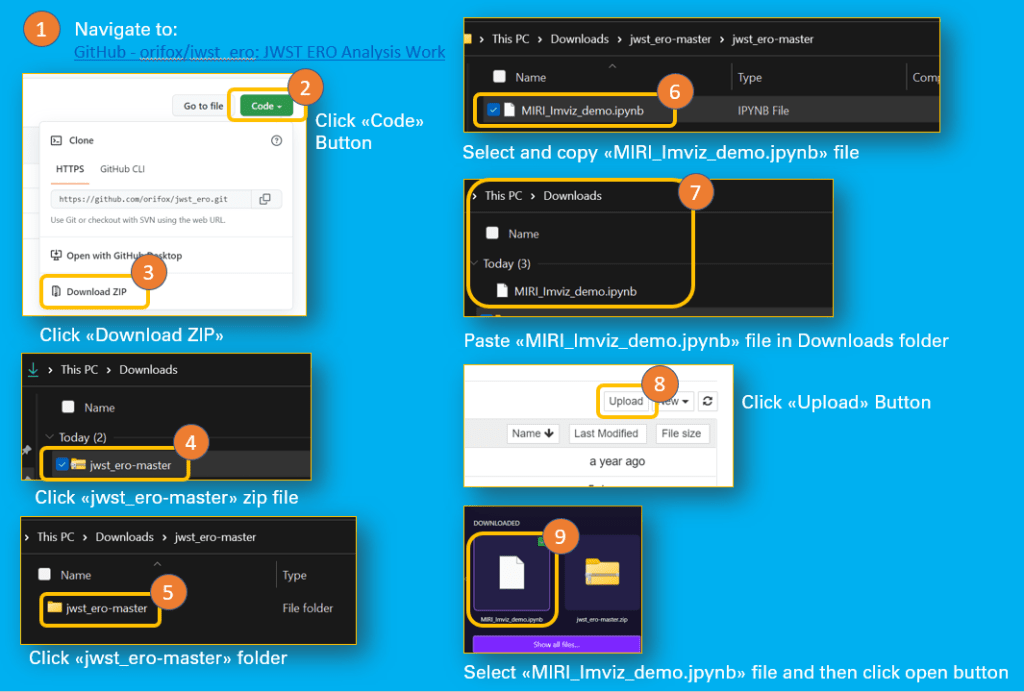

Imviz is installed together with Jdaviz.

Following steps to take in order to use Imviz:

- Navigate to: GitHub – orifox/jwst_ero: JWST ERO Analysis Work

- Click Code Button

- Click Download Zip

- If you do not have unzip, then the next steps might work for you:

- In Download Folder (PC) click the jwst_ero master zip file

- Then click on the folder jwst_ero master

- Copy file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb

- Paste the file in the download folder

- Open Jupyter notebook

- Click Upload Button

- Select the file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb

- Click Open Button

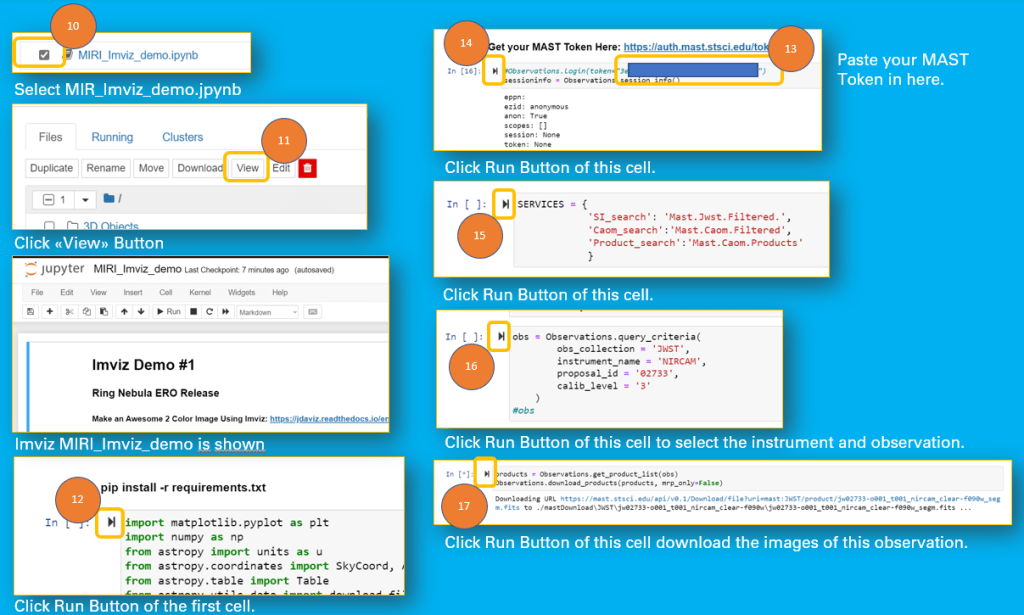

- Select the file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb in the Jupyter Notebook file list

- Click View Button

- Click Run Button First Cell

- Paste MAST Token in next cell

- Click Run Button of this Cell

- Click then Run Button of next Cell

- Click Run Button of the following Cell

- Click Run Button of the next Cell to download the images

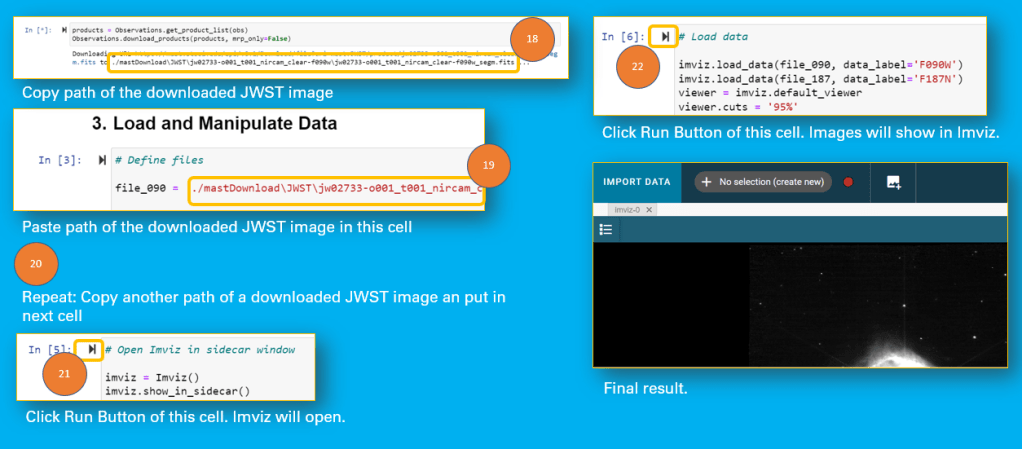

- Copy the link to the downloaded image file

- Past link into the First Cell in 3. Load and Manipulate Data

- Do the same in the next Cell

- Click Run Button of the Cell to open Imviz

- Click Run Button on the next Cell to load images in Imviz

Cheatsheet: Upload MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb in Jupyter notebook Now all set to download the images of the JWST observation:

Cheatsheet: Download JWST images with Imviz And now all is set to open and edit the images in Imviz

Cheatsheet: Open Images in Imviz And finally you are ready to follow the video tutorials in order to learn how to use Imviz to manipulate the JWST images.

Video Tutorials for Imviz:

And this is the master Ori Fox of the Imviz demo notebook file if you like to follow him on Twitter

-

Time for a new scientific debate – Accretion vs Convection

To what degree is gravity needed to form structures in space? While many believe that celestial bodies (stars, planets, moons, meteoroids) can only form through gravitational attraction in the vacuum of space, I believe that these bodies form through a thermodynamic process similar to the formation of hydrometeors (e.g., hail). This is because our solar system possesses a boundary layer, a discovery made by the Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) mission in 2013.

In simple terms: Planets, moons, and small bodies are formed within convection cells created by the jet streams of a young sun, under the influence of strong magnetic fields.

Recently, a new paper introduced quantum models in which gravity emerges from the behavior of qubits or oscillators interacting with a heat bath.

More details and link to the research paper: On the Quantum Mechanics of Entropic Forces

https://circularastronomy.com/2025/10/09/entropic-gravity-explained-how-quantum-thermodynamics-could-replace-gravitons/ -

Unraveling the Cosmic Dipole Anomaly: A Comprehensive Literature Review of Challenges to the Cosmological Principle

1. Introduction: The Foundational Assumptions of Modern Cosmology

The standard model of cosmology, known as , stands as one of the triumphs of twentieth-century physics. It successfully integrates the expansion of the Universe, the synthesis of light elements, the formation of large-scale structure, and the existence of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) into a coherent narrative. However, this model rests upon a foundational axiom that precedes the field equations of General Relativity themselves: the Cosmological Principle (CP). The CP asserts that, on sufficiently large scales (typically exceeding 100 Mpc), the Universe is statistically homogeneous and isotropic. This implies that there are no privileged positions and no privileged directions in the cosmos.1

The mathematical manifestation of the CP is the Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) metric, which reduces the ten independent components of the Einstein field equations to differential equations governing a single time-dependent scale factor, . This metric underpins our definitions of cosmic time, the Hubble parameter , and the interpretation of redshift as a measure of expansion.1 Consequently, the validity of the model—and indeed, our understanding of dark energy, dark matter, and the age of the Universe—is inextricably linked to the validity of the FLRW metric and the CP.

While the CP was initially a philosophical necessity—introduced by Einstein and later formalized by Milne to make the equations of cosmology solvable—it has since been subjected to rigorous observational testing. The discovery of the CMB in 1965 provided strong evidence for isotropy, revealing a Universe that was remarkably uniform in its infancy. The temperature fluctuations in the CMB, , are on the order of , consistent with a Universe that is isotropic to a high degree of precision.3

However, the CMB is not perfectly isotropic. It contains a prominent dipole anisotropy, a variation in temperature of amplitude , which is two orders of magnitude larger than the primordial fluctuations. In the standard paradigm, this dipole is interpreted not as an intrinsic feature of the Universe, but as a kinematic effect arising from the peculiar motion of the Solar System relative to the cosmic rest frame.4 This interpretation predicts that a corresponding dipole must exist in the distribution of distant extragalactic sources. If the Solar System is moving through a sea of photons, it is also moving through the sea of galaxies and quasars that constitute the large-scale structure (LSS) of the Universe.

Over the past two decades, and intensifying in recent years with the release of large-area surveys like CatWISE and RACS, a significant tension has emerged. Measurements of the dipole in the number counts of distant radio galaxies and quasars consistently reveal an amplitude that is significantly larger—by a factor of two to three—than the kinematic prediction derived from the CMB.3 This discrepancy, now reaching statistical significance levels exceeding , has been termed the “Cosmic Dipole Anomaly.” It represents one of the most severe challenges to the CP and the standard model, suggesting that the rest frame of matter and the rest frame of radiation may not coincide, or that the Universe possesses an intrinsic anisotropy that violates the fundamental assumptions of FLRW cosmology.1

This report provides an exhaustive review of the Cosmic Dipole Anomaly. It synthesizes evidence from radio continuum surveys, infrared quasar catalogs, and redshift tomography. It examines the theoretical basis for the kinematic dipole, the statistical methodologies used to measure it, and the potential for systematic errors. Furthermore, it explores theoretical extensions to the standard model—including “tilted” Bianchi cosmologies and modified gravity theories—that seek to explain the anomaly. Finally, it forecasts the potential of next-generation facilities such as the Euclid mission, the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), and the Vera C. Rubin Observatory (LSST) to definitively resolve this cosmic puzzle.

2. The Kinematic Hypothesis and the Cosmic Microwave Background

2.1 The CMB Dipole: Observation and Interpretation

The Cosmic Microwave Background provides the ultimate reference frame for cosmology. Observations by the COBE, WMAP, and Planck satellites have mapped the CMB temperature field with exquisite precision. The dominant feature in these maps, after the monopole temperature $T_0 = 2.7255$ K, is the dipole moment.

The Planck 2018 results constrain the solar system’s peculiar velocity, under the kinematic interpretation, to be:

$$v_{\text{CMB}} = 369.82 \pm 0.11 \text{ km s}^{-1}$$

This velocity vector points towards the Galactic coordinates $(l, b) = (264.021^\circ \pm 0.011^\circ, 48.253^\circ \pm 0.005^\circ)$.3

In the standard model, this velocity is attributed to the gravitational pull of local large-scale structures. The Solar System orbits the Galactic Center; the Milky Way falls towards the Andromeda Galaxy; the Local Group falls towards the Virgo Cluster; and the Local Supercluster is influenced by the Great Attractor and the Shapley Concentration.9 The vector sum of these motions results in the net velocity observed as the CMB dipole.

The temperature distribution of the CMB in the presence of an observer velocity $\vec{v}$ is given by the relativistic Doppler formula:

$$T(\hat{n}) = \frac{T_0}{\gamma (1 – \vec{\beta} \cdot \hat{n})}$$where $\vec{\beta} = \vec{v}/c$, $\gamma = (1 – \beta^2)^{-1/2}$ is the Lorentz factor, and $\hat{n}$ is the direction of observation. To first order in $\beta$, this simplifies to:

$$T(\hat{n}) \approx T_0 (1 + \hat{n} \cdot \vec{\beta})$$

This dipolar modulation is kinematic in nature. It is not an intrinsic variation in the temperature of the last scattering surface, but a frame-dependent effect. Crucially, this interpretation relies on the assumption that the CMB rest frame represents the global rest frame of the Universe. If the CP holds, the distribution of matter on large scales must also be isotropic in this same frame.4

2.2 Relativistic Effects on Matter Distribution

If the CMB dipole is kinematic, an observer moving with velocity $\vec{v}$ relative to the cosmic rest frame should see a specific signature in the distribution of distant sources. This signature arises from two distinct relativistic effects: Doppler boosting and relativistic aberration.1

2.2.1 Doppler Boosting

The flux density $S$ of a source is frame-dependent. For a source with a power-law spectrum $S \propto \nu^{-\alpha}$, the observed flux density $S_{\text{obs}}$ is related to the rest-frame flux density $S_{\text{rest}}$ by:

$$S_{\text{obs}} = S_{\text{rest}} \delta^{1+\alpha}$$

where $\delta = [\gamma (1 – \vec{\beta} \cdot \hat{n})]^{-1}$ is the Doppler factor. Since $\delta > 1$ in the direction of motion, sources appear brighter. In a flux-limited survey (which counts all sources brighter than a threshold $S_{\text{lim}}$), this brightening brings sources that would otherwise be too faint to be detected into the sample. The magnitude of this effect depends on the slope of the number counts, $x$, defined by $N(>S) \propto S^{-x}$.3

2.2.2 Relativistic Aberration

Aberration is the apparent displacement of objects toward the direction of motion. The angle of incidence $\theta$ in the observer’s frame is related to the angle $\theta’$ in the rest frame by:

$$\cos \theta = \frac{\cos \theta’ + \beta}{1 + \beta \cos \theta’}$$

This effect causes the solid angle elements to shrink in the forward direction and expand in the backward direction. Consequently, the number density of sources per unit solid angle increases in the direction of motion, even if the intrinsic spatial distribution is uniform.9

2.3 The Ellis-Baldwin Formulation

In their seminal 1984 paper, George Ellis and John Baldwin derived the combined effect of boosting and aberration on the observed number counts of sources. They showed that for a flux-limited survey of sources with spectral index $\alpha$ and count slope $x$, the observed number density $N(\hat{n})$ is modulated by a dipole of amplitude $\mathcal{D}$:

$$N(\hat{n}) = \bar{N} (1 + \mathcal{D} \cos \theta)$$where the theoretical kinematic dipole amplitude is:$$\mathcal{D}_{\text{kin}} = [2 + x(1 + \alpha)] \beta$$

The term “2” arises from aberration (and geometric dilution), while the term $x(1+\alpha)$ accounts for the Doppler boosting of flux across the survey threshold.3

This formula provides a rigorous consistency test for the standard model. Since $\beta$ is fixed by the CMB measurement ($\beta \approx 1.23 \times 10^{-3}$) and $x$ and $\alpha$ are observable properties of the galaxy population, one can predict $\mathcal{D}_{\text{kin}}$ precisely. For typical radio populations ($x \sim 1$, $\alpha \sim 0.75$), the amplification factor is roughly 4, leading to a predicted matter dipole of $\mathcal{D} \approx 0.5\%$. Any significant deviation from this prediction implies a violation of the underlying assumptions: either the velocity $\beta$ is different (implying matter and radiation frames differ), or the intrinsic universe is not isotropic.4

3. Observational Evidence from Radio Continuum Surveys

Radio galaxies have historically been the tracer of choice for testing the cosmic dipole. They are detectable out to high redshifts ($z \sim 1-2$), are sparse enough to avoid confusion, and are less affected by dust extinction than optical sources.

3.1 The NRAO VLA Sky Survey (NVSS)

The NVSS, conducted at 1.4 GHz with the Very Large Array, covers the entire sky north of declination $-40^\circ$. It contains nearly 2 million sources and has served as the primary dataset for dipole studies for two decades.3

Early studies, such as those by Blake and Wall (2002), detected a dipole in the NVSS number counts that was directionally consistent with the CMB. However, the amplitude was found to be somewhat larger than the kinematic prediction, though the large error bars at the time allowed for consistency. As measurement techniques refined, the tension grew. Singal (2011) performed a comprehensive analysis, applying stricter flux cuts to ensure completeness and removing local sources. This study found a dipole amplitude approximately four times larger than the CMB prediction, with a significance exceeding $3\sigma$.5

Subsequent re-analyses have largely confirmed this excess. Rubart and Schwarz (2013) and Tiwari et al. (2015) employed different estimators and masking strategies, consistently finding amplitudes in the range of $\mathcal{D} \sim 1.5 – 2.5 \times 10^{-2}$, compared to the expected $\sim 0.5 \times 10^{-2}$. The direction of the NVSS dipole generally aligns with the CMB dipole (within $\sim 20^\circ-30^\circ$), which is crucial; a random systematic error would not be expected to align with the Solar motion vector so well.5

3.2 The TIFR GMRT Sky Survey (TGSS)

The TGSS ADR1, operating at 150 MHz, offers a low-frequency counterpart to NVSS. Investigating the dipole at different frequencies is essential for checking frequency-dependent systematics. Analyses of TGSS data have reported even more extreme anomalies, with some studies finding dipole amplitudes up to ten times the kinematic expectation.5 However, TGSS is known to have more complex calibration issues and significant ionospheric effects compared to NVSS, leading some researchers to treat these extreme values with caution. Nevertheless, when conservative cuts are applied, TGSS still exhibits a statistically significant excess over the $\Lambda$CDM prediction.

3.3 The Rapid ASKAP Continuum Survey (RACS)

The arrival of the Rapid ASKAP Continuum Survey (RACS) has provided a vital new dataset in the Southern Hemisphere, complementing the Northern coverage of NVSS. RACS-low, centered at 887.5 MHz, covers the sky south of $\delta = +30^\circ$.

Recent studies combining NVSS and RACS provide a near-all-sky view of the radio continuum universe. Wagenveld et al. (2025) and Oayda et al. (2025) performed Bayesian analyses of the combined NVSS and RACS datasets. They found that while there are internal tensions between the catalogs (likely due to different flux scales and calibration strategies), the combined data strongly reject the purely kinematic CMB hypothesis. Specifically, RACS data alone indicates a “strong tension” with the Planck expectation, yielding a dipole amplitude consistent with the NVSS excess.3

3.4 Summary of Radio Dipole Findings

The consensus from radio surveys is clear: while the direction of the matter dipole is broadly consistent with the CMB dipole, the amplitude is persistently high. The inferred velocity of the Solar System relative to the radio galaxy frame is $v_{\text{radio}} \sim 1000 – 1500$ km s$^{-1}$, drastically higher than the $v_{\text{CMB}} \approx 370$ km s$^{-1}$. This “Radio Dipole Anomaly” suggests that radio galaxies are not at rest in the CMB frame, or that there is a surplus of sources in the direction of motion that cannot be explained by kinematics alone.9

4. The Quasar Dipole and the “Orthogonality” Argument

While radio surveys provided the first hints of the anomaly, they are susceptible to specific systematics, such as calibration drifts in interferometers and the complex morphology of radio lobes (which can be resolved into multiple sources, biasing counts). Quasars (Active Galactic Nuclei) observed in the infrared provide an independent and physically distinct tracer.

4.1 The Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) and CatWISE

The WISE mission mapped the entire sky in four infrared bands. The CatWISE2020 catalog, derived from WISE data, contains roughly 1.35 million quasars selected via their red mid-infrared colors ($W1 – W2 \ge 0.8$). This selection effectively isolates AGNs at redshifts $0.5 < z < 2.0$ (mean $z \sim 1.2$) from stars and normal galaxies.2

Secrest et al. (2021) performed a landmark analysis of the CatWISE quasar distribution. After masking the Galactic plane and correcting for extinction, they measured a dipole with an amplitude of $\mathcal{D}_{\text{obs}} = 0.01554 \pm 0.00079$. The kinematic expectation, derived from the specific $x$ and $\alpha$ of the quasar population, was $\mathcal{D}_{\text{kin}} \approx 0.007$.

- Significance: The observed dipole is more than double the expected value. The statistical significance of the discrepancy is $4.9\sigma$ (one-sided normal distribution), meaning the probability of this result occurring by chance in a $\Lambda$CDM universe is less than one in a million.7

- Direction: The CatWISE dipole points towards $(l, b) \approx (238^\circ, 29^\circ)$. While this is offset from the CMB dipole by about $27^\circ$, it is statistically consistent with alignment given the uncertainties and the potential influence of the “Clustering Dipole” (discussed in Section 6).

4.2 The Argument for Orthogonality

The confirmation of the dipole anomaly with quasars is a pivotal moment in this field because of the orthogonality of the datasets:

- Physical Mechanism: Radio galaxies are detected via synchrotron radiation from relativistic jets and lobes. CatWISE quasars are detected via thermal emission from hot dust in the accretion torus. These are distinct physical processes involving different particle populations.

- Instrumental Systematics: Radio surveys use ground-based interferometers (VLA, ASKAP) subject to atmospheric and ionospheric noise, RFI, and UV-coverage limitations. CatWISE uses a space-based photometer (WISE) subject to scan-pattern artifacts and zodiacal light. The systematics are uncorrelated.

- Sample Overlap: There is very little overlap between the NVSS and CatWISE catalogs (less than 10% of sources are common to both). They essentially probe two independent populations of the Universe.15

The fact that two completely independent surveys, using different wavelengths and instruments, both find a dipole that is aligned with the CMB but has an amplitude excess of factor $\sim 2-3$ makes it extremely difficult to attribute the anomaly to a specific instrument error. It points strongly towards a genuine cosmological signal.2

5. Statistical Methodologies and Tension Quantification

The measurement of the cosmic dipole is a subtle statistical problem. The signal ($\sim 1\%$) is small, and the noise (Poissonian and systematic) can be significant.

5.1 Estimators: Linear vs. Quadratic

Early studies often used linear estimators, summing the direction vectors of all sources. While intuitive, linear estimators are biased by non-uniform sky coverage (masks). Modern analyses, such as those by Secrest et al. and Wagenveld et al., employ quadratic or maximum likelihood estimators (MLE). These methods fit a model of the number density field (monopole + dipole + quadrupole) to the data, properly accounting for the mask and the covariance between multipoles.16

5.2 Bayesian Frameworks

Recent work has moved towards Bayesian analysis to rigorously quantify the tension. Oayda et al. (2025) presented a Bayesian hierarchical model that jointly analyzes Planck, NVSS, RACS, and CatWISE.

- Evidence Ratios: They computed the Bayesian evidence for models where the dipole is fixed to the CMB kinematics versus models where the dipole parameters are free.

- Results: The “free dipole” model is strongly favored by the data. The analysis indicates “severe tension” ($>5\sigma$) between the Planck kinematic prior and the CatWISE likelihood.

- Concordance: Crucially, the Bayesian analysis reveals a “strong concordance” between CatWISE and NVSS. Their posteriors for the dipole amplitude and direction overlap, suggesting they are observing the same underlying phenomenon, even though it disagrees with the CMB.3

5.3 The Look-Elsewhere Effect

Critics might argue that searching for anomalies in multiple catalogs incurs a “look-elsewhere” penalty. However, the dipole test is a specific, a priori prediction of the standard model. The direction is fixed by the CMB, and the amplitude is fixed by the source counts. There are no free parameters to tune. Therefore, the high significance levels reported are robust against look-elsewhere criticisms.17

6. Systematic Effects and Counter-Arguments

Before accepting the conclusion that the Universe violates the CP, one must exhaustively explore all possible systematic errors.

6.1 Masking and Mode Coupling

The Galaxy obscures a significant portion of the sky (roughly 20-40% depending on the wavelength). This missing data destroys the orthogonality of spherical harmonics, causing “mode coupling.” Power from the monopole and quadrupole can leak into the dipole.

- Critique: Abghari et al. (2024) suggested that when the mode coupling matrix is properly accounted for, the uncertainty on the dipole increases significantly, potentially reducing the tension to $<3\sigma$. They argued that the intrinsic quadrupole of the quasar distribution is unknown and degenerate with the dipole.7

- Rebuttal: Secrest et al. (2025) and Bashir et al. (2025) countered this with extensive forward modeling using FLASK simulations. They generated mock catalogs with standard $\Lambda$CDM clustering and applied the exact survey masks. Their results show that while mode coupling does increase variance, it does not induce a systematic bias in the amplitude. The observed signal in CatWISE is far outside the distribution of mock dipoles, even with severe masking. They conclude that mode coupling cannot explain the factor of $\sim 2$ excess.7

6.2 The Clustering Dipole

The measured dipole is the vector sum of the kinematic dipole (our motion) and the clustering dipole (actual large-scale structure).

$$\vec{D}_{\text{obs}} = \vec{D}_{\text{kin}} + \vec{D}_{\text{clus}}$$

In a homogeneous universe, $\vec{D}_{\text{clus}}$ should converge to zero as the survey volume increases. However, for finite surveys, “cosmic variance” persists.

- Local Structure: Structures like the Shapley Concentration could mimic a dipole. However, quasars and radio galaxies are at high redshift ($z \sim 1$). The contribution of local ($z < 0.1$) structure to the projected dipole of such distant sources is negligible.3

- Random Alignment: For the clustering dipole to explain the anomaly, it would have to be (a) large (comparable to the kinematic term) and (b) aligned with the kinematic dipole. The probability of a random LSS vector aligning with the solar motion vector to within $\sim 20^\circ$ is roughly $1\%$. The fact that this alignment is seen in multiple independent surveys makes the “random clustering” hypothesis highly unlikely.5

6.3 Star-Galaxy Separation

In infrared surveys, stars can mimic quasars. Stars have a dipole due to solar motion and galactic rotation, but this dipole is distinct from the cosmic one.

- Directionality: The stellar dipole is dominated by the gradient of the Milky Way, pointing towards the Galactic Center $(0^\circ, 0^\circ)$.

- Effect: If the CatWISE sample were contaminated by stars, the measured dipole vector would be pulled towards the Galactic Center. The observed CatWISE dipole points to $(238^\circ, 29^\circ)$, which is nearly orthogonal to the Galactic Center. Therefore, stellar contamination would likely dilute the anomaly rather than create it. Removing stars more aggressively would likely increase the tension.15

6.4 Redshift Evolution and Tomography

One subtle theoretical systematic involves the evolution of source populations. The standard Ellis-Baldwin formula assumes a static population.

- The Dalang-Bonvin Correction: Dalang and Bonvin (2022) showed that if the number density or luminosity function of sources evolves with redshift, additional terms enter the dipole equation. These terms arise because the Doppler shift changes the observed redshift, and if the selection function depends on redshift, this creates a secondary dipole.20

- Impact: While theoretically important, applying these corrections to current datasets has not resolved the tension. In some cases, the evolution terms can actually increase the predicted kinematic dipole, making the observed excess slightly smaller but still significant.

- Tomography Results: Preliminary tomographic analyses (splitting sources into redshift bins) suggest that the dipole amplitude may be redshift-dependent. If the derived velocity $v(z)$ increases with redshift, this would effectively rule out a simple kinematic origin (which requires a constant $v$) and point towards bulk flows or intrinsic anisotropy.20

7. Theoretical Interpretations: Beyond $\Lambda$CDM

If systematics cannot explain the $5\sigma$ tension, we are forced to consider physical mechanisms that violate the standard FLRW assumptions.

7.1 Large-Scale Bulk Flows and “Dark Flow”

The most direct physical interpretation of the excess dipole is that the matter rest frame is moving relative to the CMB frame. This is known as a “bulk flow.”

- Scale: The standard model predicts bulk flows should decay on scales $> 100$ Mpc. The dipole anomaly implies a coherent flow extending to $z \sim 1$ (billions of light years).

- Kashlinsky’s Dark Flow: In 2008, Kashlinsky et al. claimed to detect a bulk flow of $\sim 600-1000$ km s$^{-1}$ using the kinetic Sunyaev-Zel’dovich (kSZ) effect in galaxy clusters. While controversial and challenged by Planck kSZ results, the magnitude of the “Dark Flow” is remarkably similar to the velocity implied by the radio/quasar dipole anomaly.22

- Implication: A flow on this scale suggests the influence of super-horizon fluctuations—gravitational gradients originating from beyond the observable Universe. This could imply that our Hubble patch is sliding towards a massive inhomogeneity outside our horizon.24

7.2 Dipole Cosmology and Tilted Bianchi Models

The FLRW metric assumes zero shear and zero tilt. However, the Einstein equations allow for homogeneous but anisotropic solutions, known as Bianchi models.

- The “Tilt”: In a “tilted” Bianchi universe (specifically Type V or VII$_h$), the cosmic fluid has a global velocity field relative to the geometric expansion.

- Krishnan et al. (2023): Proposed a “Dipole Cosmology” framework. They showed that in these models, the relative velocity between the matter fluid and the radiation fluid can grow over cosmic time. This would naturally explain why the CMB dipole (radiation frame) and the quasar dipole (matter frame) differ in amplitude. They share a direction (the axis of the tilt) but decouple dynamically.25

- Observables: These models predict specific signatures in the Hubble diagram (a dipole in $H_0$) and parity-violating modes in the CMB polarization, which are currently being searched for.

7.3 Modified Gravity and Dark Energy

The cosmic dipole tension may also signal a breakdown of General Relativity on large scales.

- Horndeski Theories: Certain classes of scalar-tensor theories (like Horndeski gravity) allow for effective gravitational couplings that vary with scale or direction. If dark energy is not a cosmological constant but a dynamic field (quintessence) with a gradient, it could induce an anisotropic expansion.27

- Early Dark Energy (EDE): Models of EDE, proposed to solve the Hubble Tension, might also leave imprints on large-scale anisotropy. If the scalar field associated with EDE had spatial fluctuations, it could generate a large-scale mode that resembles a dipole.28

7.4 Connections to Other Anomalies

The Dipole Anomaly is likely connected to other tensions in cosmology:

- The Hubble Tension: A large local bulk flow would bias local measurements of $H_0$. If we are in a bulk flow of $\sim 1000$ km s$^{-1}$, this could account for a significant fraction of the difference between Supernova ($H_0 \sim 73$) and CMB ($H_0 \sim 67$) measurements.3

- Hemispherical Asymmetry: The CMB exhibits a power asymmetry (one hemisphere is “smoother” than the other). The axis of this asymmetry aligns closely with the dipole. A single physical mechanism—such as a modulation of the primordial power spectrum by a super-horizon mode—could generate both the power asymmetry and the enhanced kinematic dipole.30

8. Future Prospects: Resolving the Anomaly

The next decade will see a definitive resolution to the Cosmic Dipole Anomaly, driven by three flagship observatories.

8.1 The Euclid Mission (ESA)

Launched in 2023, Euclid will survey 15,000 square degrees of the sky in the visible and near-infrared.

- Cosmic Infrared Background (CIB): Euclid will measure the dipole of the CIB by integrating the light of all resolved galaxies. This method is independent of the number-count thresholding used in CatWISE. Forecasts suggest Euclid will measure the CIB dipole direction to sub-degree accuracy and the amplitude with extremely high signal-to-noise ($>50\sigma$).32

- Tomography: Euclid‘s spectroscopic redshifts will allow for precise measurement of the dipole as a function of redshift ($0.9 < z < 1.8$). Observing a variation in $\mathcal{D}(z)$ would be the “smoking gun” for non-kinematic physics.33

8.2 The Square Kilometre Array (SKA)

The SKA will be the ultimate radio survey machine.

- Source Counts: SKA will detect hundreds of millions of radio sources (compared to NVSS’s 2 million). This will reduce Poisson noise to negligible levels.

- Precision: Forecasts indicate that SKA will constrain the dipole direction to within $\sim 4^\circ$ and the amplitude to within $10\%$. This precision is sufficient to distinguish between the kinematic prediction ($\mathcal{D} \sim 0.005$) and the anomalous value ($\mathcal{D} \sim 0.015$) at $>10\sigma$.34

- HI Intensity Mapping: SKA will also measure the dipole using 21cm intensity mapping, a completely different tracer than continuum counts, providing an internal cross-check.36

8.3 The Vera C. Rubin Observatory (LSST)

The LSST will conduct the Legacy Survey of Space and Time, mapping the Southern sky every few nights.

- Systematics Control: LSST’s unique “dithering” strategy and rapid revisit rate allow for exquisite control over calibration systematics, which are the main counter-argument against the current dipole results.

- Third Orthogonal Probe: LSST will provide a deep optical galaxy sample. Comparing the optical dipole (LSST) with the radio (SKA) and IR (Euclid) dipoles will provide a rigorous “triangulation” of the anomaly. If all three agree on an excess, the case for new physics will be irrefutable.37

9. Conclusion

The Cosmic Dipole Anomaly has graduated from a statistical curiosity to a central crisis in modern cosmology. The convergence of evidence from radio galaxies and infrared quasars points to a persistent, high-significance ($>5\sigma$) discrepancy between the Universe’s matter frame and its radiation frame.

The standard kinematic interpretation—that the CMB dipole is due solely to our motion of 370 km s$^{-1}$—is increasingly untenable in the face of matter dipoles that imply velocities of $\sim 1000$ km s$^{-1}$. The “orthogonality” of the radio and quasar datasets makes instrumental systematics an unlikely explanation. While theoretical refinements like redshift evolution and LSS clustering must be accounted for, they have so far failed to close the gap.

We are left with two profound possibilities. Either we have identified a subtle, pervasive systematic error that affects all flux-limited surveys across the electromagnetic spectrum, or the Cosmological Principle is violated. If the latter is true, we may inhabit a “tilted” Universe, flowing through the cosmos relative to the light of the Big Bang, or a Universe influenced by the gravitational ghosts of pre-inflationary structure.

The resolution is imminent. With Euclid taking data and SKA and Rubin on the horizon, the next few years will determine whether the Cosmic Dipole Anomaly is the final crack that shatters the FLRW metric, or a subtle lesson in the complexities of observing the cosmos. Until then, the “lopsided universe” remains one of the most compelling clues that our standard model of cosmology is incomplete.

Comparison of Cosmic Dipole Measurements

Dataset Type Frequency/Band Source Count Dipole Amplitude (×10−2) Kinematic Exp. (×10−2) Tension Reference CMB (Planck) Radiation Microwave N/A $0.123$ (velocity) N/A N/A 3 NVSS Radio Galaxies 1.4 GHz $1.8 \times 10^6$ $1.5 – 2.5$ $\sim 0.5$ $>2\sigma$ 3 TGSS Radio Galaxies 150 MHz $0.6 \times 10^6$ $2.0 – 6.0$ $\sim 0.5$ $>3\sigma$ 5 RACS Radio Galaxies 887 MHz $2.1 \times 10^6$ $\sim 1.5 – 2.0$ $\sim 0.5$ Strong 6 CatWISE Quasars Mid-IR (W1/W2) $1.35 \times 10^6$ $1.55 \pm 0.16$ $0.70$ $4.9\sigma$ 2 Combined Multi-tracer All $>4 \times 10^6$ $1.5 – 2.0$ $\sim 0.6$ $>5\sigma$ 8 Table 1: Summary of major dipole measurements compared to the kinematic expectation.

Works cited

- Colloquium: The Cosmic Dipole Anomaly – arXiv, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://arxiv.org/html/2505.23526v1

- (PDF) Colloquium: The Cosmic Dipole Anomaly – ResearchGate, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/392204608_Colloquium_The_Cosmic_Dipole_Anomaly

- Cosmic dipole tensions: confronting the cosmic microwave background with infrared and radio populations of cosmological sources – Oxford Academic, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/543/4/3229/8266509

- The kinematic contribution to the cosmic number count dipole – arXiv, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://arxiv.org/html/2503.02470v1

- Resolution of the incongruency of dipole asymmetries within various large radio surveys – implications for the Cosmological Principle – Oxford Academic, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/528/4/5679/7604001

- Overdispersed radio source counts and excess radio dipole detection – arXiv, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://arxiv.org/html/2509.16732v1

- The CatWISE2020 Quasar dipole: A Reassessment of the Cosmic Dipole Anomaly – arXiv, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://arxiv.org/html/2511.00822v1

- [2505.23526] Colloquium: The Cosmic Dipole Anomaly – arXiv, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.23526

- Are radio surveys showing us that the Cosmological Principle doesn’t hold up? – Astrobites, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://astrobites.org/2024/02/14/ur-template-post-title-2/

- The Rotating Universe: Radio Galaxies and the Cosmic Dipole Anomaly, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://spacefed.com/astronomy/the-rotating-universe-radio-galaxies-and-the-cosmic-dipole-anomaly/

- Kinematically Induced Dipole Anisotropy in Line-Emitting Galaxy Number Counts and Line Intensity Maps – arXiv, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://arxiv.org/pdf/2501.09800

- Resolution of the incongruency of dipole asymmetries within various large radio surveys – implications for the Cosmological Principle – ResearchGate, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/378315283_Resolution_of_the_incongruency_of_dipole_asymmetries_within_various_large_radio_surveys_-_implications_for_the_Cosmological_Principle

- Cosmic dipole tensions: confronting the Cosmic Microwave Background with infrared and radio populations of cosmological sources – arXiv, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://arxiv.org/html/2509.18689v1

- [2511.00822] The CatWISE2020 Quasar dipole: A Reassessment of the Cosmic Dipole Anomaly – arXiv, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.00822

- The Dipole Problem in Cosmology – Indico Global, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://indico.global/event/1728/contributions/30544/attachments/15592/24877/The%20Dipole%20Problem%20in%20Cosmology.pdf

- Cosmic Multipoles in Galaxy Surveys II: Comparing Different Methods in Assessing the Cosmic Dipole | Published in The Open Journal of Astrophysics, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://astro.theoj.org/article/144907-cosmic-multipoles-in-galaxy-surveys-ii-comparing-different-methods-in-assessing-the-cosmic-dipole

- Reassessment of the dipole in the distribution of quasars on the sky – arXiv, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://arxiv.org/html/2405.09762v2

- The CatWISE2020 Quasar dipole: A Reassessment of the Cosmic Dipole Anomaly, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/397232239_The_CatWISE2020_Quasar_dipole_A_Reassessment_of_the_Cosmic_Dipole_Anomaly

- Clustering properties of the CatWISE2020 quasar catalogue and their impact on the cosmic dipole anomaly – ResearchGate, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/397006102_Clustering_properties_of_the_CatWISE2020_quasar_catalogue_and_their_impact_on_the_cosmic_dipole_anomaly

- Redshift tomography of the kinematic matter dipole – University of Portsmouth, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://pure.port.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/106493259/Redshift_tomography_of_the_kinematic_matter_dipole.pdf

- On the kinematic cosmic dipole tension | Request PDF – ResearchGate, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359307883_On_the_kinematic_cosmic_dipole_tension

- [1411.4180] Probing the Dark Flow signal in WMAP 9 yr and PLANCK cosmic microwave background maps – arXiv, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://arxiv.org/abs/1411.4180

- Scientists Detect Cosmic ‘Dark Flow’ Across Billions of Light Years – NASA, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://www.nasa.gov/news-release/nasa-scientists-detect-cosmic-dark-flow-across-billions-of-light-years/

- Dark flow – Wikipedia, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dark_flow

- Dipole cosmology: the Copernican paradigm beyond FLRW | Request PDF – ResearchGate, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372211883_Dipole_cosmology_the_Copernican_paradigm_beyond_FLRW

- Towards a realistic dipole cosmology: the dipole ΛCDM model – ResearchGate, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/381707155_Towards_a_realistic_dipole_cosmology_the_dipole_LCDM_model

- Observations by DESI Open the Door to Modified Gravity Models – Universe Today, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://www.universetoday.com/articles/observations-by-desi-open-the-door-to-modified-gravity-models

- The “Hubble tension”: A growing crisis in cosmology – Math Scholar, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://mathscholar.org/2024/10/the-hubble-tension-a-growing-crisis-in-cosmology/

- Cosmic dipoles from large-scale structure surveys – ResearchGate, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/398345183_Cosmic_dipoles_from_large-scale_structure_surveys

- CMB-S4 and the hemispherical variance anomaly – Oxford Academic, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/470/1/372/3828090

- (PDF) Resolution to the CMB Hemispherical Asymmetry, Cold Spot, Quadrupole-Octupole, and Missing Large-Angle Correlations: Cosmological Coda III of the Principia Cybernetica – ResearchGate, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/399488032_Resolution_to_the_CMB_Hemispherical_Asymmetry_Cold_Spot_Quadrupole-Octupole_and_Missing_Large-Angle_Correlations_Cosmological_Coda_III_of_the_Principia_Cybernetica

- Euclid preparation XLVI. The near-infrared background dipole experiment with Euclid, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/items/e1aa01b4-bed9-4847-9bdf-ac24ca24ac33

- Euclid: Cosmological forecasts from the void size function – the University of Groningen research portal, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://research.rug.nl/files/603418851/aa44095_22.pdf

- PoS(AASKA14)032, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://pos.sissa.it/215/032/pdf

- Testing the standard model of cosmology with the SKA: the cosmic radio dipole | Request PDF – ResearchGate, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/345465646_Testing_the_standard_model_of_cosmology_with_the_SKA_the_cosmic_radio_dipole

- Testing the standard model of cosmology with the SKA: the cosmic radio dipole – CORE, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/195277694.pdf

- Examples of LSST Science Projects | Rubin Observatory, accessed on January 9, 2026, https://www.lsst.org/science/science_portfolio

- The Rubin Observatory Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), accessed on January 9, 2026, https://lsstdesc.org/pages/rubin.html

astronomy, Bulk Flow, CatWISE Quasars, CMB Dipole, Cosmic Anisotropy, Cosmic Dipole Anomaly, Cosmic Rest Frame, Cosmological Principle, Dark Flow, Dipole Anisotropy, Doppler Boosting, Ellis-Baldwin Test, Euclid Mission, FLRW Metric, Hubble Tension, Isotropy Violation, Kinematic Dipole, Lambda-CDM Model, Large-Scale Structure, LSST, Modern Cosmology Crisis, NVSS Radio Survey, philosophy, physics, Quasar Dipole, RACS Survey, Radio Galaxy Dipole, Relativistic Aberration, science, Solar Peculiar Motion, Square Kilometre Array, Tilted Universe Models, universe, Universe Homogeneity, Vera Rubin Observatory -

Ternary Computing: A Systematic Review of Optimal Logic, Balanced Architectures, and Emerging Frontiers in AI Networks and Qutrit Technology

Abstract: Ternary Computing: Structured Literature Review

This structured literature review provides a comprehensive analysis of Ternary Computing, spanning its foundational theory, architectural implementations, and emerging applications. Originating from the theoretical advantages of optimal radix economy and early prototypes like the Setun computer (1958), the field offers substantial benefits in information density and interconnect reduction over conventional binary systems. Key research themes reviewed include the evolution from discrete transistor-based logic to modern implementations using CMOS, CNTFETs, and Memristors, alongside the powerful computational symmetry of balanced ternary arithmetic.

The review highlights important studies establishing the superior efficiency of ternary logic in areas like Ternary Neural Networks (TNNs) and cybersecurity protocols. Persistent debates center on the trade-off between the complexity of fabricating reliable three-state devices (maintaining sufficient noise margin) versus the gains in system-level integration. Significant gaps remain in developing a viable, manufacturable, high-yield Ternary ALU and standardizing a cohesive Ternary Memory architecture. Future research should prioritize breakthroughs in tunneling-based solid-state devices and the practical implementation of Quantum Ternary Logic (Qutrits) to fully unlock non-binary computing’s promise.

Benefit of Ternary Computing for Analog Computing

Ternary logic benefits analog computing by enabling Multi-Valued Logic (MVL) implementations that increase the information density per wire and can reduce overall component count. This is often achieved via current-mode CMOS circuits, which inherently manage the multiple current levels of ternary logic, simplifying the design of high-dynamic-range converters like Ternary Digital-to-Analog Converters (DACs).

Advanced computer systems, Balanced ternary, CNTFET, Computer science literature, Digital system design, Future of computing, Logic gate design, Memristor logic, Multi-valued computing, Multi-valued logic, Multi-valued logic review, MVL, Non-binary computing, Quantum ternary logic, Qutrits, Setun computer, Ternary ALU, Ternary computer architecture, Ternary computing, TERNARY LOGIC, Ternary memory, Ternary neural networks, Ternary processors, Three-valued logic -

Unraveling Turbulent Heat Transport: Boundary Layers, Scalar Scaling, and the Ultimate Convection Debate

Abstract: Scalar Turbulence and Heat Transport Scaling in High-Rayleigh Number Convection

This structured literature review synthesizes the theoretical and experimental foundations concerning scalar turbulence and heat transport scaling in high-Rayleigh number (Ra) Rayleigh–Bénard convection (RBC), focusing on the critical role of thermal boundary layers (TBLs). The primary objective is to critically assess the evolution, central tenets, and ongoing debates surrounding the dominant heat flux scaling laws, particularly the predicted $\text{Nu} \propto \text{Ra}^{2/7}$ relationship.

The review traces the evolution of understanding from the classical $\text{Nu} \propto \text{Ra}^{1/3}$ prediction to the foundational Shraiman and Siggia (SS) $\text{Ra}^{2/7}$ scaling, which hinges on a passive scalar approximation for temperature advection within the turbulent bulk and distinct boundary layer turbulence dynamics. Key themes explored include the interplay between bulk turbulence (often described by Kolmogorov scaling) and the unique characteristics of the TBLs, the mechanism of plume dynamics (the primary mode of heat transport), and the theoretical structure proposed by Grossmann and Lohse (GL), which attempts a unified description of the Nusselt ($\text{Nu}$) and Reynolds ($\text{Re}$) numbers across various Ra and Prandtl ($\text{Pr}$) regimes.

A central finding is the persistent, yet increasingly constrained, debate between the $\text{Ra}^{2/7}$ and $\text{Ra}^{1/3}$ exponents, with modern high-Ra experiments and Direct Numerical Simulations (DNS) often yielding exponents that cluster near $0.28$ ($\approx 2/7$), especially in the proposed ‘soft’ or ‘intermediate’ turbulent regime. The primary conflicting viewpoint remains the validity of the passive scalar assumption in the bulk of this active, buoyancy-driven flow, which directly influences the predicted boundary layer velocity and temperature profiles.

Significant gaps remain in fully characterizing the flow structure in the proposed ‘ultimate’ regime ($\text{Ra} > 10^{14}$), particularly regarding the detailed scaling of the TBL velocity and the definitive role of the Large Scale Circulation (LSC). Future research should focus on high-fidelity, high-Ra DNS with sufficient resolution to resolve TBL microstructure, novel experimental techniques to directly measure logarithmic velocity profiles within the TBL, and advanced theoretical modeling that incorporates the full non-passive nature of the temperature field to reconcile observed scaling with theoretical predictions across all relevant Ra numbers.

The core findings and theoretical frameworks within the literature review on Scalar Turbulence and Heat Transport Scaling in High-Rayleigh Number Convection offer significant conceptual and structural insights that could be useful for addressing the Navier-Stokes Millennium Problem (specifically, the question of existence and smoothness of solutions for the 3D incompressible Navier-Stokes equations).

The utility stems from the literature’s focus on:

Scaling Laws and Singularities (The Core Problem)

The Millennium Problem is fundamentally about understanding whether the Navier-Stokes equations can lead to a singularity (infinite energy dissipation or velocity) in finite time.

- Turbulence Scaling ($\text{Nu} \propto \text{Ra}^{2/7}$): The literature review details how the $\text{Nu} \propto \text{Ra}^{2/7}$ and similar scaling laws are derived from assumptions about the structure of turbulence (like Kolmogorov $\text{K41}$ scaling) and the balance of energy/fluxes in the governing equations. These scaling relations are empirical and theoretical efforts to characterize the behavior of solutions at extreme parameters ($\text{Ra} \to \infty$).

- Analogy to Singularities: The theoretical debate between $\text{Nu} \propto \text{Ra}^{2/7}$ and the classical $\text{Ra}^{1/3}$ is essentially a debate over how energy dissipates as the system becomes more turbulent. A singularity in the Navier-Stokes equations would represent a point of infinite energy/vorticity dissipation. The scaling laws, while not proving or disproving singularities, provide a quantitative framework for how solutions should behave in the limit of infinite driving force ($\text{Ra}$), forcing theorists to identify the critical physical mechanism (e.g., the thermal boundary layer dynamics in the Shraiman & Siggia theory) that controls the flow.

Boundary Layers and Energy Dissipation

The literature emphasizes the crucial distinction between bulk turbulence and thermal boundary layers (TBLs).

- Dissipation Localization: In high-$\text{Ra}$ convection, a significant portion of the total energy (both kinetic and thermal) dissipation is confined to the thin TBLs. The Grossmann-Lohse (GL) theory explicitly formalizes this by partitioning the total dissipation into contributions from the bulk and the boundary layers.

- Relevance to Navier-Stokes: The Millennium Problem requires understanding if localized regions of extreme energy concentration can form. The $\text{RBC}$ studies show a physical mechanism for concentrating dissipation (the TBLs). Mathematical analysis of the Navier-Stokes equations could draw on this by investigating if the boundary layer structure provides a natural “regularizing” mechanism or, conversely, a prime location for the growth of potentially singular gradients.

Passive vs. Active Scalar Turbulence

The conflicting viewpoints section is highly relevant.

- Passive Scalar Approximation: The $\text{Nu} \propto \text{Ra}^{2/7}$ scaling relies on the assumption of passive scalar turbulence in the bulk (where temperature acts as a passive tracer). This is a simplification that allows for cleaner mathematical analysis.

- Mathematical Simplification: For the Navier-Stokes Problem, a common approach is to study simplified, related equations (like the Euler equations or 2D Navier-Stokes) that do have global smooth solutions. The $\text{RBC}$ literature demonstrates how the results change fundamentally when the active nature of the temperature field (buoyancy, the driving force) is correctly accounted for, moving beyond the passive scalar simplification. This provides a test case: any proposed proof for 3D Navier-Stokes must hold for the full, non-simplified equations where buoyancy is active.

In summary, the $\text{RBC}$ literature provides a mathematically tractable, physically realized system of equations closely related to Navier-Stokes ($\text{RBC}$ is $\text{Navier-Stokes} + \text{Temperature Field} + \text{Boussinesq}$ approximation). The efforts to derive and validate scaling exponents force a deep confrontation with the structure of solutions at high Reynolds numbers, which is the exact regime where the existence and smoothness of the pure Navier-Stokes solutions are questioned.

$\text{Nu} \propto \text{Ra}^{2/7}$, Buoyancy-Driven Flow, Convection boundary layer, fluid dynamics, Fluid mechanics research, Grossmann-Lohse theory, Heat transfer scaling, High Rayleigh number, Nusselt number scaling, Passive scalar, Plume dynamics, Rayleigh-Bénard Convection, Scalar turbulence, Scaling Laws, Shraiman and Siggia theory, Thermal boundary layers, Turbulence theory, Turbulent Convection, Ultimate regime convection -

Best Practices for Accessing, Viewing, and Editing James Webb Space Telescope Imagery: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract:

This literature review comprehensively synthesizes the evolving best practices for the full lifecycle of James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) imagery, from initial data retrieval to final public-facing aesthetic processing. The primary research themes cover Data Access and Archival, Scientific Calibration and Processing, and Aesthetic Visualization and Presentation.

The review establishes that the cornerstone of access lies with the NASA MAST archive, where data is primarily distributed in the complex, multi-extension FITS image format. Key studies emphasize the necessity of programmatic access using Python/Astropy and the JWST Pipeline for rigorous image calibration and correction of artifacts. The evolution of processing shows a shift from general-purpose tools to specialized pipelines like Astropy and community-developed solutions like Eureka!, underscoring the increasing complexity of mid-infrared data handling.

Best practices for visualization fall into two domains: quick-look scientific inspection via tools like SAOImage DS9 and advanced false-color compositing for public outreach. The latter involves a critical, non-trivial step of mapping shorter infrared wavelengths (e.g., NIRCam) to blue/cyan and longer wavelengths (e.g., MIRI) to red/gold, which requires specialized non-linear stretching. This review provides a structured workflow analysis and tool comparison, offering essential guidance for astronomers, data scientists, and astrophotographers seeking to move beyond raw data to scientifically accurate and compelling imagery.

Step-by-Step Guide for Working with JWST Imagery

Phase 1: Accessing and Downloading the Raw Data (The Archive)

This guide translates the specialized information from the literature review into a simple, three-stage workflow for accessing, viewing, and aesthetically editing JWST imagery. The process moves from the highly technical FITS data to a beautiful, public-ready image.

The most important source for all JWST data is the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST).

Step Action Best Practice / Finding from Review 1.1. Navigate to MAST Go to the official MAST Portal (mast.stsci.edu). This is the primary access point recommended for all first-time users. All publicly released JWST data is stored here. Programmatic access (APIs) is possible, but the web portal is best for beginners. 1.2. Search for Data Use the “Advanced Search” to filter by Mission: JWST and the Target Name (e.g., Carina Nebula or its catalogue ID, NGC3324). Searching by Target Name or a specific Program ID is the most effective way to locate a set of images for one object. 1.3. Select Files Identify the multiple files for your chosen target. You must download files from different filters (e.g., F090W, F150W, F444W) to create a color image. You need at least three filters to map to Red, Green, and Blue channels. For each filter, look for the highly processed file, typically ending in _i2d.fits(Level 3 or final calibrated data).1.4. Download Select your chosen files and use the Download Manager. Be aware that these files, in the FITS format, can be several gigabytes each. FITS is the universally used scientific format. You will need to disable pop-up blockers, as the download process often uses a pop-up window. 1.5. Extract the Science Data After unzipping, navigate through the folders. The actual image data you want is within the FITS file, specifically in the extension with the SCIheader.The FITS format is Multi-Extension (MEF). The first or primary extension is usually header information; the science data resides in a subsequent extension labeled SCI.Phase 2: Viewing and Basic Scientific Inspection (The Quick Look)

Since FITS files cannot be opened like a standard JPEG, you need specialized software.

Step Action Best Practice / Finding from Review 2.1. Install a FITS Viewer Download and install a dedicated FITS viewer like SAOImage DS9 (free and cross-platform). DS9 is the standard, most-cited tool for astronomers for quick viewing and inspection of FITS files. 2.2. Open the FITS Files Open each filter’s FITS file in DS9. If it opens in a solid black or white screen, you must adjust the stretch and scale. The data is in 32-bit floating-point format and must be contrast-stretched to become visible on an 8-bit screen. Use the scale options (e.g., Log, Sqrt, or ZScale) to reveal the detail. 2.3. Inspect Data Quality Use the view options to switch between the extensions within the file. Specifically, look at the ERR(error) andDQ(Data Quality) extensions.Best practice for scientific review is to check the Data Quality. The DQarray flags bad pixels, cosmic ray hits, and other artifacts that need to be masked or ignored during processing.2.4. Align the Images Since the multiple filter images may not be perfectly aligned, use DS9’s features to match them up, often using the World Coordinate System (WCS) option. Alignment is a critical prerequisite for creating a composite color image; the pixels of each filter must correspond exactly to the same location in space. Phase 3: Aesthetic Editing and False-Color Compositing (The Magazine Image)

This phase turns the multiple gray-scale FITS images into a single, vibrant, and informative color image.

Step Action Best Practice / Finding from Review 3.1. Convert to RGB Layers Export each of your contrast-stretched FITS images (e.g., three filters) into an easily editable 16-bit or 32-bit image format, such as TIFF. Recommended FITS Liberator 4 for stretching and creation of TIFF files. Standard image editors like GIMP or Photoshop (cited in the review) require TIFF or similar layered formats; they cannot natively handle FITS data. 3.2. Apply False Color Mapping In your image editor, assign your three TIFF files to the Red (R), Green (G), and Blue (B) color channels of a new RGB composite image. This is the most crucial step: Shorter Wavelength Blue/Cyan and Longer Wavelength Red/Gold is the widely accepted, scientifically-driven best practice. 3.3. Non-linear Stretching Apply aggressive, non-linear stretching (such as logarithmic or hyperbolic stretching) to the individual color channels to pull faint detail out of the background noise. This maximizes the Dynamic Range (HDR), making the image pop. It is what separates raw JWST data from the finished, magazine-quality public images. 3.4. Final Touches Fine-tune the color balance, remove noise/artifacts flagged in the DQimage, and sharpen the final composite.Aesthetic editing is an “art as much as a science.” The goal is a visually compelling image that remains true to the scientific assignment of color. The key to creating professional-grade JWST imagery is to embrace the programmatic access and advanced tools, as demonstrated in this video tutorial: Easiest Way to Download JWST Data.

artificial intelligence, Astrophotography editing guide, Astropy Python JWST, digital-marketing, FITS image editing for astrophotography, GIMP Photoshop astronomy, James Webb Space Telescope data guide, JWST false color mapping, JWST FITS file access, JWST image calibration workflow, JWST image processing tutorial, JWST image viewing DS9, marketing, NASA MAST archive download, open-source astronomy tools, photography, SAOImage DS9 tutorial, Space telescope data processing, Webb telescope data analysis -

The Spectroscopic Frontier: A Comprehensive Review of Exoplanet Atmospheric Characterization in the JWST Era

Abstract

This literature review examines the dramatic advancements in exoplanet atmospheric characterization, charting the field’s transition from initial detections to detailed, high-fidelity spectroscopic analyses in the era of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

The foundational observational techniques—Transmission Spectroscopy (Charbonneau et al. ) and Secondary Eclipse/Emission Spectroscopy (Deming et al. )—have been augmented by the deployment of High-Resolution Spectroscopy (HRS) for dynamic studies and the integration of high-contrast integral field spectroscopy on next-generation instruments like the Extremely Large Telescope’s (ELT) HARMONI for molecule mapping.

The advent of JWST has driven immediate breakthroughs, providing the first definitive evidence of complex photochemistry (SO2 and CO2 on WASP-39b ), enabling the characterization of the notoriously opaque sub-Neptune GJ 1214b below its thick haze layer , and identifying the intriguing Hycean candidate K2-18b through the detection of carbon-bearing molecules.

This influx of high-precision data has exposed critical methodological and physical hurdles. Computationally, the complexity and volume of JWST spectra have rendered traditional Bayesian retrieval methods prohibitively expensive. This challenge is being addressed by a paradigm shift toward amortized inference using neural networks (e.g., FASTER), which performs practically instantaneous Bayesian analysis and model comparison. Physically, persistent debates center on the cloud/haze degeneracy problem and the revelation that imperfect stellar models introduce significant systematic errors in emission spectroscopy, even for high-precision JWST data.

For future research, the review highlights critical gaps, particularly the severe data scarcity for temperate rocky exoplanets and the theoretical disconnect between retrieved atmospheric compositions and protoplanetary disk evolution. The search for biosignatures must adhere to the principle of life as the “hypothesis of last resort” , requiring comprehensive contextual observations to rigorously rule out abiotic false positives. Future success hinges on the coordinated synergy between the statistical census capabilities of missions like ARIEL and the dynamical mapping capabilities of ELT-class ground-based facilities , prioritizing large-scale, multi-transit campaigns to characterize habitable-zone worlds.

Advances in Exoplanet Atmospheric Characterization: Techniques, Discoveries, and Future Prospects

I. Introduction and Historical Context

I.A. Defining the Scientific Imperative and Scope of Characterization

Exoplanet atmospheric characterization represents the critical pivot in exoplanetary science, moving research beyond the statistical detection of new worlds toward the detailed investigation of their physical and chemical states. This undertaking is paramount, as the atmosphere serves as the observable link connecting a planet’s formation mechanisms, its long-term evolution, and its ultimate potential for supporting life. The scope of characterization has expanded dramatically, evolving from the initial measurement of bulk planetary properties (mass, radius) to an exhaustive spectroscopic census that seeks to determine atmospheric composition, thermal structure, and dynamic processes, including global circulation patterns and atmospheric loss.1 These comprehensive investigations are essential for interpreting the conditions that prevail on extrasolar planets.

I.B. The Foundational Era: From Detection to First Light

The current capability for atmospheric characterization is entirely dependent upon the foundational techniques of radial velocity and transit photometry, which established the prerequisite bulk parameters—mass, radius, and orbital configuration—necessary to select viable targets.

The characterization era was inaugurated by landmark spectroscopic achievements utilizing the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). The first robust detection of an exoplanet atmosphere was reported by Charbonneau et al. in 2002.2 Using the HST’s STIS spectrograph, the team measured absorption from atomic Sodium (Na D lines) in the optical transmission spectrum of the hot Jupiter HD209458b, detecting a signal at a level of percent.2 This successful detection established transmission spectroscopy as the primary early tool for probing exoplanetary envelopes. It is important to note that the difficulty encountered in confirming this Na detection from ground-based telescopes at the time, due to pervasive systematic effects and contamination, directly foreshadowed the subsequent necessary development of High-Resolution Spectroscopy (HRS).1 The limitations imposed by telluric (Earth’s atmospheric) and stellar contamination became the driving force necessitating the technological shift toward instruments capable of high spectral resolving power for effective isolation of the planetary signal.1

Following the success of transmission spectroscopy, the field rapidly progressed to measure thermal emission. Deming et al. (2005) pioneered occultation spectroscopy, or secondary eclipse spectroscopy, demonstrating the ability to measure the planet’s emitted light when it passes behind its host star.3 This technique provided the first constraints on dayside temperature profiles. The success of occultation spectroscopy served as a critical foundational justification for the design requirements and wavelength coverage specifications of future large, cryogenic space observatories, recognizing the inherent need for high-sensitivity infrared capabilities realized today by JWST.3