Circular Astronomy

Twitter List – See all the findings and discussions in one place

-

The Mysterious Discovery of JWST That No One Saw Coming

Are We Inside a Cosmic Whirlpool? Recent JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES) observations of mysterious cosmological anomalies in the rotational patterns of galaxies challenge our understanding of the universe and reveal surprising connections to natural growth patterns.

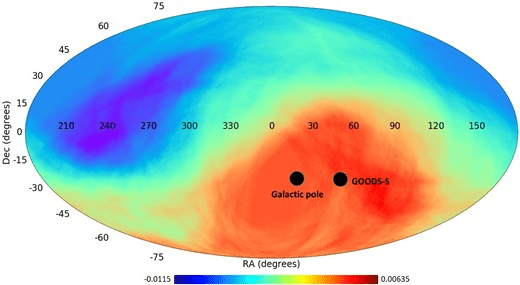

The rotation of 263 galaxies has been studied by Lior Shamir of Kansas State University, with 158 rotating clockwise and 105 rotating counterclockwise. The number of galaxies rotating in the opposite direction relative to the Milky Way is approximately 1.5 times higher than those rotating in the same direction.

New Cosmological anomalies that challenge our cosmological models and would have angered Einstein.

This observation challenges the expectation of a random distribution of galaxy rotation directions in the universe based on the isotropy assumption of the Cosmological Principle.

This is certainly not something Einstein would have liked to hear during his lifetime, but it would have excited Johannes Kepler.

What does this mean for our cosmological models, and why would it make Johannes Kepler happy?

The 1.5 ratio in galaxy rotation bias is intriguingly close to the Golden Ratio of 1.618. The Golden Ratio was one of Johannes Kepler’s two favorites. The astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) referred to the Golden Ratio as one of the “two great treasures of geometry” (the other being the Pythagorean theorem). He noted its connection to the Fibonacci sequence and its frequent appearance in nature.

What is the Fibonacci sequence?

The Italian mathematician Leonardo of Pisa, better known as Fibonacci, introduced the world to a fascinating sequence in his 1202 book Liber Abaci (The Book of Calculation). This sequence, now famously known as the Fibonacci sequence, was presented through a hypothetical problem involving the growth of a rabbit population.

The growth of a rabbit population and why it matters?

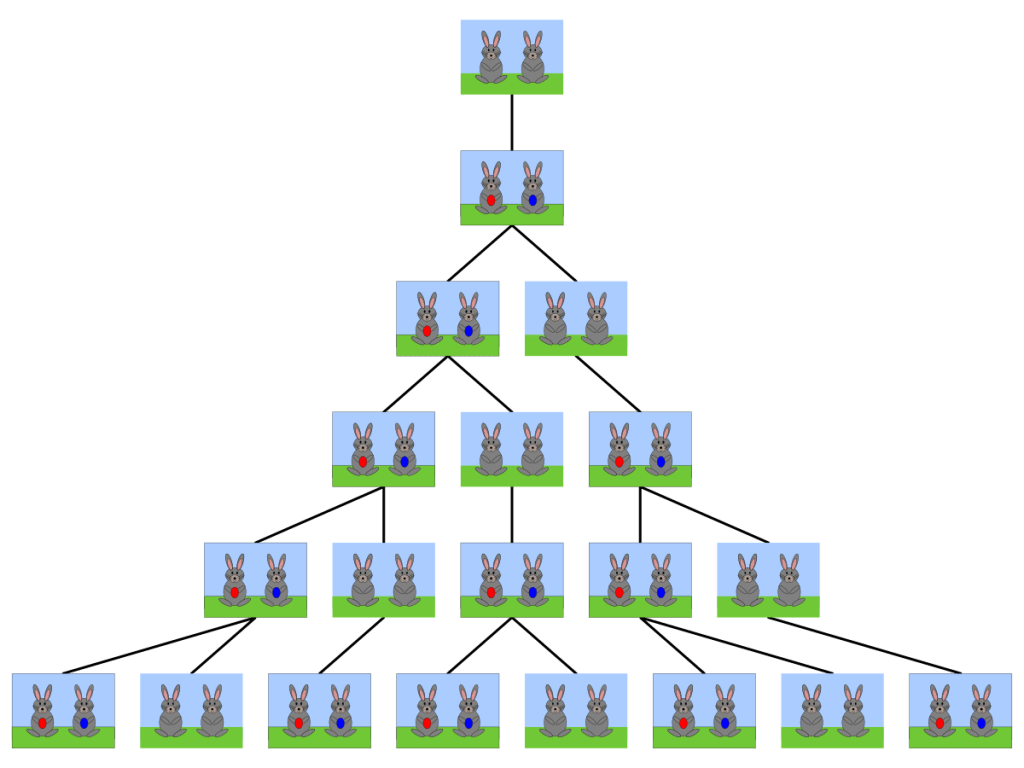

Fibonacci posed the following question: Suppose a pair of rabbits can reproduce every month starting from their second month of life. If each pair produces one new pair every month, how many pairs of rabbits will there be after a year?

The solution unfolds as follows:

- In the first month, there is 1 pair of rabbits.

- In the second month, there is still 1 pair (not yet reproducing).

- In the third month, the original pair reproduces, resulting in 2 pairs.

- In the fourth month, the original pair reproduces again, and the first offspring matures and reproduces, resulting in 3 pairs.

Image Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FibonacciRabbit.svg

This pattern continues, with each new generation adding to the total, where each term is the sum of the two preceding terms.

The Fibonacci sequence generated is: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, …

While this idealized model of a rabbit population assumes perfect conditions—no sickness, death, or other factors limiting reproduction—it reveals a growth pattern that approaches the Golden Ratio as the sequence progresses. The ratio is determined by dividing the current population by the previous population. For example, if the current population is 55 and the previous population is 34, based on the Fibonacci sequence above, the ratio of 55/34 is approximately 1.618.

However, in reality, the growth rate of a rabbit population would likely fall below this mathematical ideal ratio due to natural constraints.Yet, this growth (evolutionary) pattern appears quite often in nature, such as in the growth patterns of succulents.

The growth patterns in succulents often follow the Fibonacci sequence, as seen in the arrangement of their leaves, which spiral around the stem in a way that maximizes sunlight exposure. This spiral phyllotaxis reflects Fibonacci numbers, where the number of spirals in each direction typically corresponds to consecutive terms in the sequence.

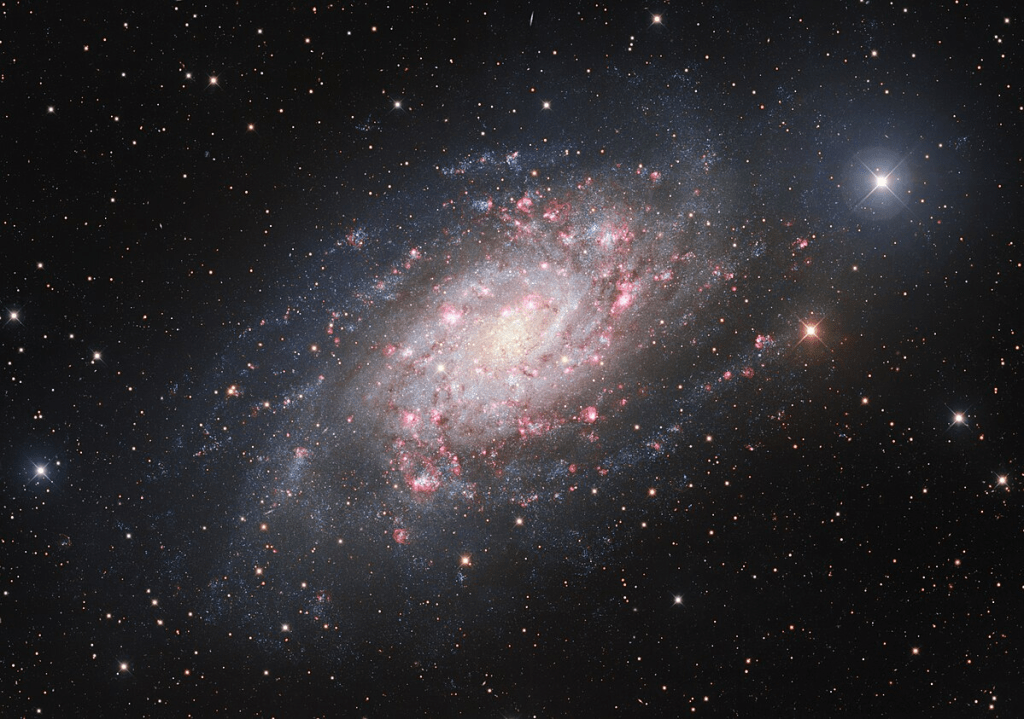

Spiral galaxies exhibit a similar growth (evolutionary) pattern in their spiral arms.

Spiral galaxies, like the Milky Way, display strikingly similar growth patterns in their spiral arms, where new stars are continuously formed and not in the center of the galaxy.

Image Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_Galaxy_of_Birth_and_Death.jpg

Returning to the observations and research conducted by Lior Shamir of Kansas State University using the JWST.

The most galaxies with clockwise rotation are the furthest away from us.

The GOODS-S field is at a part of the sky with a higher number of galaxies rotating clockwise

Image Source: Figure 10 https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staf292

“If that trend continues into the higher redshift ranges, it can also explain the higher asymmetry in the much higher redshift of the galaxies imaged by JWST. Previous observations using Earth-based telescopes e.g., Sloan Digital Sky Survey, Dark Energy Survey) and space-based telescopes (e.g., HST) also showed that the magnitude of the asymmetry increases as the redshift gets higher (Shamir 2020d).” Source: [1]“It becomes more significant at higher redshifts, suggesting a possible link to the structure of the early universe or the physics of galaxy rotation.” Source: [1]

Could the universe itself be following the same growth patterns we see in nature and spiral galaxies?

This new observation by Lior Shamir is particularly intriguing because, if we were to shift the perspective of our standard cosmological model—from one based on a singularity (the Big Bang ‘explosion’), which is currently facing a lot of challenges [2], to a growth (evolutionary) model—we would no longer be observing the early universe. Instead, we would be witnessing the formation of new galaxies in the far distance, presenting a perspective that is the complete opposite of our current worldview (paradigm).

NEW: Massive quiescent galaxy at zspec = 7.29 ± 0.01, just ∼700 Myr after the “big bang” found.

RUBIES-UDS-QG-z7 galaxy is near celestial equator.

It is considered to be a “massive quiescent galaxy’ (MQG).

These galaxies are typically characterized by the cessation of their star formation.

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/adab7a

The rotation, whether clockwise or counterclockwise, has not yet been observed.Reference

The distribution of galaxy rotation in JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey

Lior Shamir

[1 ] https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/538/1/76/8019798?login=false

The Hubble Tension in Our Own Backyard: DESI and the Nearness of the Coma Cluster

Daniel Scolnic, Adam G. Riess, Yukei S. Murakami, Erik R. Peterson, Dillon Brout, Maria Acevedo, Bastien Carreres, David O. Jones, Khaled Said, Cullan Howlett, and Gagandeep S. Anand

[2] https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2041-8213/ada0bd

Reading Recommendation:

The Golden Ratio, Mario Livio, 2002

Mario Livio was an astrophysicist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, which operates the Hubble Space Telescope.

RUBIES Reveals a Massive Quiescent Galaxy at z = 7.3

Andrea Weibel, Anna de Graaff, David J. Setton, Tim B. Miller, Pascal A. Oesch, Gabriel Brammer, Claudia D. P. Lagos, Katherine E. Whitaker, Christina C. Williams, Josephine F.W. Baggen, Rachel Bezanson, Leindert A. Boogaard, Nikko J. Cleri, Jenny E. Greene, Michaela Hirschmann, Raphael E. Hviding, Adarsh Kuruvanthodi, Ivo Labbé, Joel Leja, Michael V. Maseda, Jorryt Matthee, Ian McConachie, Rohan P. Naidu, Guido Roberts-Borsani, Daniel Schaerer, Katherine A. Suess, Francesco Valentino, Pieter van Dokkum, and Bingjie Wang (王冰洁)

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/adab7a

Appendix Spiral Galaxies:

Spiral galaxies are known for their stunning and symmetrical spiral arms, and many of them exhibit patterns that approximate logarithmic spirals, which are mathematically related to the Golden Ratio. While not all spiral galaxies perfectly follow the Golden Ratio, some exhibit spiral arm structures that closely resemble this pattern. Here are some notable examples of spiral galaxies with logarithmic spiral patterns:

1. Milky Way Galaxy

- Our own galaxy, the Milky Way, is a barred spiral galaxy with arms that approximate logarithmic spirals. The four primary spiral arms (Perseus, Sagittarius, Scutum-Centaurus, and Norma) follow a logarithmic pattern, though not perfectly aligned with the Golden Ratio.

2. M51 (Whirlpool Galaxy)

- The Whirlpool Galaxy is one of the most famous examples of a spiral galaxy with well-defined logarithmic spiral arms. Its arms are nearly symmetrical and exhibit a pattern that closely resembles the Golden Ratio.

3. M101 (Pinwheel Galaxy)

- The Pinwheel Galaxy is a grand-design spiral galaxy with prominent and well-defined spiral arms. Its structure is often cited as an example of a logarithmic spiral in astronomy.

4. NGC 1300

- NGC 1300 is a barred spiral galaxy with a striking logarithmic spiral pattern in its arms. It is often studied for its near-perfect spiral structure.

5. M74 (Phantom Galaxy)

- The Phantom Galaxy is another grand-design spiral galaxy with arms that follow a logarithmic spiral pattern. Its symmetry and structure make it a textbook example of this phenomenon.

6. NGC 1365

- Known as the Great Barred Spiral Galaxy, NGC 1365 has a prominent bar structure and spiral arms that exhibit a logarithmic pattern.

7. M81 (Bode’s Galaxy)

- Bode’s Galaxy is a spiral galaxy with arms that follow a logarithmic spiral structure. It is one of the brightest galaxies visible from Earth and a popular target for astronomers.

8. NGC 2997

- This galaxy is a grand-design spiral galaxy with arms that closely resemble logarithmic spirals. It is located in the constellation Antlia.

9. NGC 4622

- Known as the “Backward Galaxy,” NGC 4622 has a unique spiral structure with arms that follow a logarithmic pattern, though its rotation direction is unusual.

10. M33 (Triangulum Galaxy)

- The Triangulum Galaxy is a smaller spiral galaxy with arms that exhibit a logarithmic spiral structure. It is part of the Local Group, along with the Milky Way and Andromeda.

-

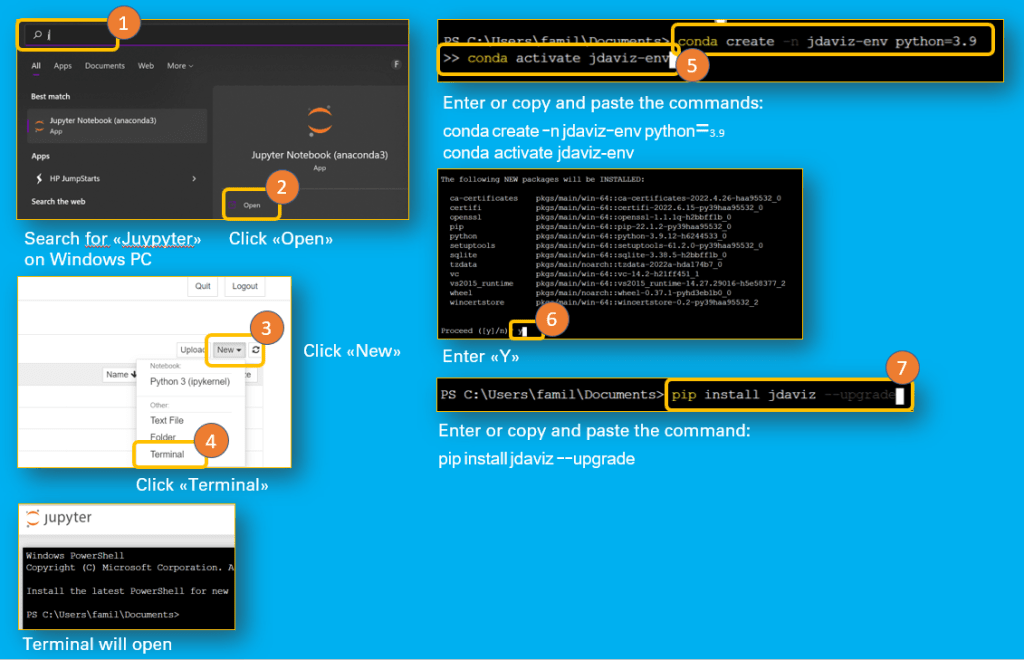

How to Download, View, And Edit Images from the James Webb Space Telescope with Jdaviz and Imviz

Like to comfortably view and edit images from the Jamew Webb Space Telescope like an astronomer ?

Then follow this step by step cheatsheet guides if you are using windows on a PC .

Main Software Components

There are three key software components required:

- Microsoft C++ 14

- Jupyter Notebook (Python)

- Jdaviz

Additonal

- MAST Token to be able to download the images with Imviz.

Prerequsites:

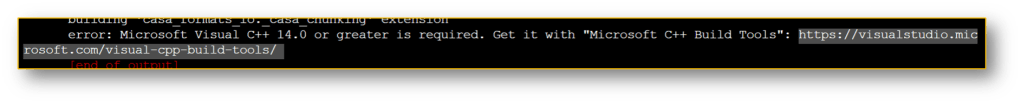

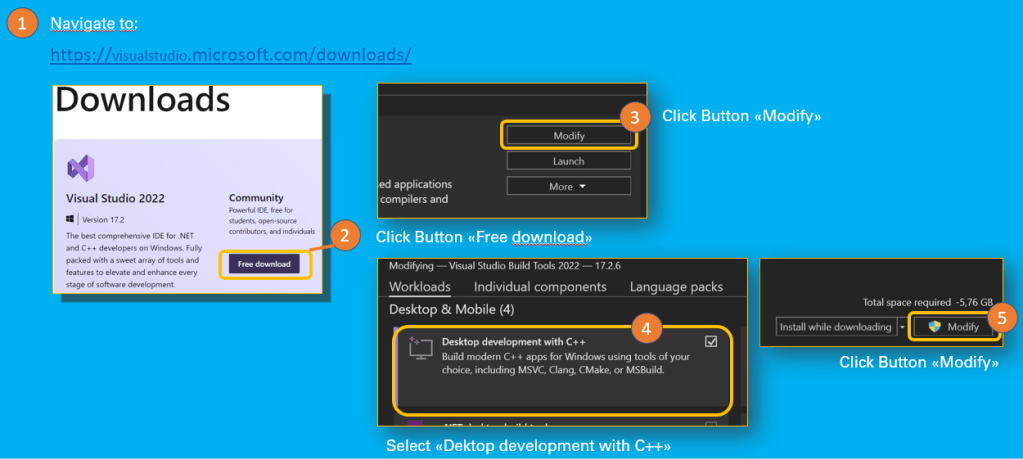

Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater

error: Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater is required If Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater is not installed, the installation of Jdaviz will fail. Without Jdaviz the downloaded images from the James Webb Space Telescope cannot be edited.

How to install Microsoft Visual C++

- Navigate to: https://visualstudio.microsoft.com/downloads/

- Download Visual Studio 2022 Community version

- Follow the instructions in this post: Install C and C++ support in Visual Studio | Microsoft Docs

Cheatsheet: Install Visual Studio 2022 MAST Token

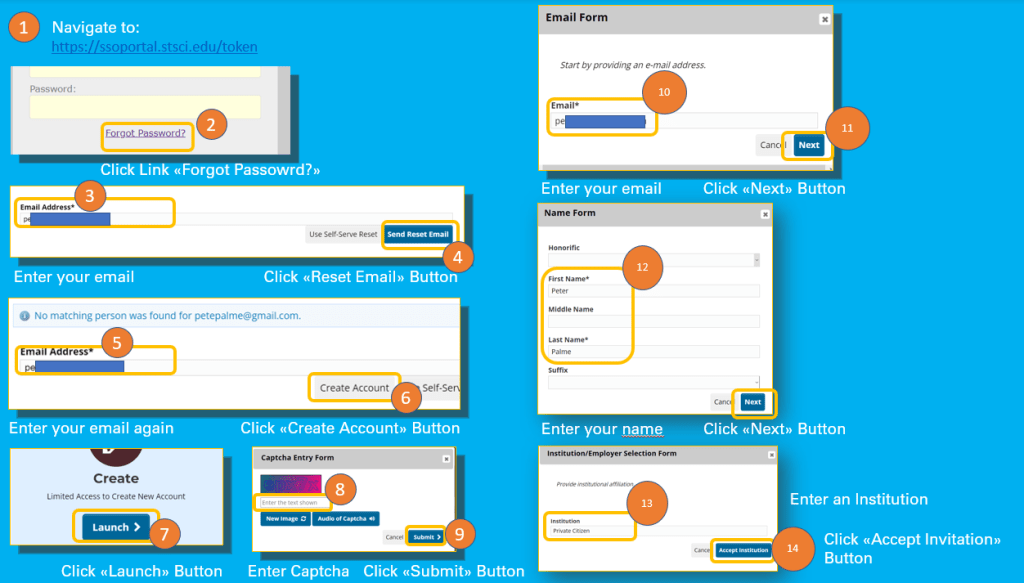

- Navigate to https://ssoportal.stsci.edu/token

If you do not have not an account yet, please follow below steps to create your account:

- Click on the Forgotten Password? link

- Enter your email Adress

- Click Send Reset Email Button

- Click Create Account Button

- Click Launch Button

- Enter the Captcha

- Click Submit Button

- Enter your email

- Click Next Button

- Fill in the Name Form

- Click Next Button

- Fill in the Insitution (e.g. Private Citizen or Citizen Scientist)

- Click Accept Institution Button

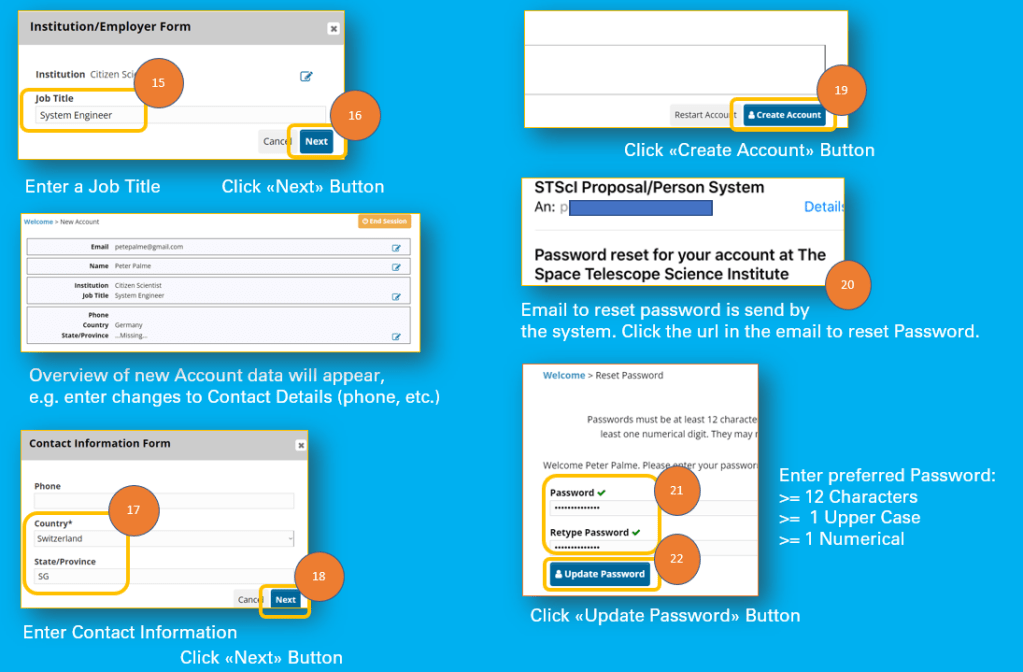

- Enter Job Title (whatever you are or like to be ;-))

- Click Next Button

- New Account Data for your review is presented, in case of missing contact data, step 17 might be necessary

- Fill in Contact Information Form

- Click Next Button

- Click Create Account Button

- In your email account open the reset password emal

- Click on the link

- Enter Password

- Enter Retype Password

- Click Update Password

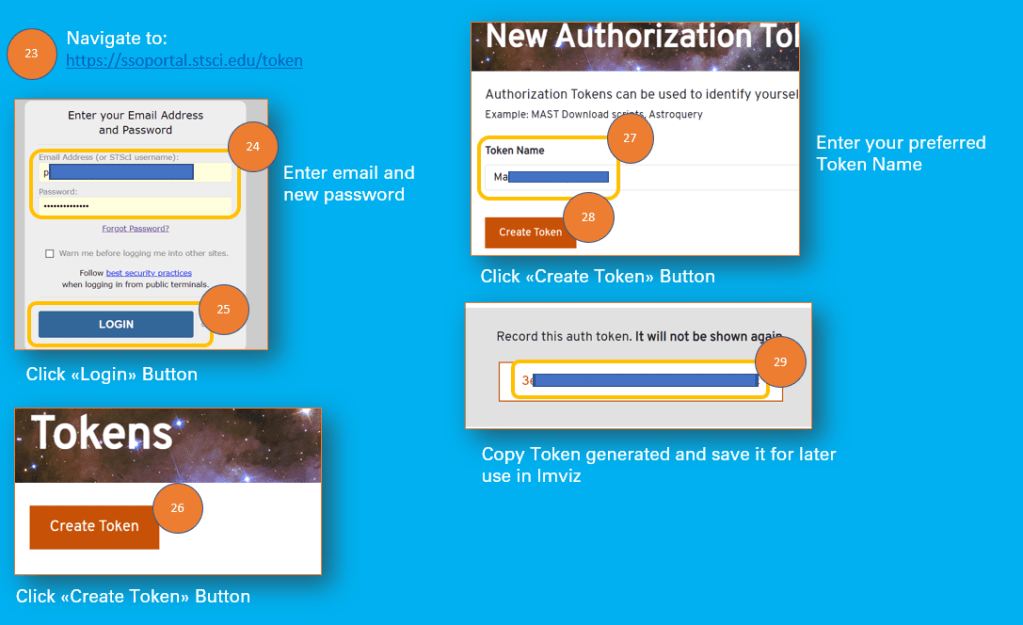

- Navigate to https://ssoportal.stsci.edu/token

- Now log on with your email and new account password

- Click Create Token Button

- Fill in a Token Name of your choice

- Click Create Token Button

- Copy the Token Number and save it for later use in Imviz to download the images from the James Webb Space Telescope

Quite a lot of steps for a Token.

Cheatsheet: Create MAST Account

Cheatsheet: Set Passord for new Account

Cheatsheet: Create MAST Token for use in Imviz Jupyter Notebook

Jupyter notebook comes with the ananconda distribution.

- Navigate to: https://www.anaconda.com/products/distribution#windows

- Follow the instructions at: https://docs.anaconda.com/anaconda/install/windows/

Install Jdaviz

- Navigate to: Installation — jdaviz v2.7.2.dev6+gd24f8239

- Open the Jupyter Notebook

- Open Terminal from Jupyter Notebook

- Follow the instruction in: Installation — jdaviz v2.7.2.dev6+gd24f8239

Cheatsheet: Install Jdaviz How to use IMVIZ

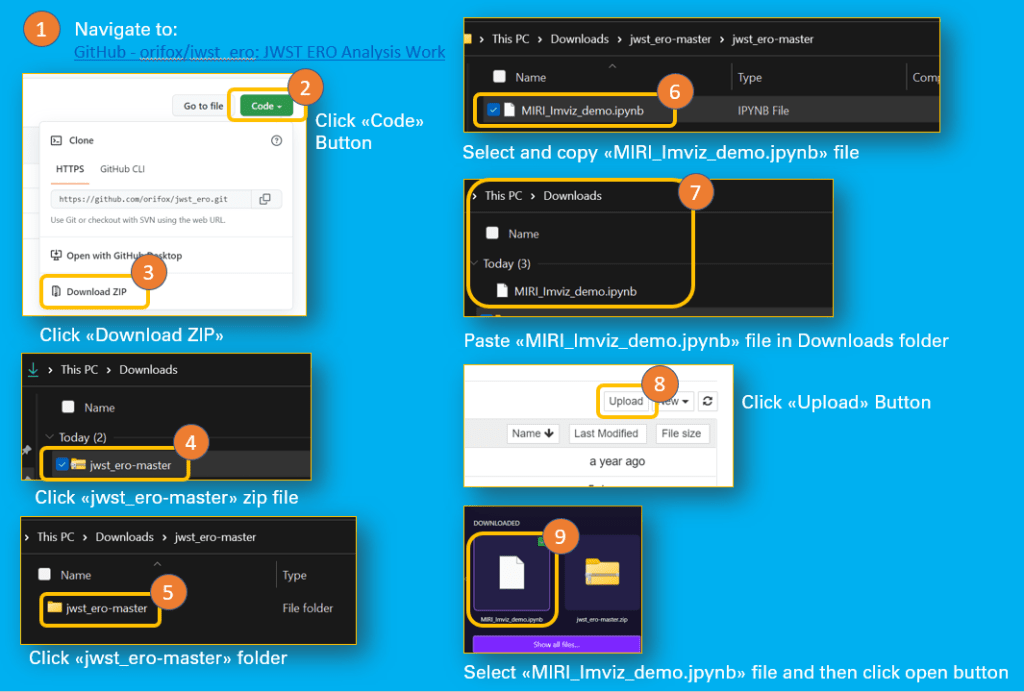

Imviz is installed together with Jdaviz.

Following steps to take in order to use Imviz:

- Navigate to: GitHub – orifox/jwst_ero: JWST ERO Analysis Work

- Click Code Button

- Click Download Zip

- If you do not have unzip, then the next steps might work for you:

- In Download Folder (PC) click the jwst_ero master zip file

- Then click on the folder jwst_ero master

- Copy file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb

- Paste the file in the download folder

- Open Jupyter notebook

- Click Upload Button

- Select the file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb

- Click Open Button

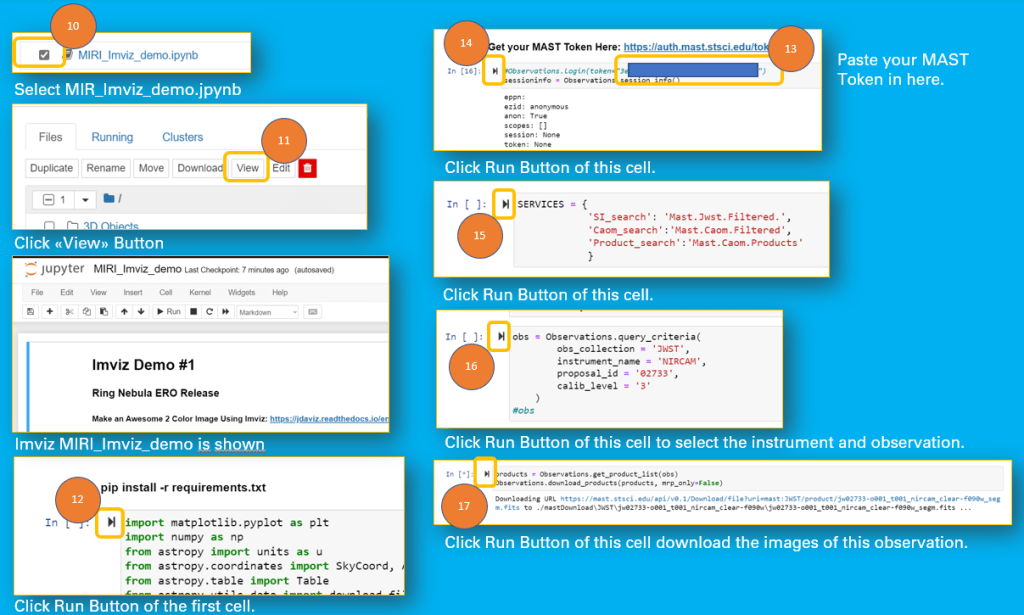

- Select the file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb in the Jupyter Notebook file list

- Click View Button

- Click Run Button First Cell

- Paste MAST Token in next cell

- Click Run Button of this Cell

- Click then Run Button of next Cell

- Click Run Button of the following Cell

- Click Run Button of the next Cell to download the images

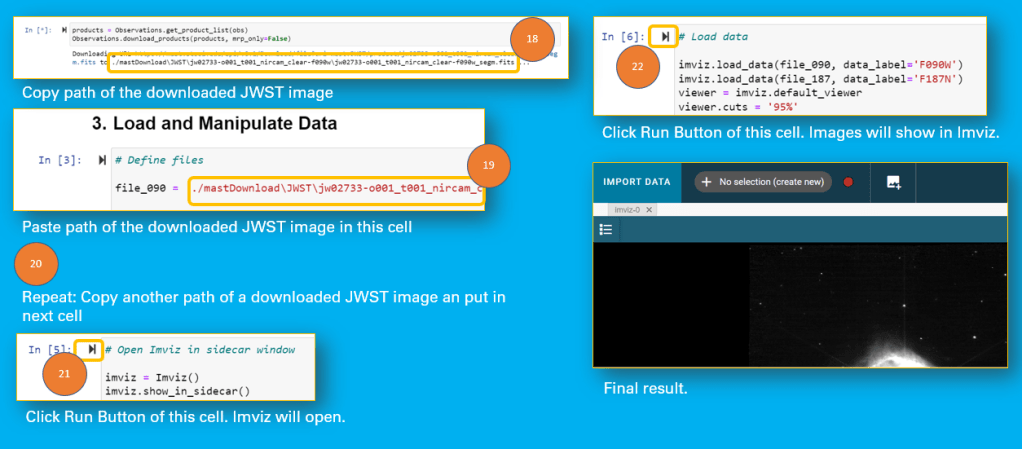

- Copy the link to the downloaded image file

- Past link into the First Cell in 3. Load and Manipulate Data

- Do the same in the next Cell

- Click Run Button of the Cell to open Imviz

- Click Run Button on the next Cell to load images in Imviz

Cheatsheet: Upload MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb in Jupyter notebook Now all set to download the images of the JWST observation:

Cheatsheet: Download JWST images with Imviz And now all is set to open and edit the images in Imviz

Cheatsheet: Open Images in Imviz And finally you are ready to follow the video tutorials in order to learn how to use Imviz to manipulate the JWST images.

Video Tutorials for Imviz:

And this is the master Ori Fox of the Imviz demo notebook file if you like to follow him on Twitter

-

Time for a new scientific debate – Accretion vs Convection

To what degree is gravity needed to form structures in space? While many believe that celestial bodies (stars, planets, moons, meteoroids) can only form through gravitational attraction in the vacuum of space, I believe that these bodies form through a thermodynamic process similar to the formation of hydrometeors (e.g., hail). This is because our solar system possesses a boundary layer, a discovery made by the Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) mission in 2013.

In simple terms: Planets, moons, and small bodies are formed within convection cells created by the jet streams of a young sun, under the influence of strong magnetic fields.

Recently, a new paper introduced quantum models in which gravity emerges from the behavior of qubits or oscillators interacting with a heat bath.

More details and link to the research paper: On the Quantum Mechanics of Entropic Forces

https://circularastronomy.com/2025/10/09/entropic-gravity-explained-how-quantum-thermodynamics-could-replace-gravitons/ -

Accelerating Research Gap Discovery with AI: A Systematic Review of Methods, Tools, and Trends

Researchers have increasingly adopted Artificial Intelligence, using powerful techniques like topic modeling, citation network analysis, and advanced transformer models to automate the laborious process of reviewing scientific literature and discovering research trends.

Summary

Researchers today are confronted with an unprecedented explosion of scientific literature. This deluge of information makes traditional manual literature reviews incredibly time-consuming and often inefficient, risking missed connections and overlooked discoveries. To combat this, the academic community has increasingly turned to Artificial Intelligence (AI), leveraging powerful techniques like Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Machine Learning (ML) to automate the analysis of vast scholarly databases.

However, the initial excitement for AI-driven discovery is now met with a critical complication. Current AI tools, while adept at identifying patterns and summarizing content, are not a panacea. They introduce significant new challenges: many advanced models operate as “black boxes,” making their reasoning opaque; they can inherit and amplify biases present in the training data, potentially reinforcing the status quo; and there is a critical lack of standardized methods to evaluate whether the “gaps” they identify are genuine areas for innovation or simply artifacts of an algorithm.

This leads to the central, pressing question guiding the current field: How can the research community move beyond using AI for mere automation and responsibly harness it to accelerate the discovery of true, impactful research gaps while navigating the inherent technical and ethical complexities?

Researchers today are confronted with an unprecedented explosion of scientific literature. This deluge of information makes traditional manual literature reviews incredibly time-consuming and often inefficient, risking missed connections and overlooked discoveries. To combat this, the academic community has increasingly turned to Artificial Intelligence (AI), leveraging powerful techniques like Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Machine Learning (ML) to automate the analysis of vast scholarly databases.

A 5-Step Guide to Finding Research Gaps with AI

This process is designed as a human-AI partnership. Your critical thinking is the most important ingredient; AI is the catalyst that dramatically speeds up the process.

Step 1: Define Your “Seed” (The Human Start)

Before you can leverage AI, you need to give it a starting point. AI tools can’t read your mind; they need a well-defined direction.

- Action: Clearly define your broad area of interest. Don’t worry about it being perfect.

- Find Seed Papers: Identify 1 to 3 highly relevant, foundational papers in this area. These are your “seed papers” that you will plant in the AI tools. A great seed paper is often a highly cited review article or a seminal study.

Pro-Tip: Your goal here isn’t to be an expert, but to have a clear enough topic to guide the AI search.

Step 2: Map the Universe (The Macro View)

Now, let’s use AI to see the entire research landscape from a 10,000-foot view. This step uses citation network analysis to show you how ideas and papers connect.

- Action: Go to a tool like Litmaps, Connected Papers, or ResearchRabbit.

- Upload Your Seed Papers: Input the titles or DOIs of the seed papers you identified in Step 1.

- Analyze the Map: The tool will generate a visual network of papers. Look for:

- Clusters: Dense groups of interconnected papers. These are the major, well-established sub-fields or conversations.

- White Spaces: Areas with few connections between major clusters. These are potential “bridging gaps” where different sub-fields could be linked.

- Seminal Papers: Papers with many lines pointing to them. These are the foundational works you must know.

Step 3: Discover the Key Conversations (The Thematic View)

You now have a map of papers, but what are they all talking about? This is where topic modeling and semantic analysis come in.

- Action: Use an AI research assistant like Elicit or the summarization features within other tools.

- Ask Broad Questions: Pose questions like, “What are the main themes in the literature on [your topic]?” or “Summarize the key findings from these papers.”

- Identify Themes: The AI will read the abstracts of dozens or hundreds of papers and group them into recurring themes. Pay attention to:

- Dominant Themes: What are the most common topics? This is the core of the field.

- Emerging Themes: Are there new, smaller themes popping up in recent years? These could be the next big thing.

Step 4: Hunt for the Gaps (The Micro View)

With the landscape mapped and themes identified, you can now zoom in to find specific gaps. A research gap isn’t just a topic that hasn’t been written about; it’s often a limitation, contradiction, or an unanswered question.

- Action: Use your AI tools to ask targeted questions about the literature you’ve gathered.

- Look for Limitations: Ask, “What are the limitations of [a specific methodology]?” or “What are the unresolved questions in [a specific theme]?” AI is excellent at scanning papers for sections titled “Limitations” or “Future Work.”

- Find Contradictions: Ask, “What are the conflicting findings regarding [your topic]?” Debates in the literature are a goldmine for research gaps.

- Explore New Contexts: Think about the themes you found. Has a dominant theme in one cluster been applied to another? For example, “Has [Method A] been used to solve [Problem B] in the context of [emerging theme C]?”

Step 5: Validate and Refine (The Final Human Check)

The AI has given you a list of potential gaps. Your final, crucial role is to use your human intellect to validate them.

- Action: For the 1-3 most promising gaps you’ve identified, read the key papers yourself. The AI gets you to the right papers faster, but it can’t replace your critical understanding.

- Ask Critical Questions:

- Is this gap real, or did I misunderstand the literature?

- Is this gap significant? Is it worth solving?

- Is it feasible for me to address this gap with my resources and skills?

By following this workflow, you combine your unique human insight with the raw processing power of AI, turning a months-long process into a matter of days or weeks.

academic research, academic writing, ai, AI in research, artificial intelligence, automated literature review, bibliometric analysis, education, grad school, how to find a research gap, knowledge discovery, Literature Review, machine learning, natural language processing, NLP, PhD life, research gap, research innovation, research methodology, research tools, science mapping, systematic review, technology, writing -

The 9:1 Battle for Time: The Operational Framework and the Dual-Anonymous System that Selects the Universe’s Next Great Discoveries

Summary, Step-by-Step Guide to JWST Proposal Success, and Comprehensive Proposal Checklist

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) was designed with multiple, complementary access policies—primarily the General Observer (GO) program (open competition), the Guaranteed Time Observations (GTO) (rewarding instrument developers with about 16% of the first three cycles), and Director’s Discretionary Time (DDT) (reserved for time-critical events or exceptional urgency)—AND these policies were implemented using a rigorous, bias-mitigating Dual-Anonymous Peer Review (DAPR) system with clear evaluation criteria, successfully delivering groundbreaking initial science across core themes like high-redshift galaxy formation and exoplanet atmospheric chemistry.

Summary

The launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) provided the astronomical community with a revolutionary, but finite, resource capable of unlocking the universe’s most profound secrets, from the first galaxies to the atmospheres of exoplanets. Access to this time is managed by the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) through well-defined, multi-faceted policies, including the competitive General Observer (GO) program, the legacy Guaranteed Time Observations (GTO) for instrument builders, and the opportunistic Director’s Discretionary Time (DDT). The selection process relies on the stringent, bias-mitigating Dual-Anonymous Peer Review (DAPR) system, judged on three core criteria: In-field Impact, Out-of-field Impact, and Feasibility.

Despite these rigorous policies, the sheer scientific ambition of the global community has led to unprecedented demand, with recent proposal cycles (e.g., Cycle 4) receiving over 2,300 submissions and generating a persistent ≈9:1 oversubscription rate (by requested hours). This hyper-competitive environment has strained the traditional review process by dramatically increasing the workload on the Time Allocation Committee (TAC) and challenging the efficacy of the original proposal structure and science categories, threatening the long-term sustainability and fairness of the system.

How is the JWST time allocation system evolving its policies and procedures—particularly in response to severe oversubscription—to maintain efficiency, fairness, and maximize the revolutionary scientific return across key research themes?

In response to challenges documented by the JWST Users Committee (JSTUC), the system is demonstrating rapid and concrete policy adaptation. Key changes introduced in Cycle 4 (and continuing into future cycles) include:

- Process Efficiency: Reducing proposal page limits by nearly 50% to lessen TAC burden.

- Targeted Science: Restructuring the Science Categories to better align with JWST’s unique breakthrough areas, such as High-Redshift Galaxies and Exoplanet Atmospheres.

- Increased Capacity: Substantially increasing the total allocated hours (e.g., from ≈5,500 in Cycle 3 to ≈8,500 in Cycle 4) to absorb some of the immense demand.

The literature review shows that the system is not static; it is actively adjusting its mechanics to ensure that the scientific breakthroughs—like the papers by Oesch & Adamo (2025) rewriting cosmology and the Wakeford/Ohno teams characterizing exoplanet chemistry—continue to be selected and executed efficiently.

Based on the structured literature review, here is a step-by-step guide for a new astronomer to maximize the value of this information and significantly improve their chances of winning highly competitive James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) observation time.

Step-by-Step Guide to JWST Proposal Success

Phase 1: Understand the Battlefield (The 9:1 Challenge)

The core finding of the review is the sheer intensity of the competition: the oversubscription rate is roughly 9:1 (90% of requested hours are rejected). You must aim not just for “good” science, but for “transformative” science.

- Acknowledge the Competition (≈9:1): Immediately discard the idea of submitting a “safe” or incremental proposal. Your proposal must target a Grade 1: Transformative score, meaning its potential scientific return would fundamentally rewrite a field of study.

- Define Your Program Type:

- General Observer (GO): This is the standard, competitive route (the bulk of the time). Focus on small programs, as they are often easier to schedule.

- Director’s Discretionary Time (DDT): Only pursue this if your target is truly urgent (e.g., a newly detected supernova, a rapidly fading transient). Do not use DDT to bypass the GO program.

- GTO: This time is no longer being allocated for new groups (it was reserved for instrument developers), so focus your strategy on GO programs.

- Benchmark Against Key Themes: Your topic should align with or advance the most successful current themes. The review highlights:

- High-Redshift Galaxies and the Distant Universe (Rewriting cosmology).

- Exoplanet Atmospheres and Habitability (Detailed chemical characterization).

- Focus your science on unique JWST capabilities (mid-infrared, high sensitivity).

Phase 2: Master the Evolving Procedure

The system is adaptive. Success requires adherence to the newest, strictest policies, many of which were introduced to cope with the high submission volume.

- Strictly Follow Cycle 4/5 Rules (Policy Adaptation): The review emphasized that proposal page limits were halved and new categories were introduced.

- Conciseness is Critical: Learn to write your scientific justification in the reduced page count. Every sentence must maximize impact.

- Align with New Categories: Ensure your proposal fits precisely into the newly restructured Science Categories (e.g., Exoplanet Atmospheres) to ensure it reaches the right specialized panel.

- Focus Solely on Scientific Merit (Dual-Anonymous Peer Review – DAPR): The system is designed to judge the idea, not the person.

- Scientific Justification: This must be impeccable. Do not include any identifying information (names, institutions, specific publication references that only your team could write) in the science section.

- Evaluation Criteria: Structure your proposal content around the three core TAC criteria: In-field Impact, Out-of-field Impact, and Suitability & Feasibility. Address each one explicitly.

- Team Expertise: Your team’s qualifications are only reviewed after the proposal is scientifically ranked. Win on the science first.

- Verify Technical Feasibility: The technical justification must be sound. Use the Exposure Time Calculator (ETC) meticulously. Any technical flaw will be grounds for immediate rejection, regardless of scientific merit.

Phase 3: Writing for the TAC and Maximizing Impact

- Emphasize “Out-of-Field Impact”: Since the TAC uses this as a key ranking criterion, clearly explain how your niche observation will impact a broader field (e.g., observing a single protoplanetary disk doesn’t just impact planet formation, it constrains disk chemistry models relevant to stellar evolution).

- Structure Your Narrative (ABT Framework): Use the And–But–Therefore (ABT) structure to tell a concise story:

- AND: (The current state of knowledge is X).

- BUT: (JWST’s unique capability is needed to resolve the critical flaw/gap Y in knowledge X).

- THEREFORE: (This observation will lead directly to the transformative result Z).

- Use STScI Reports as Your Guide (JSTUC): Access the JWST Users Committee (JSTUC) Reports and official STScI policy documents. These are the sources that critique the system and announce future policy changes. They provide the most authoritative insight into what the TAC and the Director are prioritizing.

By following these steps, you shift your mindset from merely submitting a proposal to strategically competing within a rapidly evolving, high-stakes system, dramatically increasing the potential value of your submission.

Comprehensive Proposal Checklist for JWST (or Similar Observatories)

1. Understand the Program Structure

- [ ] Identify the correct program type:

- General Observer (GO)

- Guaranteed Time Observations (GTO)

- Director’s Discretionary Time (DDT or DD-ERS)

- [ ] Confirm eligibility and submission windows for the selected program.

2. Align with Proposal Size Categories

- [ ] Choose the appropriate size category:

- Very Small (≤20 hrs)

- Small (>20–50 hrs)

- Medium (>50–130 hrs)

- Large (>130 hrs)

- [ ] Be aware of oversubscription rates (e.g., Medium proposals face the highest competition at 11.4:1)[1].

3. Follow Dual Anonymous Peer Review (DAPR) Guidelines

- [ ] Do not include any identifying information:

- No names, institutions, prior work, or funding sources.

- No mention of team roles (e.g., student, postdoc).

- [ ] Ensure all scientific justification is anonymous and focused on merit.

- [ ] Use the “Team Expertise and Background” section only for post-review visibility.

4. Address the Three Core Evaluation Criteria

- [ ] In-field Impact: Demonstrate transformative potential in your sub-field.

- [ ] Out-of-field Impact: Show broader relevance across astronomy.

- [ ] Suitability & Feasibility:

- Justify why JWST is uniquely required.

- Prove that archival data is insufficient.

- Present a clear, efficient observing plan.

5. Comply with Structural and Formatting Requirements

- [ ] Adhere strictly to page limits (Cycle 4 saw disqualifications for exceeding them).

- [ ] Use concise, high-impact writing to fit within reduced space.

- [ ] Avoid formatting that could hint at identity or affiliations.

6. Optimize for Review Panel Matching

- [ ] Select accurate science categories (e.g., “High-Redshift Galaxies” or “Exoplanet Atmospheres”).

- [ ] Use precise keywords to ensure domain experts review your proposal.

7. Avoid Common Pitfalls

- [ ] Double-check for DAPR violations.

- [ ] Ensure proposal length is within limits.

- [ ] Avoid vague or overly technical justifications that lack clarity under anonymity constraints.

8. Strategic Considerations

- [ ] Consider submitting Medium-sized proposals with extra care due to high competition.

- [ ] Leverage early access programs (e.g., DD-ERS) if applicable.

- [ ] Monitor policy updates (e.g., Cycle 5 may adjust Medium program allocations and DAPR guidance).

References

Astronomical Observation, astronomy, astrophysics, books, Cosmology, DAPR, DDT, Dual-Anonymous Peer Review, Exoplanet Atmospheres, GO Program, GTO, High-Redshift Galaxies, James Webb Space Telescope, JSTUC, JWST, JWST Cycle 4, JWST Cycle 5, JWST Observation Time, JWST Proposal Process, JWST Proposal Success, Oversubscription, Peer Review, photography, physics, science, Science Policy, STScI, Telescope Time Allocation, Webb Telescope -

Entropic Gravity Explained: How Quantum Thermodynamics Could Replace Gravitons

Impact on Spaceflight Operations

For decades, physicists have understood fundamental forces like electromagnetism and gravity as being mediated by quantum fields and virtual particles, such as photons and gravitons. At the same time, some forces in nature—like pressure in a gas—emerge not from fundamental interactions but from thermodynamic principles, driven by entropy and free energy.

We’re taught that gravity is a fundamental force, like electromagnetism, and that it’s carried by hypothetical particles called gravitons. This is the standard view in physics, especially in quantum gravity research.

But what if gravity isn’t fundamental at all? What if it’s more like pressure in a gas—something that emerges from the collective behavior of microscopic systems trying to reach thermal equilibrium? This idea, called entropic gravity, has been around for a while, but until now, it lacked a solid quantum foundation.

Can we build a fully quantum model where gravity emerges from entropy and thermodynamics, rather than from fundamental particles like gravitons? And if so, how would we test it?

Yes—and that’s exactly what this paper does. The authors construct detailed quantum models where gravity arises from the behavior of qubits or oscillators interacting with a heat bath. These systems naturally produce a force that looks like Newton’s law of gravity—not because of graviton exchange, but because the system is trying to minimize its free energy. Even better, the models predict subtle differences from standard gravity, like tiny amounts of noise and decoherence, which could be detected in near-future experiments.

On the Quantum Mechanics of Entropic Forces

Daniel Carney1,*, Manthos Karydas1, Thilo Scharnhorst1,2, Roshni Singh1,2, and Jacob M. Taylor

https://journals.aps.org/prx/abstract/10.1103/y7sy-3by1

Impact on Spaceflight Operations

In the entropic gravity framework described in the paper, gravity emerges from the thermodynamic behavior of a mediator system (like qubits or oscillators) interacting with massive bodies. Therefore, entropic gravity can decrease when conditions reduce the entropy gradient or disrupt the thermal equilibrium that drives the force.

Factors That Decrease Entropic Gravity

- Lower Temperature of the Mediator System (T):

- The entropic force is proportional to ( T^2 ), so reducing the temperature directly weakens the force: $ F_{\text{entropic}} \propto T^2 $

- In cold environments or cryogenic conditions, the entropic contribution to gravity becomes smaller.

- Reduced Coupling Between Masses and Mediators:

- If the interaction between the masses and the mediator system weakens (e.g., smaller coupling constants like ( l )), the entropy gradient becomes less sensitive to mass positions.

- This leads to a weaker entropic force.

- Increased λ Parameter (Nonlocal Model):

- In the nonlocal model, the function ( f(x) ) includes a term: $ \frac{1}{f(x)} = \lambda + \frac{l^2}{|x|} $

- A large λ suppresses the position-dependent part of the force, effectively reducing entropic gravity.

- Disruption of Thermal Equilibrium:

- Entropic gravity relies on the mediator system being in thermal equilibrium.

- Rapid motion (e.g., fast acceleration, rotation, or vibration) can push the system out of equilibrium, reducing the entropic force temporarily or introducing noise.

- Sparse or Low-Density Mediator System:

- Fewer qubits or oscillators mean less entropy to drive the force.

- In the local model, increasing the lattice spacing ( a ) reduces the density of mediators, weakening the gravitational interaction.

- Chemical Potential Tuning (Local Model):

- Specific values of the chemical potential ( \mu ) can suppress the internal energy contribution, and in some regimes, reduce the overall force.

- Quantum Decoherence or Noise:

- If the mediator system becomes noisy or decoheres due to environmental interactions, the entropic force may become less coherent or weaker.

Summary

Entropic gravity decreases when:

- The system is colder,

- The coupling is weaker,

- The mediator is sparse or poorly thermalized,

- The λ parameter dominates over position dependence,

- The system is driven far from equilibrium.

🌀 Does Rotation Reduce Entropic Gravity?

Short answer: Not directly—but it can affect the local thermodynamic conditions that determine the strength of entropic gravity.

Why Rotation Might Matter in Entropic Gravity

- Thermal Equilibrium Assumption:

- Entropic gravity arises from a mediator system (qubits or oscillators) that must remain in thermal equilibrium.

- Rotation introduces non-equilibrium dynamics (e.g., centrifugal forces, shear, turbulence), which could disturb the mediator system.

- If the system is driven out of equilibrium, the entropic force may decrease or fluctuate, depending on how well the system re-thermalizes.

- Local Entropy Gradients:

- Rotation can redistribute mass and energy, potentially altering local entropy gradients.

- Since entropic gravity is driven by gradients in entropy, this redistribution could change the direction or magnitude of the force.

- Decoherence Effects:

- The paper discusses how spatial superpositions and motion can cause decoherence in the entropic model.

- Rotation might enhance decoherence effects, especially in the local model, where each mass interacts with a lattice of qubits.

- This could lead to additional noise or damping in the gravitational interaction.

- Adiabatic Limit Violation:

- The entropic force assumes slow, adiabatic motion of masses.

- Rapid rotation or thrust changes could violate this assumption, leading to transient deviations from Newtonian gravity.

Summary

- Rotation doesn’t reduce gravity directly, but it can disturb the thermal mediator system that gives rise to entropic gravity.

- This could lead to fluctuations, noise, or reduced force if the system is pushed out of equilibrium.

- In practical terms, for a rocket launch, these effects are likely very small unless the rotation is extreme or the system is engineered to be sensitive to entropic effects.

Rotation is quite common and may be an inherent behavior of objects traveling through space. Perhaps there is another fundamental constant yet to be discovered.

beginner physics, emergent gravity, entropic forces, entropic gravity, gravitational decoherence, gravitational noise, graviton alternative, gravity and entropy, gravity experiments, gravity without gravitons, heat bath models, Newton’s law, physics explained, quantum field theory, quantum gravity, quantum information, quantum mechanics, quantum physics blog, quantum thermodynamics, thermodynamic gravity - Lower Temperature of the Mediator System (T):

-

The Reusable Rocket Revolution: A Comprehensive Guide to the Technology, Economics, and Future of Spaceflight

For decades, the concept of a fully reusable rocket capable of airline-like operations has been the ultimate goal in spaceflight, promising to dramatically lower the cost of accessing orbit, AND with the advent of systems like the Space Shuttle and the modern success of SpaceX’s Falcon 9, the world has proven that recovering and reflying rocket boosters is technologically possible, fundamentally changing the landscape of the global launch industry.

A Novice-to-Expert Guide to Rocket Reusability

For more than 60 years, space exploration has operated on an incredibly expensive and wasteful model. Like throwing away a brand-new airplane after a single flight, rockets worth hundreds of millions of dollars were designed to be used only once, burning up in the atmosphere or crashing into the ocean. This expendable approach made access to space a rare and costly endeavor, limiting what humanity could achieve in orbit and beyond.

This established reality was shattered in the last decade. A revolution, spearheaded by companies like SpaceX with its Falcon 9 rocket, proved that it was possible to fly a rocket’s first stage to space, deliver a payload, and then land that same booster back on Earth for reuse. This breakthrough has dramatically changed the launch industry. However, this success created a new, complex set of problems. The literature shows that simply catching the booster is not enough. The dream of “fully and rapidly” reusable rockets faces immense hurdles: the cost and time for refurbishment are still very high, and the technology to recover the much faster, hotter-reentering second stage (the part of the rocket that actually goes into orbit) does not yet exist. We have solved only part of the puzzle.

This leads to the central question that defines the entire field of modern astronautics: Now that we know partial reusability is possible, what are the specific technologies, economic models, and future innovations required to overcome the current barriers and achieve the ultimate goal of a fully and rapidly reusable space launch system?

The literature provides a clear, multi-layered answer. Achieving the reusability revolution requires progress on three critical fronts simultaneously:

- Perfecting First-Stage Economics: The immediate focus is on mastering the logistics of the existing technology. This means driving down refurbishment costs, speeding up turnaround times from weeks to days, and developing materials that can withstand the stress of multiple flights without extensive repairs.

- Solving the Second-Stage Challenge: This is the next great technological frontier. The answer lies in developing breakthrough technologies like ultra-lightweight, durable heat shields to survive fiery reentry, mastering on-orbit refueling to allow a second stage to de-orbit itself, and designing engines that can reliably restart in the vacuum of space multiple times.

- Broadening the Methods: The research shows that SpaceX’s propulsive landing isn’t the only answer. The future likely involves a mix of strategies tailored to different rockets, including mid-air capture for smaller boosters (pioneered by Rocket Lab) and winged, spaceplane-like horizontal landings for others (being explored by European agencies).

In short, the journey from today’s partially reusable rockets to a future of affordable, airline-like access to space depends on a combination of improving today’s methods, inventing tomorrow’s technology, and staying open to diverse solutions.

aerospace engineering, Ariane Next, Blue Origin, cost of space launch, economics of space, Falcon 9, first-stage recovery, future of spaceflight, launch vehicle recovery, nasa, New Glenn, news, propulsive landing, rapid turnaround launch, reusable launch vehicle, reusable rockets, rocket reusability, second-stage reusability, space, space exploration, space launch systems, space policy, space technology, SpaceX, Starship, sustainable space, technology, Themis -

The AI-Thermodynamics Revolution: Accelerating Scientific Discovery and Engineering a Sustainable Future

The application of Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly Machine Learning (ML), has demonstrated remarkable success in thermodynamics, enabling the development of highly accurate and efficient models for molecular simulation, materials design, and property prediction. Pioneering work, such as the creation of High-Dimensional Neural Network Potentials (HDNNPs) by Behler and Parrinello [1] and the subsequent rise of Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs), has allowed for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to achieve near-quantum accuracy at classical computational scales, rapidly advancing the prediction of thermodynamic properties.

The core laws of thermodynamics govern nearly every process in nature and engineering, from energy storage to materials synthesis. The rise of Machine Learning (ML) has offered an unprecedented opportunity to accelerate this field. Early models, exemplified by Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) like the High-Dimensional Neural Network Potentials (HDNNPs) [1], have already proven capable of providing quantum-level accuracy at classical speeds for molecular simulations, representing a massive leap in predictive modeling capability.

Despite initial triumphs, data-driven AI models faced a critical hurdle: they often acted as “black boxes” that violated the very physical laws they were meant to model. This resulted in a “consistency crisis,” where ML predictions failed to uphold fundamental Maxwell relations and were prone to catastrophic failure when applied outside their training domain (poor extrapolation). Furthermore, a major theoretical gap exists in applying AI to Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics (NET), the science governing complex, real-world dynamic processes.

How can the power of AI be harnessed to accelerate thermodynamic discovery without sacrificing the physical rigor and consistency required for robust scientific and engineering applications? Specifically, how can researchers embed the principles of thermodynamics into AI models to guarantee physical law adherence, enhance model interpretability, and finally tackle the complex challenges of non-equilibrium dynamics?

Physics-Informed and Thermodynamics-Inspired AI

The literature points toward a decisive shift from purely data-driven models to Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) and Thermodynamics-Inspired AI. Key solutions include:

- Guaranteed Consistency: Developing models like the Free Energy Neural Network (FE-NN), which use Automatic Differentiation (AD) to explicitly model the free energy potential, ensuring all Maxwell relations and the laws of thermodynamics are mathematically preserved [3].

- Enhanced Interpretability: Applying thermodynamic concepts, such as Interpretation Entropy [4], to explain the decisions of complex ML models, turning black boxes into more transparent tools.

- The Future Frontier: Integrating the foundational mathematical principles of Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics (NET) with modern generative models (like Diffusion Models) to build the next generation of AI capable of mastering dynamic, complex systems and accelerating materials and energy discovery [5].

This evolution represents a synthesis: the computational speed of AI is now being married to the unshakable laws of physics, paving the way for trustworthy, universal, and high-impact thermodynamic modeling.

References:

[1] J. Behler and M. Parrinello, “Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 98, no. 14, p. 146401, 2007.

[3] D. G. Rosenberger, K. M. Barros, T. C. Germann, and N. E. Lubbers, “Machine learning of consistent thermodynamic models using automatic differentiation,” Phys. Rev. E, vol. 105, no. 4, p. 045301, 2022.

[4] S. Mehdi and P. Tiwary, “Thermodynamics-inspired explanations of artificial intelligence,” Nat. Commun., vol. 15, no. 1, p. 7752, 2024.

[5] J. Sohl-Dickstein, E. Weiss, J. Maheswaranathan, and S. Ganguli, “Deep unsupervised learning using nonequilibrium thermodynamics,” Proc. Annu. Conf. Mach. Learn. Res., vol. 37, pp. 2256–2265, 2015.ai, AI literature review, AI materials science, AI thermodynamics, artificial intelligence, computational thermodynamics, deep learning in chemistry, free energy models, future of thermodynamics, generative models, machine learning force fields, materials design, MLFF, molecular simulation, NET, Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics, philosophy, physics-informed neural networks, PINNs, science, technology, thermodynamic consistency -

Rayleigh-Bénard and Beyond: A Comprehensive Multiscale Review of Convection Cell Dynamics in Natural and Engineered Systems

Summary: Convection Cells – From Fundamental Physics to Global Systems

This literature review provides a comprehensive, cross-disciplinary synthesis of

dynamics, establishing thermal convection as a foundational mechanism governing heat and mass transport across scientific domains—from planetary interiors to sub-millimeter engineered flows.

Core Theoretical Evolution and Debate

The field is fundamentally rooted in the

model, defined by the dimensionless

and

numbers.

- The Transition to Turbulence: The core focus of modern fluid dynamics is the behavior of convection in the

(high

). Key research by

and

defined the scaling laws relating the Nusselt number (

, a measure of heat transfer efficiency) to

, driving the quest for the theoretical

of heat transfer—a major ongoing debate and research gap.

- The Non-Classical Challenge: Future research is centered on

, including the effects of rotation (

) crucial for geophysical flows, and the influence of complex boundaries and phase changes.

Key Findings and Conflicting Viewpoints Across Domains

Domain Key Mechanism/Model Seminal Finding/Ongoing Debate Geophysics Mantle Convection

The historical debate between is resolving toward a complex model where deep subduction (whole-mantle flow) coexists with chemical and thermal layering, complicating the mechanism of

.

Meteorology Atmospheric Circulation (Hadley, Ferrel Cells)

The failure of the and the need to accurately parameterize

and

in climate models represents the single largest bottleneck in predicting future climate scenarios.

Astrophysics Stellar Convection Zone

The shift from the simplistic to high-fidelity

in numerical models is essential for accurately determining stellar structure and evolutionary tracks.

Gaps and Future Research Directions

The current literature points to two critical avenues for future research:

- Ultimate Regime Experimentation: Designing and executing experiments capable of reaching and confirming the predicted

in extremely high

turbulent convection.

- Multiphysics and Non-Classical Systems: Developing robust models for convection cells under combined influences, such as rotation, magnetic fields, non-Newtonian fluids, and internal heating—essential for advancing real-world applications in

and

.

- The Transition to Turbulence: The core focus of modern fluid dynamics is the behavior of convection in the

-

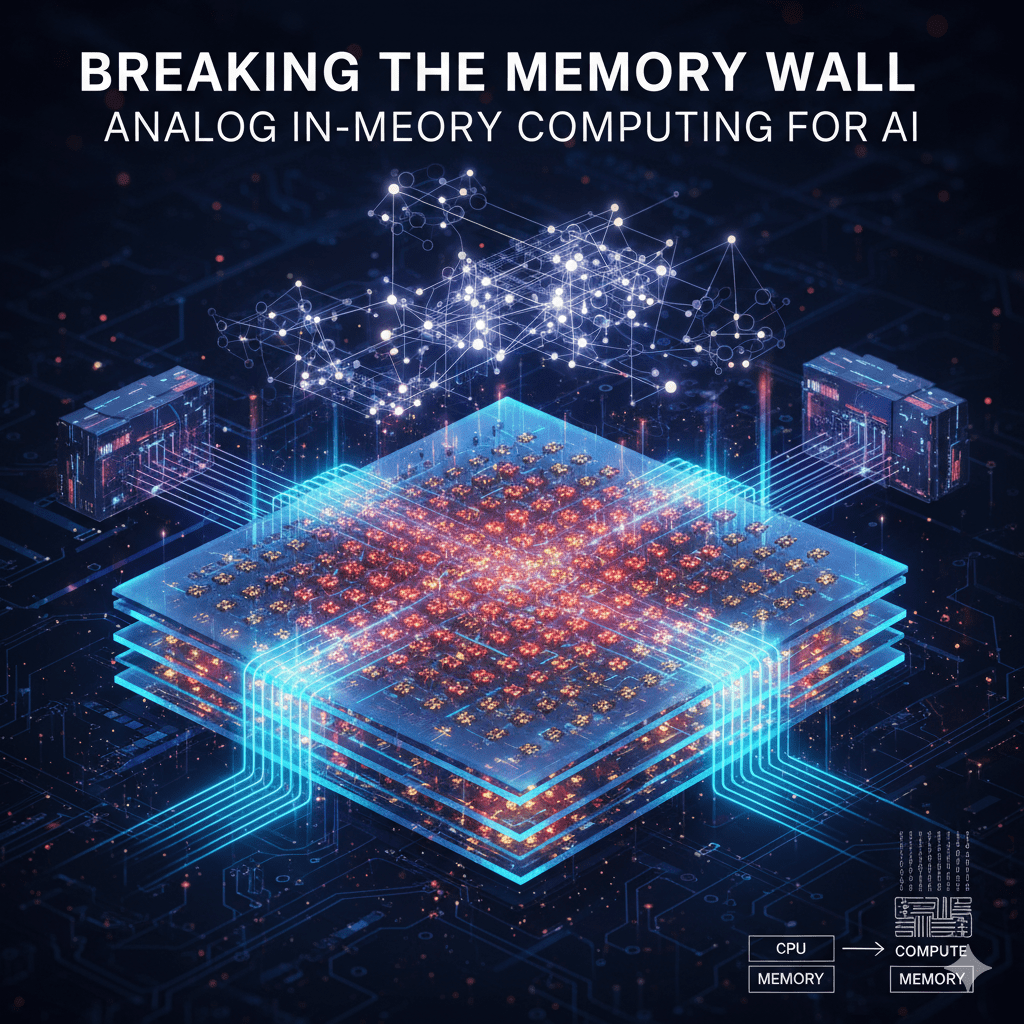

Breaking the Memory Wall: A Structured Literature Review of Analog In-Memory Computing (AIMC) for Next-Generation AI and Deep Learning

Executive Summary: Analog In-Memory Computing (AIMC)

This structured literature review establishes the crucial role of Analog In-Memory Computing (AIMC) as the leading architectural solution to overcome the fundamental von Neumann bottleneck that limits the performance and energy efficiency of modern Artificial Intelligence (AI) hardware.

AIMC integrates computation directly within non-volatile memory (NVM) arrays, leveraging the physical properties of devices like Resistive RAM (RRAM) and Phase-Change Memory (PCM) to perform massively parallel Matrix-Vector Multiplication (MVM) in the analog domain.

Theme Key Findings & Expert Insights Historical Evolution The field’s progression is defined by material science, beginning with Leon Chua’s 1971 memristor theory and accelerating dramatically after the 2008 realization of the memristor. The evolution has shifted from conceptual frameworks to practical integration of NVM arrays as computational crossbar elements. Pioneering Studies Recent seminal work demonstrates AIMC’s practical viability. Breakthroughs include the use of 3D AIMC architectures for accelerating dynamic weights in complex Transformer and Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models [Bu¨chel et al., 2025] and the development of memristor-based nonlinear sorting systems for data-intensive processing [Yuchao et al., 2025]. These studies validate AIMC’s potential for high-efficiency AI acceleration. Ongoing Debates & Challenges The core debate centers on the precision-efficiency trade-off. While analog computation offers superior power efficiency and parallelism, it inherently suffers from device non-idealities (e.g., programming variability, noise, limited endurance) when compared to digital precision. Manufacturing challenges related to high-yield, large-scale 3D integration remain a significant hurdle. Gaps & Future Directions Future research must prioritize the development of hybrid digital-analog architectures to mitigate analog inaccuracies while maintaining efficiency. Critical gaps include creating robust hardware-aware training toolchains and programming models, as well as advancing thermal and power management solutions for dense 3D AIMC chips. The next phase of AIMC development requires a holistic, co-design approach involving device physics, circuit design, and machine learning algorithms. AIMC represents not merely an incremental improvement but a paradigm shift, positioning it as the indispensable backbone for sustainable, high-performance computing at the edge and in the data center.

AI Acceleration, AI Hardware, AIMC, Analog AI, Analog In-Memory Computing, Computer Architecture, Deep Learning Hardware, Edge AI, Energy Efficiency, Hardware-Aware Training, IMC, In-Memory Computing, Literature Review, Memristor, Neuromorphic Computing, Non-Volatile Memory, NVM, PCM, PIM, Processing-in-Memory, Research Gaps, RRAM, Semiconductor Technology, Von Neumann Bottleneck -

Artificial Intelligence in Fluid Dynamics: A Literature Review of Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions

Summary

Decoding Fluid Dynamics: How AI is Redefining Computational Science

The study of fluid dynamics (FD) is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from traditional Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) to a new paradigm powered by Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML). This shift is not merely an optimization of existing methods but a fundamental change in how we discover, simulate, and control complex flows.

The central narrative is the evolution toward hybrid models that blend the best of both worlds: the predictive power of neural networks and the rigorous conservation principles of classical physics.

Key Research Themes and Core Findings

Research Theme Core AI Technique Landmark Finding Significance Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) Deep Learning, Neural Solvers PINNs use the governing equations (e.g., Navier-Stokes) as a loss function, enforcing physical consistency a priori. Allows for data-sparse solutions and model-free discovery of fluid properties, especially in unsteady flows. Turbulence Modeling Neural Networks (NNs), LLMs AI corrects the deficiencies of traditional models (like RANS), with NNs learning the unresolved stresses or even developing models from scratch. Crucially enhances the accuracy and speed of simulations in high-Reynolds number flows, where traditional methods struggle. Flow Control Reinforcement Learning (RL) RL agents learn optimal, active strategies (e.g., using jets or flaps) to reduce drag or noise in real-time, often outperforming human-engineered controllers. Enables autonomous flow optimization, moving the field toward smart, adaptive aerospace and hydraulic systems. Simulation Acceleration Convolutional NNs, Autoencoders ML models can serve as fast surrogate models that predict fine-scale flow fields from coarse-grid inputs or dramatically accelerate time integration. Offers massive computational speedups (up to 103 to 104 times faster than high-fidelity CFD) for iterative design and analysis [Kochkov et al., 2021]. Ongoing Debates and Critical Challenges

The revolutionary promise of AI in FD is tempered by critical, ongoing debates that define the current research frontier:

- The “Black-Box” Problem (Interpretability): The biggest roadblock to engineering adoption is the inherent complexity of deep learning models. Engineers need to know why a design works. Research in Explainable AI (XAI) is vital to connect model predictions back to fundamental fluid mechanics principles [Cremades et al., 2024].

- Generalization and Extrapolation: Data-driven models often fail when applied to flow conditions (e.g., different geometries or Reynolds numbers) outside their training data. The challenge is developing models that can be safely extrapolated and maintain physical fidelity across a wide parameter space.

- Data Requirements: While PINNs are data-sparse, many high-fidelity applications, especially in turbulence, still require massive, expensive datasets (Direct Numerical Simulation – DNS), limiting applications to benchmark problems [Koumoutsakos et al., 2024].

The Frontier: Gaps and Future Research

The most exciting development is the use of AI to address fundamental scientific gaps in the field, moving beyond mere engineering optimization.

- Tackling Fundamental Singularities: The most ambitious research is using AI to explore the mathematical structure of the Navier-Stokes equations, searching for solutions or behaviors that have eluded mathematicians for decades. Google DeepMind (2024) notably used AI to discover new forms of fluid flow singularities, a step toward solving the Millennium Prize Problem [DeepMind Blog, 2024].

- Towards True Hybrid Solvers: Future research must focus on tightly coupling ML components within the CFD loop, not just as pre- or post-processors. This involves developing robust, error-controlled methods that allow the AI to govern only the complex, unresolved physics while the classical solver handles the rest, achieving both speed and physical guarantees.

ai, AI in engineering, artificial intelligence, autonomous simulation, CFD, computational fluid dynamics, DeepMind, engineering research, explainable AI, flow control, fluid dynamics, hybrid models, Literature Review, machine learning, machine-learning, Navier-Stokes, neural solvers, philosophy, physics-informed neural networks, PINNs, scientific computing, technology, turbulence modeling, XAI -

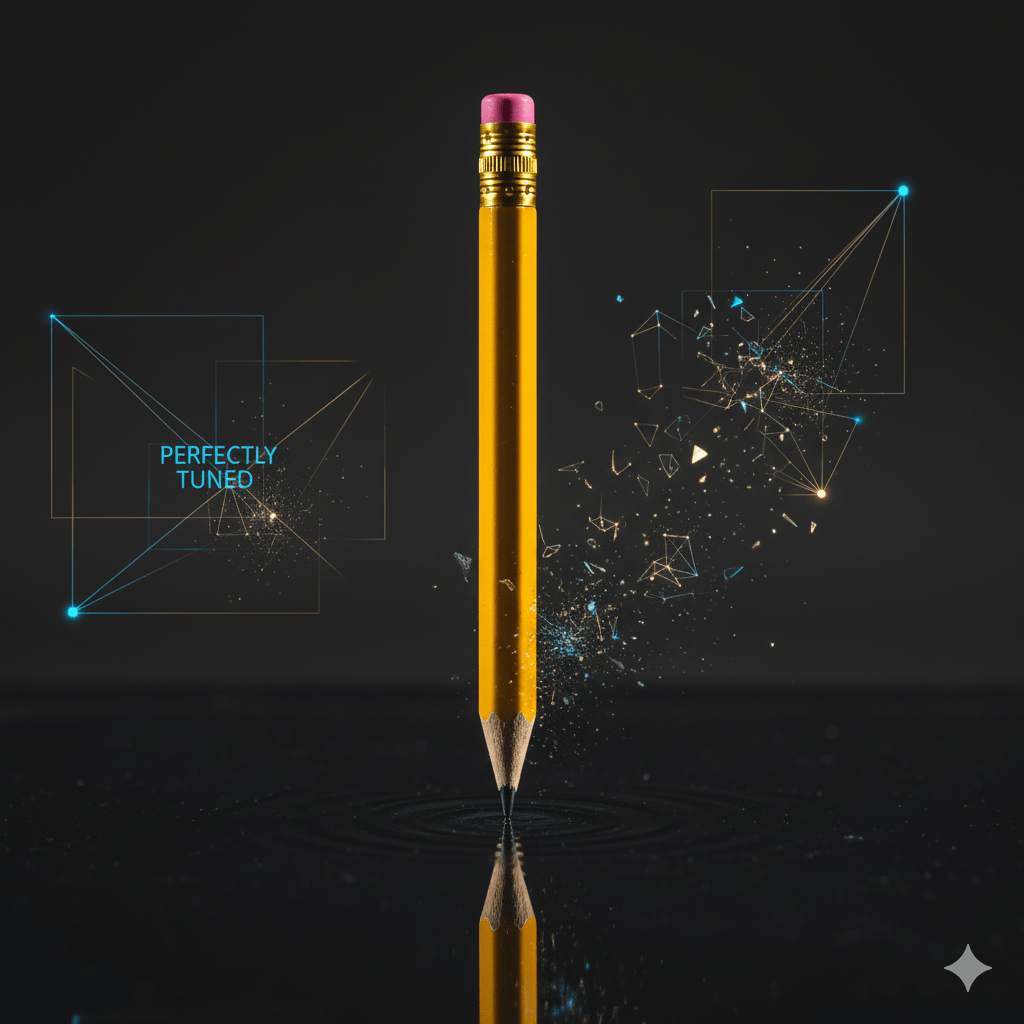

Meet The New Family of Blow-Ups Discovered By Google DeepMind

For centuries, mathematicians and physicists have used equations like the Euler and Navier-Stokes equations to describe how fluids move. A big mystery is whether these equations can predict that a smooth, well-behaved flow will suddenly develop a “singularity”—a point where things like velocity become infinite in a finite amount of time.

Most previous research has only found stable singularities—special solutions that still appear even if you slightly change the starting conditions. However, for the most important open problems (like the famous Millennium Prize Problem for Navier-Stokes), experts believe that if singularities exist, they must be unstable: they only happen if the initial conditions are tuned with extreme, almost impossible precision. These unstable singularities are extremely hard to find and study, especially with traditional mathematical or numerical methods.

Stable vs Unstable Singularities

Imagine you’re trying to balance a pencil perfectly upright on its tip.

- Stable singularity:

If the pencil is slightly tilted, it still stands up straight—small mistakes don’t matter much. This is like a stable singularity: it appears even if your starting point isn’t perfect. - Unstable singularity:

But in reality, if you try to balance a pencil on its tip, even the tiniest breeze or vibration will make it fall. You’d need impossibly precise conditions to keep it balanced. This is like an unstable singularity: it only happens if everything is tuned exactly right, and any tiny disturbance destroys it.

How can we systematically discover and precisely characterize these elusive, unstable singularities in fluid equations, and what can we learn from them?

The authors of this paper developed a new approach using physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) and high-precision optimization to search for self-similar singularities. They successfully discovered and validated multiple families of unstable singularities for several important fluid equations, providing the first systematic evidence of their existence. Their method not only finds these rare solutions but also measures their properties with enough accuracy to support rigorous mathematical proofs. This breakthrough opens new doors for tackling some of the deepest questions in mathematics and physics.

By combining modern machine learning with mathematical insight, the paper shows how to find and understand the most delicate and important types of singularities—those that only appear under perfect conditions—in the equations that govern fluid motion.

Discovering new solutions to century-old problems in fluid dynamics – Google DeepMind

Discovery of Unstable Singularities

Yongji Wang, Mehdi Bennani, James Martens, Sébastien Racanière, Sam Blackwell, Alex Matthews, Stanislav Nikolov, Gonzalo Cao-Labora, Daniel S. Park, Martin Arjovsky, Daniel Worrall, Chongli Qin, Ferran Alet, Borislav Kozlovskii, Nenad Tomašev, Alex Davies, Pushmeet Kohli, Tristan Buckmaster, Bogdan Georgiev, Javier Gómez-Serrano, Ray Jiang, Ching-Yao Lai

ai, AI in science, blow-ups, computational fluid dynamics, consciousness, Euler equations, fluid dynamics, fluid flow, fluid mechanics, god, Google DeepMind, machine learning, mathematical physics, Millennium Prize Problem, Navier-Stokes, philosophy, physics-informed neural networks, PINNs, science, scientific discovery, singularities, stable singularities, unstable singularities - Stable singularity:

-

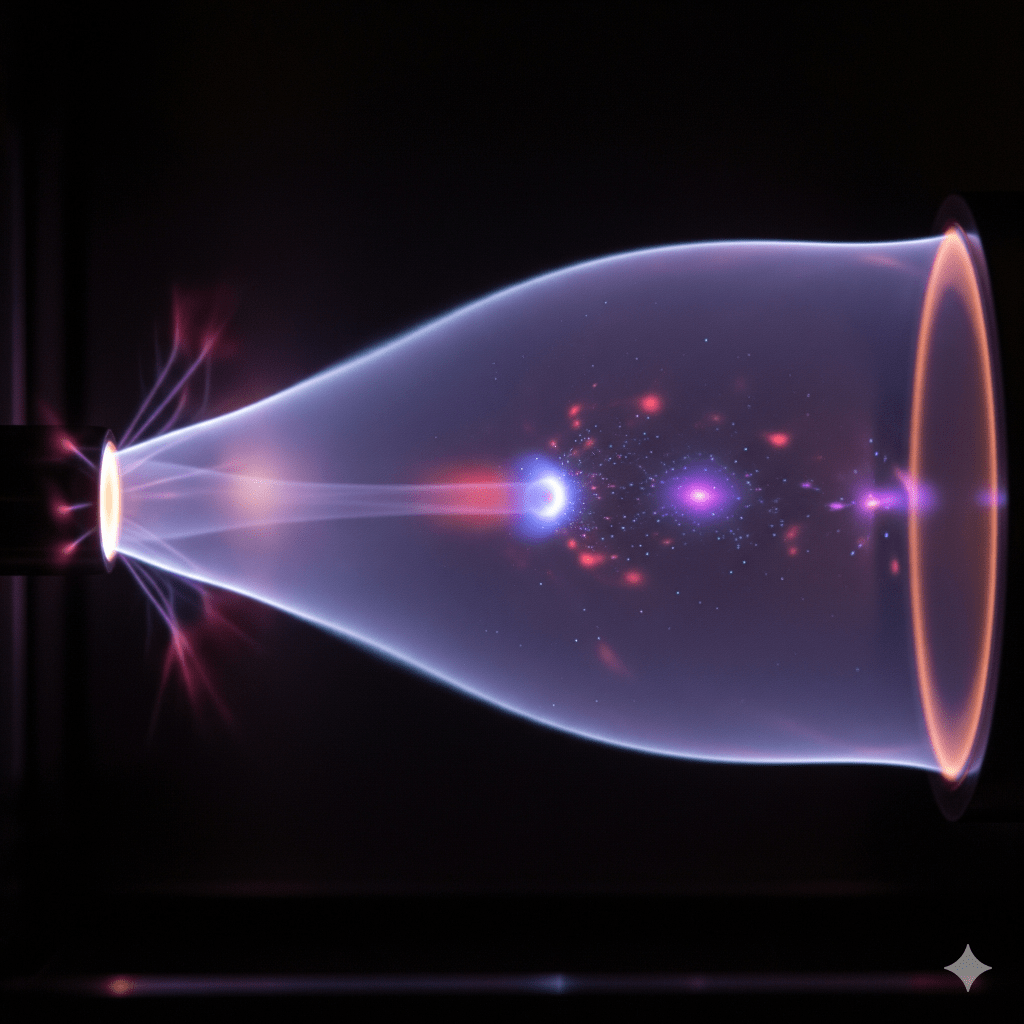

Plasma Jets in Vacuum – Literature Review

Executive Summary: A New Frontier in Engineering and Physics

Plasma, the “fourth state of matter,” has emerged from the confines of astrophysics and fusion research to become a transformative technology at the heart of modern industry and advanced science. When harnessed in a vacuum or low-pressure environment, its unique properties offer an unparalleled degree of control and precision, enabling breakthroughs that were once confined to the pages of science fiction. This literature review, “Plasma Jets in Vacuum: A Comprehensive Review of Generation, Characterization, and Applications,” synthesizes decades of research to provide a holistic understanding of this critical field.

Our review reveals a discipline at the intersection of fundamental physics and applied engineering. From the high-stakes world of deep-space propulsion to the meticulous requirements of semiconductor manufacturing and the delicate domain of biomedical engineering, vacuum-based plasma jets are the common denominator. In space, they power the most ambitious missions, with gridded ion thrusters delivering extraordinary fuel efficiency and Hall thrusters providing a balance of thrust and longevity. On Earth, their precision enables atomic-level control over materials, allowing for the creation of next-generation microelectronics and advanced surface coatings. A particularly promising frontier lies in biomedicine, where non-thermal (cold) plasma is revolutionizing sterilization techniques and accelerating wound healing without thermal damage.

Despite these remarkable advancements, the field is not without its challenges. The literature identifies significant knowledge gaps and unresolved debates, particularly in the development of predictive computational models. The complex, coupled feedback loops that govern plasma-induced erosion in Hall thrusters, for example, have thus far resisted complete theoretical description. Furthermore, a lack of standardized, comparative studies across different plasma jet devices and operating parameters complicates the generalization and reproducibility of research findings.

The path forward for plasma science lies in a profound synergy of advanced diagnostics and high-fidelity modeling. To bridge the gap between microscopic physical processes and macroscopic device performance, the field requires multi-channel diagnostic systems with higher spatiotemporal resolution and integrated, multi-scale computational models. By addressing these foundational challenges, researchers can move from a state of empirical optimization to one of predictive design, unlocking the full potential of this versatile and powerful technology.

Biomedical Applications, Hall thruster technology, Hall Thrusters, Ion Engines, Ion thruster propulsion, Literature Review, Low-Pressure Plasma, Materials Processing, Non-Thermal Plasma, Plasma Diagnostics, Plasma Jets, Plasma Jets in Vacuum, Plasma physics, Plasma Plume, Plasma Propulsion, Reactive Species, Sterilization, Vacuum Plasma, Vacuum Plasma Jets, Vacuum Technology