Circular Astronomy

Twitter List – See all the findings and discussions in one place

-

The Mysterious Discovery of JWST That No One Saw Coming

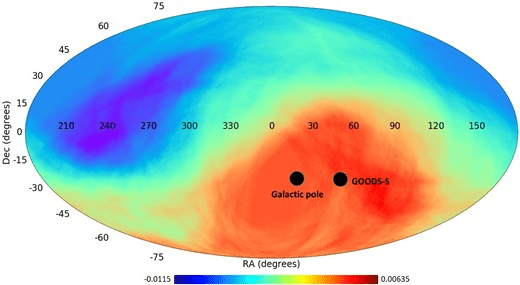

Are We Inside a Cosmic Whirlpool? Recent JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES) observations of mysterious cosmological anomalies in the rotational patterns of galaxies challenge our understanding of the universe and reveal surprising connections to natural growth patterns.

The rotation of 263 galaxies has been studied by Lior Shamir of Kansas State University, with 158 rotating clockwise and 105 rotating counterclockwise. The number of galaxies rotating in the opposite direction relative to the Milky Way is approximately 1.5 times higher than those rotating in the same direction.

New Cosmological anomalies that challenge our cosmological models and would have angered Einstein.

This observation challenges the expectation of a random distribution of galaxy rotation directions in the universe based on the isotropy assumption of the Cosmological Principle.

This is certainly not something Einstein would have liked to hear during his lifetime, but it would have excited Johannes Kepler.

What does this mean for our cosmological models, and why would it make Johannes Kepler happy?

The 1.5 ratio in galaxy rotation bias is intriguingly close to the Golden Ratio of 1.618. The Golden Ratio was one of Johannes Kepler’s two favorites. The astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) referred to the Golden Ratio as one of the “two great treasures of geometry” (the other being the Pythagorean theorem). He noted its connection to the Fibonacci sequence and its frequent appearance in nature.

What is the Fibonacci sequence?

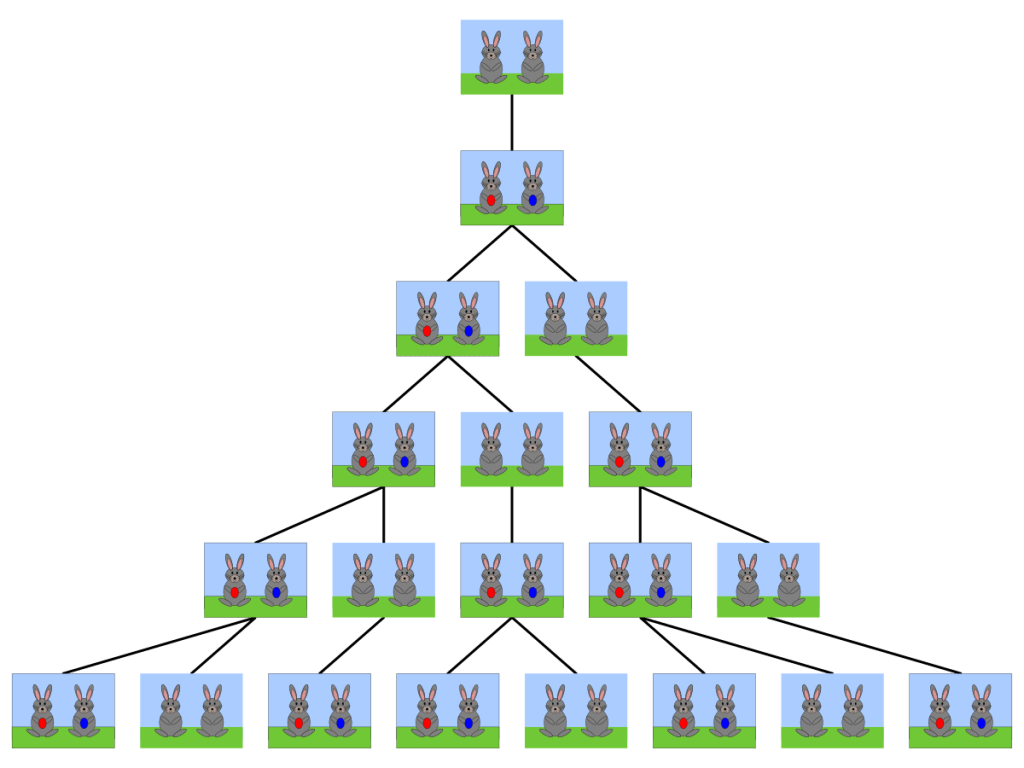

The Italian mathematician Leonardo of Pisa, better known as Fibonacci, introduced the world to a fascinating sequence in his 1202 book Liber Abaci (The Book of Calculation). This sequence, now famously known as the Fibonacci sequence, was presented through a hypothetical problem involving the growth of a rabbit population.

The growth of a rabbit population and why it matters?

Fibonacci posed the following question: Suppose a pair of rabbits can reproduce every month starting from their second month of life. If each pair produces one new pair every month, how many pairs of rabbits will there be after a year?

The solution unfolds as follows:

- In the first month, there is 1 pair of rabbits.

- In the second month, there is still 1 pair (not yet reproducing).

- In the third month, the original pair reproduces, resulting in 2 pairs.

- In the fourth month, the original pair reproduces again, and the first offspring matures and reproduces, resulting in 3 pairs.

Image Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FibonacciRabbit.svg

This pattern continues, with each new generation adding to the total, where each term is the sum of the two preceding terms.

The Fibonacci sequence generated is: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, …

While this idealized model of a rabbit population assumes perfect conditions—no sickness, death, or other factors limiting reproduction—it reveals a growth pattern that approaches the Golden Ratio as the sequence progresses. The ratio is determined by dividing the current population by the previous population. For example, if the current population is 55 and the previous population is 34, based on the Fibonacci sequence above, the ratio of 55/34 is approximately 1.618.

However, in reality, the growth rate of a rabbit population would likely fall below this mathematical ideal ratio due to natural constraints.Yet, this growth (evolutionary) pattern appears quite often in nature, such as in the growth patterns of succulents.

The growth patterns in succulents often follow the Fibonacci sequence, as seen in the arrangement of their leaves, which spiral around the stem in a way that maximizes sunlight exposure. This spiral phyllotaxis reflects Fibonacci numbers, where the number of spirals in each direction typically corresponds to consecutive terms in the sequence.

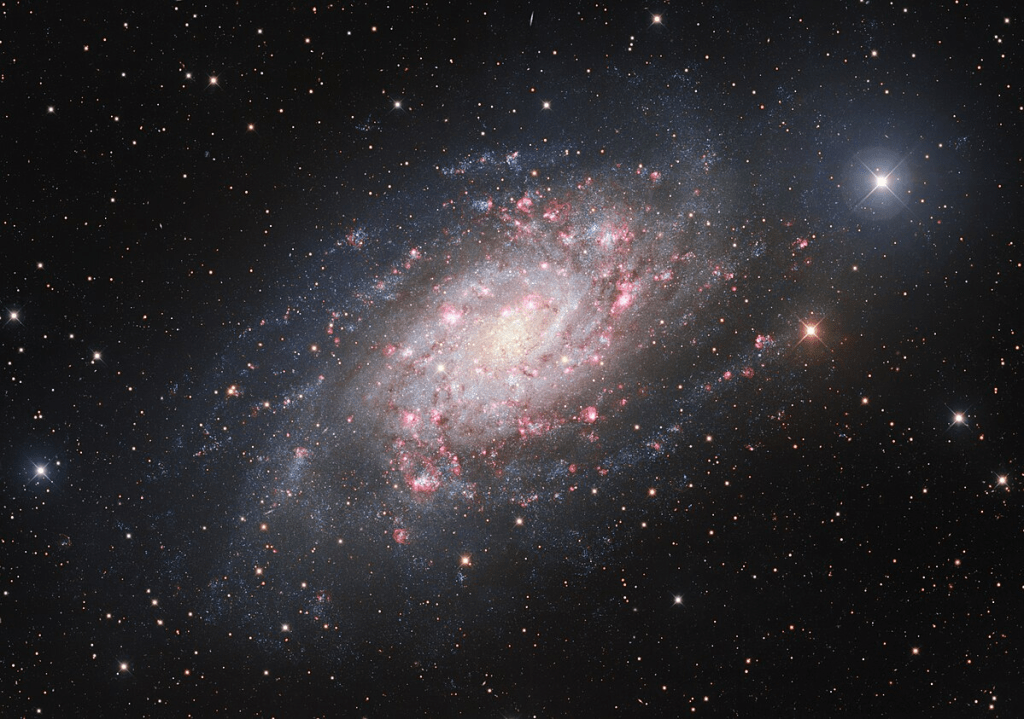

Spiral galaxies exhibit a similar growth (evolutionary) pattern in their spiral arms.

Spiral galaxies, like the Milky Way, display strikingly similar growth patterns in their spiral arms, where new stars are continuously formed and not in the center of the galaxy.

Image Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_Galaxy_of_Birth_and_Death.jpg

Returning to the observations and research conducted by Lior Shamir of Kansas State University using the JWST.

The most galaxies with clockwise rotation are the furthest away from us.

The GOODS-S field is at a part of the sky with a higher number of galaxies rotating clockwise

Image Source: Figure 10 https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staf292

“If that trend continues into the higher redshift ranges, it can also explain the higher asymmetry in the much higher redshift of the galaxies imaged by JWST. Previous observations using Earth-based telescopes e.g., Sloan Digital Sky Survey, Dark Energy Survey) and space-based telescopes (e.g., HST) also showed that the magnitude of the asymmetry increases as the redshift gets higher (Shamir 2020d).” Source: [1]“It becomes more significant at higher redshifts, suggesting a possible link to the structure of the early universe or the physics of galaxy rotation.” Source: [1]

Could the universe itself be following the same growth patterns we see in nature and spiral galaxies?

This new observation by Lior Shamir is particularly intriguing because, if we were to shift the perspective of our standard cosmological model—from one based on a singularity (the Big Bang ‘explosion’), which is currently facing a lot of challenges [2], to a growth (evolutionary) model—we would no longer be observing the early universe. Instead, we would be witnessing the formation of new galaxies in the far distance, presenting a perspective that is the complete opposite of our current worldview (paradigm).

NEW: Massive quiescent galaxy at zspec = 7.29 ± 0.01, just ∼700 Myr after the “big bang” found.

RUBIES-UDS-QG-z7 galaxy is near celestial equator.

It is considered to be a “massive quiescent galaxy’ (MQG).

These galaxies are typically characterized by the cessation of their star formation.

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/adab7a

The rotation, whether clockwise or counterclockwise, has not yet been observed.Reference

The distribution of galaxy rotation in JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey

Lior Shamir

[1 ] https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/538/1/76/8019798?login=false

The Hubble Tension in Our Own Backyard: DESI and the Nearness of the Coma Cluster

Daniel Scolnic, Adam G. Riess, Yukei S. Murakami, Erik R. Peterson, Dillon Brout, Maria Acevedo, Bastien Carreres, David O. Jones, Khaled Said, Cullan Howlett, and Gagandeep S. Anand

[2] https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2041-8213/ada0bd

Reading Recommendation:

The Golden Ratio, Mario Livio, 2002

Mario Livio was an astrophysicist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, which operates the Hubble Space Telescope.

RUBIES Reveals a Massive Quiescent Galaxy at z = 7.3

Andrea Weibel, Anna de Graaff, David J. Setton, Tim B. Miller, Pascal A. Oesch, Gabriel Brammer, Claudia D. P. Lagos, Katherine E. Whitaker, Christina C. Williams, Josephine F.W. Baggen, Rachel Bezanson, Leindert A. Boogaard, Nikko J. Cleri, Jenny E. Greene, Michaela Hirschmann, Raphael E. Hviding, Adarsh Kuruvanthodi, Ivo Labbé, Joel Leja, Michael V. Maseda, Jorryt Matthee, Ian McConachie, Rohan P. Naidu, Guido Roberts-Borsani, Daniel Schaerer, Katherine A. Suess, Francesco Valentino, Pieter van Dokkum, and Bingjie Wang (王冰洁)

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/adab7a

Appendix Spiral Galaxies:

Spiral galaxies are known for their stunning and symmetrical spiral arms, and many of them exhibit patterns that approximate logarithmic spirals, which are mathematically related to the Golden Ratio. While not all spiral galaxies perfectly follow the Golden Ratio, some exhibit spiral arm structures that closely resemble this pattern. Here are some notable examples of spiral galaxies with logarithmic spiral patterns:

1. Milky Way Galaxy

- Our own galaxy, the Milky Way, is a barred spiral galaxy with arms that approximate logarithmic spirals. The four primary spiral arms (Perseus, Sagittarius, Scutum-Centaurus, and Norma) follow a logarithmic pattern, though not perfectly aligned with the Golden Ratio.

2. M51 (Whirlpool Galaxy)

- The Whirlpool Galaxy is one of the most famous examples of a spiral galaxy with well-defined logarithmic spiral arms. Its arms are nearly symmetrical and exhibit a pattern that closely resembles the Golden Ratio.

3. M101 (Pinwheel Galaxy)

- The Pinwheel Galaxy is a grand-design spiral galaxy with prominent and well-defined spiral arms. Its structure is often cited as an example of a logarithmic spiral in astronomy.

4. NGC 1300

- NGC 1300 is a barred spiral galaxy with a striking logarithmic spiral pattern in its arms. It is often studied for its near-perfect spiral structure.

5. M74 (Phantom Galaxy)

- The Phantom Galaxy is another grand-design spiral galaxy with arms that follow a logarithmic spiral pattern. Its symmetry and structure make it a textbook example of this phenomenon.

6. NGC 1365

- Known as the Great Barred Spiral Galaxy, NGC 1365 has a prominent bar structure and spiral arms that exhibit a logarithmic pattern.

7. M81 (Bode’s Galaxy)

- Bode’s Galaxy is a spiral galaxy with arms that follow a logarithmic spiral structure. It is one of the brightest galaxies visible from Earth and a popular target for astronomers.

8. NGC 2997

- This galaxy is a grand-design spiral galaxy with arms that closely resemble logarithmic spirals. It is located in the constellation Antlia.

9. NGC 4622

- Known as the “Backward Galaxy,” NGC 4622 has a unique spiral structure with arms that follow a logarithmic pattern, though its rotation direction is unusual.

10. M33 (Triangulum Galaxy)

- The Triangulum Galaxy is a smaller spiral galaxy with arms that exhibit a logarithmic spiral structure. It is part of the Local Group, along with the Milky Way and Andromeda.

-

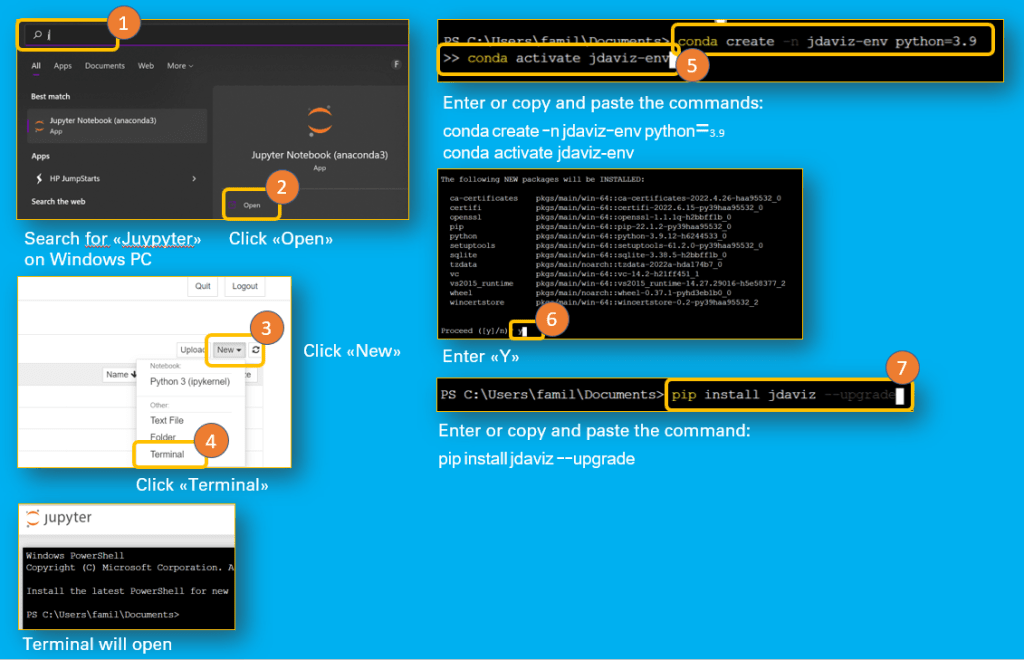

How to Download, View, And Edit Images from the James Webb Space Telescope with Jdaviz and Imviz

Like to comfortably view and edit images from the Jamew Webb Space Telescope like an astronomer ?

Then follow this step by step cheatsheet guides if you are using windows on a PC .

Main Software Components

There are three key software components required:

- Microsoft C++ 14

- Jupyter Notebook (Python)

- Jdaviz

Additonal

- MAST Token to be able to download the images with Imviz.

Prerequsites:

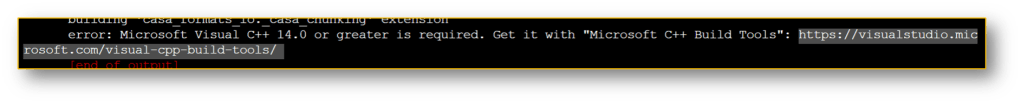

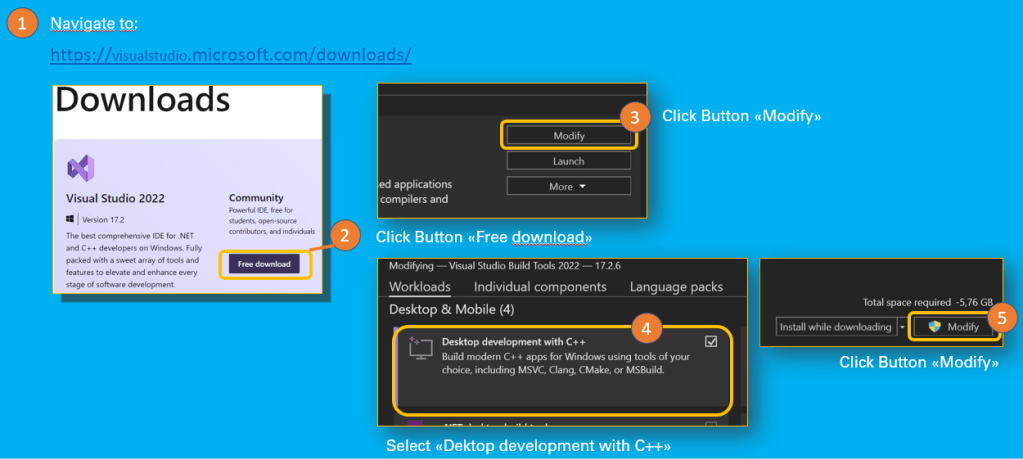

Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater

error: Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater is required If Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater is not installed, the installation of Jdaviz will fail. Without Jdaviz the downloaded images from the James Webb Space Telescope cannot be edited.

How to install Microsoft Visual C++

- Navigate to: https://visualstudio.microsoft.com/downloads/

- Download Visual Studio 2022 Community version

- Follow the instructions in this post: Install C and C++ support in Visual Studio | Microsoft Docs

Cheatsheet: Install Visual Studio 2022 MAST Token

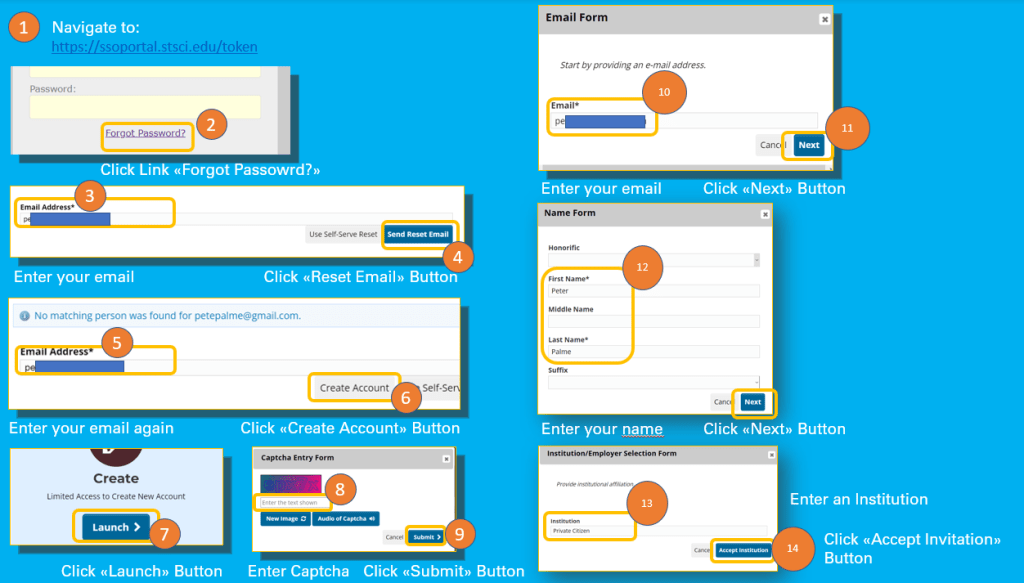

- Navigate to https://ssoportal.stsci.edu/token

If you do not have not an account yet, please follow below steps to create your account:

- Click on the Forgotten Password? link

- Enter your email Adress

- Click Send Reset Email Button

- Click Create Account Button

- Click Launch Button

- Enter the Captcha

- Click Submit Button

- Enter your email

- Click Next Button

- Fill in the Name Form

- Click Next Button

- Fill in the Insitution (e.g. Private Citizen or Citizen Scientist)

- Click Accept Institution Button

- Enter Job Title (whatever you are or like to be ;-))

- Click Next Button

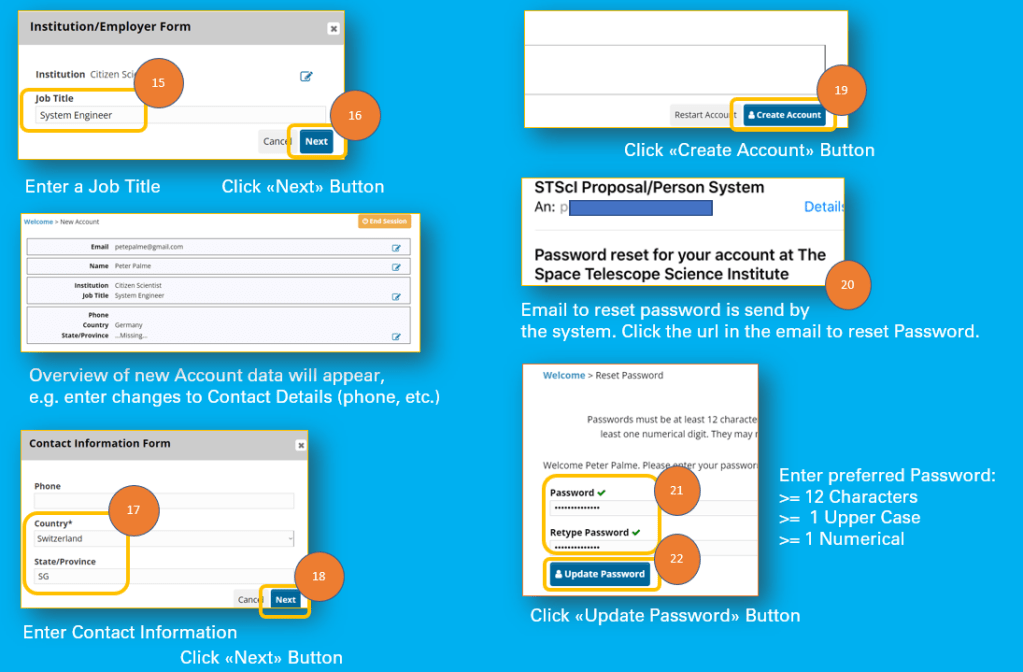

- New Account Data for your review is presented, in case of missing contact data, step 17 might be necessary

- Fill in Contact Information Form

- Click Next Button

- Click Create Account Button

- In your email account open the reset password emal

- Click on the link

- Enter Password

- Enter Retype Password

- Click Update Password

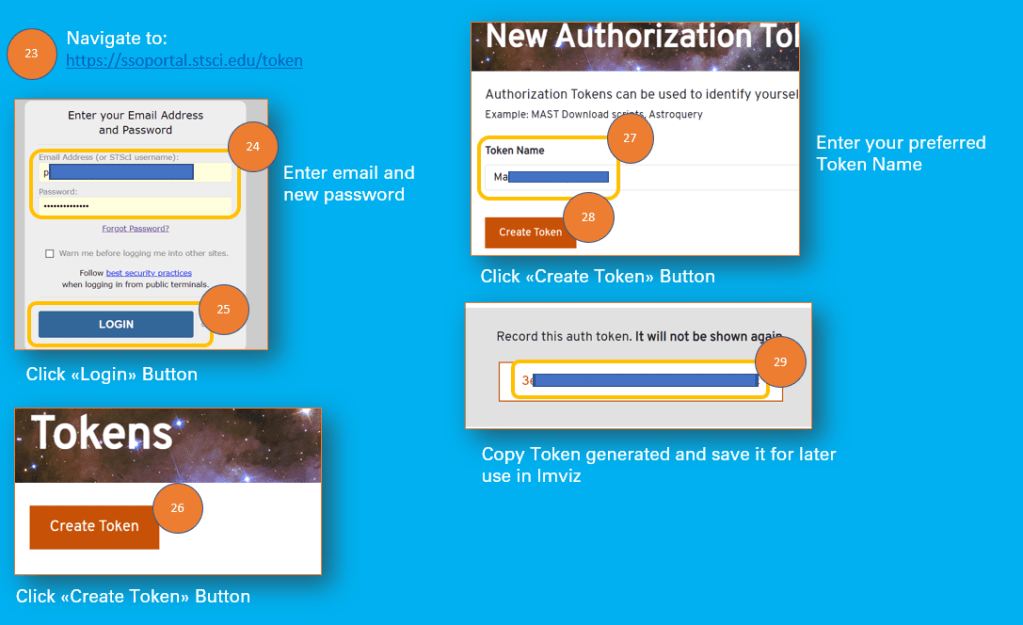

- Navigate to https://ssoportal.stsci.edu/token

- Now log on with your email and new account password

- Click Create Token Button

- Fill in a Token Name of your choice

- Click Create Token Button

- Copy the Token Number and save it for later use in Imviz to download the images from the James Webb Space Telescope

Quite a lot of steps for a Token.

Cheatsheet: Create MAST Account

Cheatsheet: Set Passord for new Account

Cheatsheet: Create MAST Token for use in Imviz Jupyter Notebook

Jupyter notebook comes with the ananconda distribution.

- Navigate to: https://www.anaconda.com/products/distribution#windows

- Follow the instructions at: https://docs.anaconda.com/anaconda/install/windows/

Install Jdaviz

- Navigate to: Installation — jdaviz v2.7.2.dev6+gd24f8239

- Open the Jupyter Notebook

- Open Terminal from Jupyter Notebook

- Follow the instruction in: Installation — jdaviz v2.7.2.dev6+gd24f8239

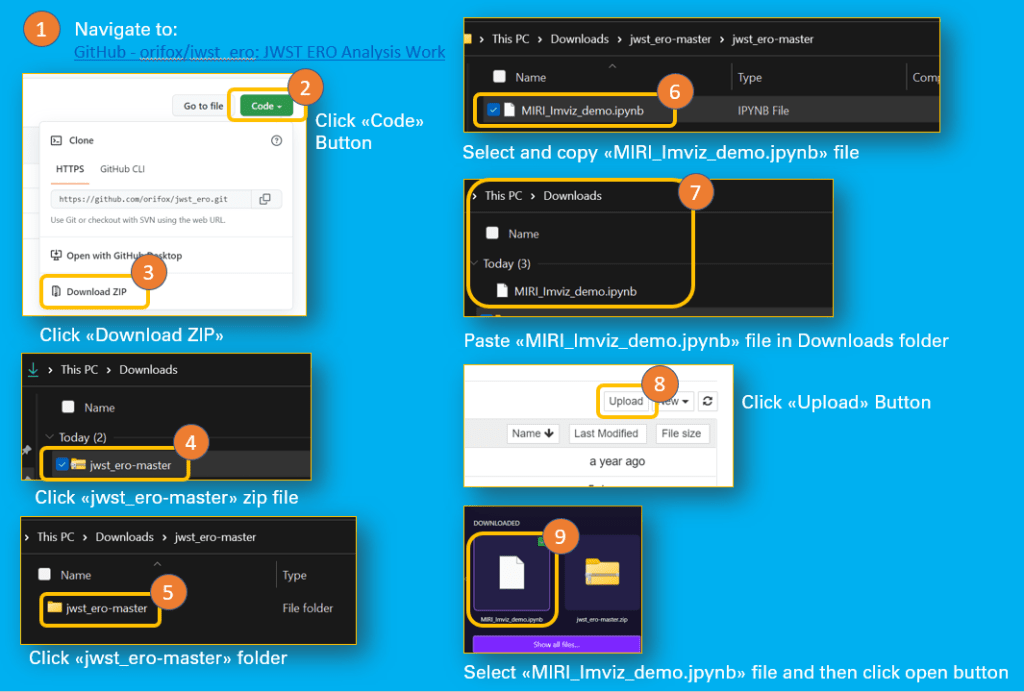

Cheatsheet: Install Jdaviz How to use IMVIZ

Imviz is installed together with Jdaviz.

Following steps to take in order to use Imviz:

- Navigate to: GitHub – orifox/jwst_ero: JWST ERO Analysis Work

- Click Code Button

- Click Download Zip

- If you do not have unzip, then the next steps might work for you:

- In Download Folder (PC) click the jwst_ero master zip file

- Then click on the folder jwst_ero master

- Copy file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb

- Paste the file in the download folder

- Open Jupyter notebook

- Click Upload Button

- Select the file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb

- Click Open Button

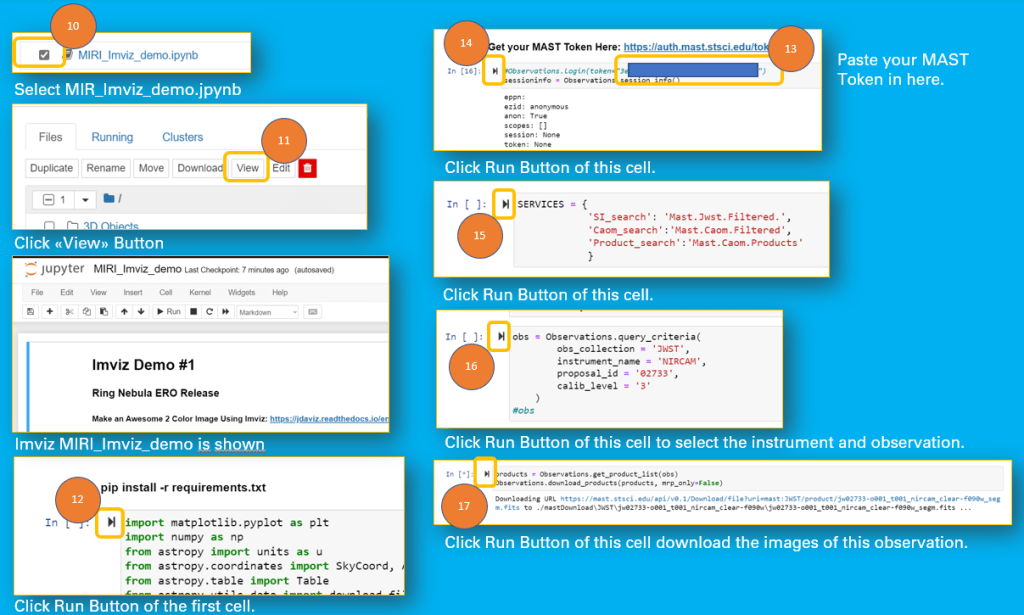

- Select the file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb in the Jupyter Notebook file list

- Click View Button

- Click Run Button First Cell

- Paste MAST Token in next cell

- Click Run Button of this Cell

- Click then Run Button of next Cell

- Click Run Button of the following Cell

- Click Run Button of the next Cell to download the images

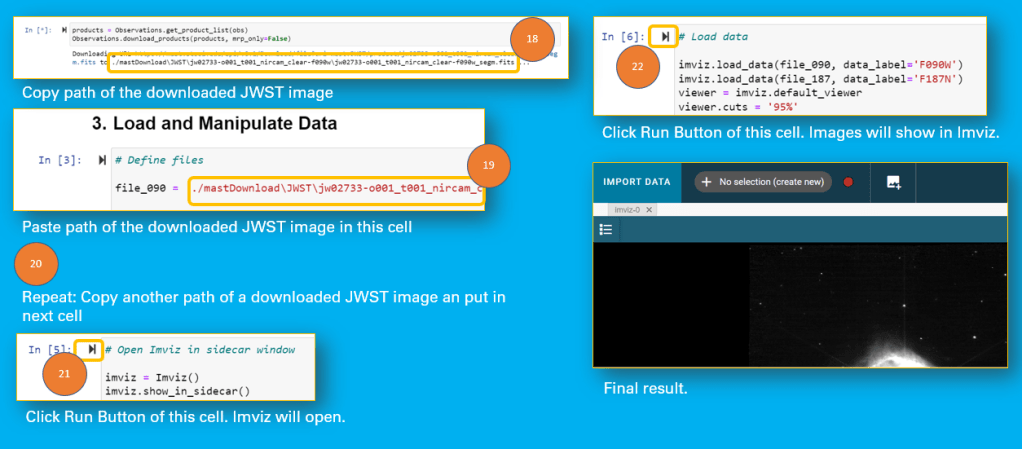

- Copy the link to the downloaded image file

- Past link into the First Cell in 3. Load and Manipulate Data

- Do the same in the next Cell

- Click Run Button of the Cell to open Imviz

- Click Run Button on the next Cell to load images in Imviz

Cheatsheet: Upload MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb in Jupyter notebook Now all set to download the images of the JWST observation:

Cheatsheet: Download JWST images with Imviz And now all is set to open and edit the images in Imviz

Cheatsheet: Open Images in Imviz And finally you are ready to follow the video tutorials in order to learn how to use Imviz to manipulate the JWST images.

Video Tutorials for Imviz:

And this is the master Ori Fox of the Imviz demo notebook file if you like to follow him on Twitter

-

Time for a new scientific debate – Accretion vs Convection

To what degree is gravity needed to form structures in space? While many believe that celestial bodies (stars, planets, moons, meteoroids) can only form through gravitational attraction in the vacuum of space, I believe that these bodies form through a thermodynamic process similar to the formation of hydrometeors (e.g., hail). This is because our solar system possesses a boundary layer, a discovery made by the Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) mission in 2013.

In simple terms: Planets, moons, and small bodies are formed within convection cells created by the jet streams of a young sun, under the influence of strong magnetic fields.

Recently, a new paper introduced quantum models in which gravity emerges from the behavior of qubits or oscillators interacting with a heat bath.

More details and link to the research paper: On the Quantum Mechanics of Entropic Forces

https://circularastronomy.com/2025/10/09/entropic-gravity-explained-how-quantum-thermodynamics-could-replace-gravitons/ -

Solving the Clay Millennium Problem 3D incompressible Navier–Stokes equations

Solving the Millennium Problem with AI is not new. Javier Gómez Serrano (Mathematician, Brown University) teamed up with the Google DeepMind team.

Below, I propose a conceptual whitepaper—created with OpenAI ChatGPT—to address one of the Millennium Prize Problems.

Introduction

The Clay Millennium Problem on the 3D incompressible Navier–Stokes equations asks whether smooth solutions with smooth initial data remain smooth for all time, or if finite-time singularities (blow-up) can occur. Despite major progress (local well-posedness, global regularity in 2D, partial regularity results, small-data theorems in critical spaces), the 3D case with large data remains open.

This note outlines a conceptual research program that integrates overlooked structural elements of the equations:

• Geometric depletion of vortex stretching (inspired by Viktor Schauberger’s natural vortex observations),

• Sparsity of intermittent singular sets (Caffarelli–Kohn–Nirenberg), and

• Pressure as a global stabilizer.The central idea is to convert vortex geometry into a quantitative damping factor in scale-critical estimates, closing the gap in the current proof strategy.

Additionally, in the future, the condition of the boundary layer that defines a liquid will be explored. This is not yet part of the conceptual whitepaper.

Executive Summary by Storm Gini Stanford AI Tool: 3D Navier Stokes Millenium Problem

Navier–Stokes Framework

We consider the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations on \mathbb{R}^3:

\begin{cases} \partial_t u + (u\cdot\nabla)u = -\nabla p + \nu \Delta u + f, \ \nabla \cdot u = 0, \quad u(x,0) = u_0(x), \end{cases}

with smooth divergence-free u_0 and smooth forcing f.

The unknowns are the velocity field u(x,t) \in \mathbb{R}^3 and pressure field p(x,t) \in \mathbb{R}.

Overlooked Structural Elements

3.1 Vorticity Alignment

Define the vorticity \omega = \nabla \times u. The vortex stretching term is

(\omega \cdot \nabla)u = S\omega, \quad S = \tfrac12(\nabla u + \nabla u^\top).

If \omega aligns with the eigenvector of S corresponding to its maximal eigenvalue, stretching is maximal. Otherwise, the stretching weakens.We define the alignment deficit:

\mathcal{A}(x,t) := 1 – (\xi(x,t)\cdot e_{\max}(x,t))^2,

where \xi = \omega/|\omega|. Numerics suggest \mathcal{A} is often nontrivial in real flows, but it has not been fully exploited analytically.3.2 Sparsity of Singular Sets

Caffarelli–Kohn–Nirenberg (1982) proved that possible singularities occupy a set of parabolic Hausdorff dimension ≤ 1. This indicates that regions of extreme steepness are sparse, yet most analyses ignore this sparseness when estimating nonlinear terms.

3.3 Pressure Stabilization

The pressure satisfies the Poisson equation:

\Delta p = -\nabla \cdot \nabla \cdot (u\otimes u).

Traditionally pressure is projected away (Helmholtz–Leray). But as a nonlocal constraint, pressure redistributes stresses and can dampen coherent growth of steepness, especially on sparse sets.Proposed Lemmas

Lemma 1 (Geometric ε-Regularity, local)

There exists \varepsilon > 0 such that if for a parabolic cylinder Q_r(x_0,t_0):

[

\Big(\fint_{Q_r} |u|^3 + |p|^{3/2}\Big) \cdot \Big(\fint_{Q_r} \mathcal{A}\Big) < \varepsilon,

]

then u is smooth at (x_0,t_0).This strengthens classical ε-regularity by factoring in alignment.

Lemma 2 (Dyadic Flux Inequality with Alignment)

For dyadic block u_j at frequency scale 2^j:

\frac{d}{dt}|u_j|_2^2 \;\le\; -c\nu 2^{2j}|u_j|_2^2 + C(1-\cos^2\theta_j)\,\Phi_j(u),

where \theta_j is the average vorticity–strain angle at scale 2^j, and \Phi_j(u) the nonlinear flux.This shows that alignment deficit directly damps the critical energy cascade.

Lemma 3 (Pressure–Sparsity Bound)

On a parabolic cylinder Q_r where the set {|\nabla u| > \Lambda} is \alpha-sparse:

[

\fint_{Q_r} \lambda_{\max}(\nabla^2 p)\, \chi_{{|\nabla u|>\Lambda}} \le C(\alpha)\,\fint_{Q_r} |u|^2/r^2.

]

This prevents pressure Hessian from reinforcing stretching in sparse regions.Rigidity Argument

Assume blow-up occurs. Rescaling yields a nontrivial ancient mild solution bounded in a critical norm (e.g. L^\infty_t L^3_x or BMO^{-1}).

• Lemma 1 ensures local smoothness wherever alignment deficit persists.

• Lemma 2 ensures top-scale damping of energy flux.

• Lemma 3 ensures pressure cannot sustain coherent stretching on sparse singular sets.Together, these imply the ancient solution must vanish — a rigidity contradiction, excluding finite-time blow-up.

Interpretation: Schauberger’s “Implosion vs Explosion”

Schauberger described vortices as stabilizers (implosion) vs destabilizers (explosion). In Navier–Stokes terms:

• Implosion = alignment deficit > 0 ⇒ stretching depleted ⇒ smoothness preserved.

• Explosion = perfect alignment ⇒ dangerous stretching ⇒ potential blow-up.Thus his intuition aligns with the analytic mechanism we propose.

Conclusion & Outlook

This program integrates geometric depletion, sparsity, and pressure redistribution into a single framework. Proving Lemmas 1–3 would yield the missing scale-critical estimate and close the Navier–Stokes global regularity problem.

Next steps:

- Prove Lemma 1 rigorously by modifying CKN ε-regularity.

- Establish Lemma 2 via dyadic paraproduct estimates.

- Develop Lemma 3 with Calderón–Zygmund theory and sparsity.

- Attempt rigidity proof for ancient solutions.

References

• Caffarelli, Kohn, Nirenberg (1982) — partial regularity.

• Escauriaza, Seregin, Šverák (2003) — L^3-regularity criterion.

• Constantin, Fefferman, Majda (1996) — geometric depletion.

• Koch, Tataru (2001) — critical BMO^{-1} well-posedness.

• Viktor Schauberger (1940s–50s) — vortex observations, implosion vs explosion.Literature Review with Gemini Advance based on this Research Note

Using State of the Art Problem Solving for the Navier-Stokes Equations

-

The Fastest Way to Understand Any Mathematical Function

Decode any math function in minutes: A Step-by-Step Framework powered by AI

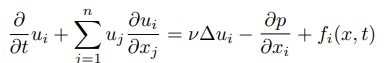

Example Navier-Stokes equation:

Show an example of the output or outcome of this function?

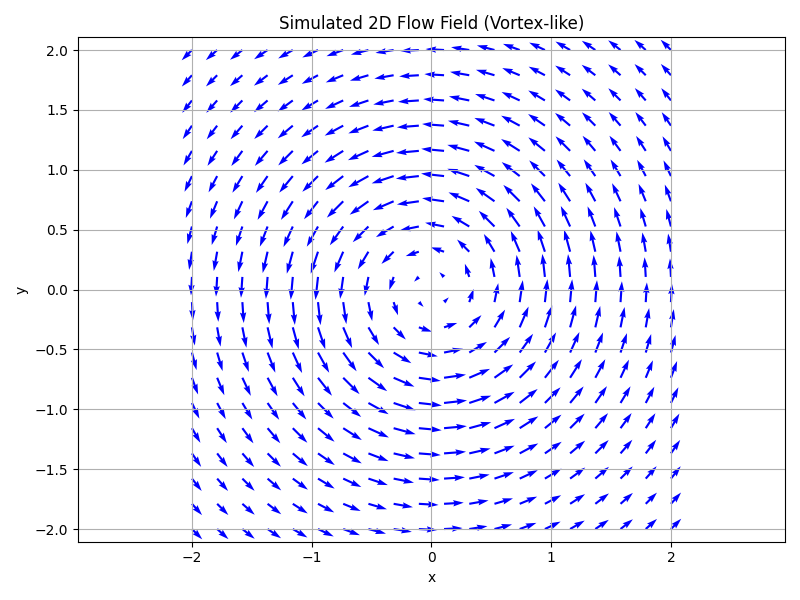

Example: 2D Vortex Flow

Let’s consider a simple 2D example: a decaying vortex in a viscous fluid. This is a classic solution to the Navier-Stokes equations in two dimensions.

Setup:

- No external force: ( f_i(x, t) = 0 )

- Initial velocity field: circular vortex

- Viscosity ( \nu > 0 )

Outcome:

Over time, the vortex slows down and diffuses due to viscosity. The velocity field becomes smoother, and the rotational motion weakens.

What exactly is this function trying to teach? What problem does this help me solve?

What is it trying to teach?

It models how fluids (like air, water, oil, etc.) move and behave under various conditions. Specifically, it teaches:

- Momentum conservation in a fluid.

- How velocity, pressure, viscosity, and external forces interact.

- The balance between inertia, pressure gradients, viscous diffusion, and external forces.

What problems does it help solve?

The Navier-Stokes equations are used to solve real-world problems involving fluid flow. Here are some examples:

1. Engineering & Design

- Aerodynamics: Designing cars, airplanes, and drones for optimal airflow.

- Hydraulics: Modeling water flow in pipes, dams, and irrigation systems.

2. Weather & Climate

- Predicting weather patterns, storms, and climate dynamics.

3. Medicine & Biology

- Simulating blood flow in arteries or airflow in lungs.

4. Environmental Science

- Modeling pollution dispersion in air or water.

- Understanding ocean currents and atmospheric circulation.

5. Computer Graphics & Animation

- Creating realistic fluid simulations in movies and video games.

Why is it challenging?

Despite its importance, solving the Navier-Stokes equations analytically is extremely difficult in most cases. That’s why we often use numerical simulations (like Computational Fluid Dynamics, CFD) to approximate solutions.

Instead of using mathematical symbols, express the function entirely in words.

The rate of change of the fluid’s velocity in a given direction, plus the combined effect of all the fluid’s velocity components interacting with each other across space, is equal to the influence of viscosity spreading the velocity out, minus the change in pressure in that direction, plus any external force acting on the fluid at that location and time.

Breaking it down further:

- Rate of change of velocity: How fast the fluid’s speed is changing over time in a specific direction.

- Advection (nonlinear interaction): How the fluid’s own movement affects its velocity—like how a current carries itself forward.

- Viscous diffusion: The smoothing effect of internal friction (viscosity), which spreads out sharp changes in velocity.

- Pressure gradient: How differences in pressure push the fluid from high-pressure areas to low-pressure areas.

- External forces: Any outside influence like gravity, magnetic fields, or applied forces that affect the fluid’s motion.

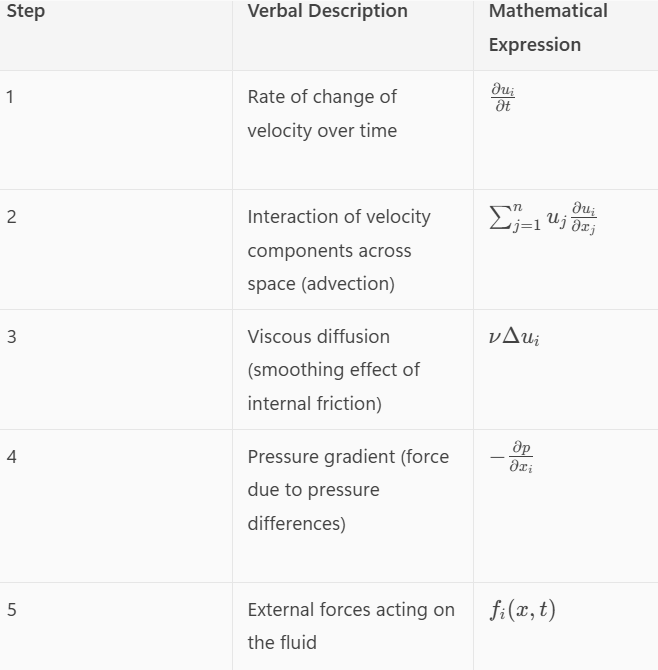

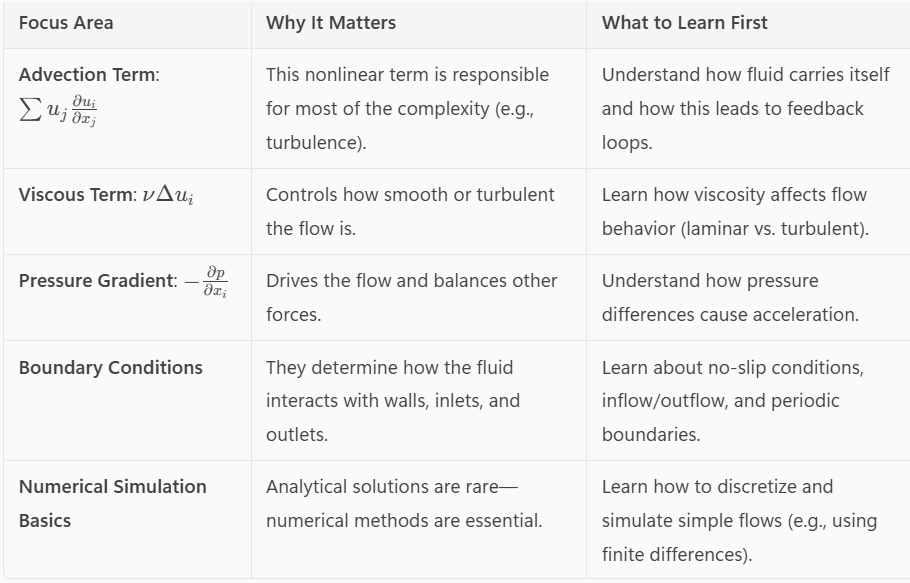

Now, list the descriptions in words (steps 1 to 5) in a table, and show how each one relates to the corresponding mathematical expression in the function.

Step Verbal Description Mathematical Expression Meaning 1 Rate of change of velocity over time \frac{\partial u_i}{\partial t} How fast the fluid’s velocity is changing at a point in time. 2 Interaction of velocity components across space (advection) \sum_{j=1}^n u_j \frac{\partial u_i}{\partial x_j} How the fluid’s own motion carries and changes its velocity. 3 Viscous diffusion (smoothing effect of internal friction) \nu \Delta u_i How viscosity spreads out sharp changes in velocity. 4 Pressure gradient (force due to pressure differences) -\frac{\partial p}{\partial x_i} How pressure differences push the fluid in a certain direction. 5 External forces acting on the fluid f_i(x, t) Any outside influence like gravity, magnetic fields, or applied forces.

Which parts are worth focusing on first (80/20)?

Apply all these frameworks to above mathematical function

1. Structural Analysis Domain & Codomain:

What inputs are allowed?

What outputs are possible?

Continuity & Differentiability: Is the function smooth?

Are there jumps or corners?

Symmetry: Even, odd, periodic?

Monotonicity: Increasing, decreasing, or constant?

2. Graphical Interpretation Plot the function:

Visualizing the function often reveals behavior (e.g., asymptotes, extrema, inflection points). L

evel sets / Contour plots (for multivariable functions): Show where the function takes constant values.

3. Algebraic Tools Taylor Series / Approximations:

Understand local behavior near a point.

Factorization / Simplification: Reduce complexity to reveal structure.

Limits and asymptotics: Understand behavior at boundaries or infinity.

4. Functional Perspective Linear vs. Nonlinear:

Linear functions are easier to analyze and often serve as approximations. Convexity: Important in optimization—convex functions have global minima. Operator View: In functional analysis, functions can be seen as operators acting on spaces.

5. Computational Tools Symbolic computation (e.g., WolframAlpha, SymPy): For derivatives, integrals, simplifications.

Numerical evaluation: Plug in values to get a feel for the function.

Automatic plotting: Tools like Desmos, GeoGebra, or Python (Matplotlib, Plotly).

6. Contextual Frameworks Optimization:

Is the function a cost, utility, or energy function?

Control theory: Is it part of a system dynamic?

Physics / Engineering: Does it model a real-world phenomenon?

7. Heuristic Questions Ask yourself:

What happens as x→∞ x→∞ or x→0 x→0?

Where is the function zero?

Where is it undefined?

What are the critical points?🔍 1. Structural Analysis

Aspect Explanation Domain Space (x, y, z) and time (t) Codomain Vector field (velocity components in 3D) Continuity Assumes smooth, differentiable velocity and pressure fields Symmetry No inherent symmetry unless imposed by boundary conditions Monotonicity Not monotonic; fluid behavior is dynamic and can oscillate or reverse direction 📈 2. Graphical Interpretation

- Plotting: Direct visualization is complex due to the vector and PDE nature, but simulations show vortices, turbulence, and laminar flow.

- Level Sets / Contours: Often used to visualize pressure or velocity magnitude in 2D slices of the domain.

🧮 3. Algebraic Tools

Tool Insight Taylor Series Used to linearize the equation near steady states (e.g., for stability analysis) Simplification In low Reynolds number (viscous-dominated), convective terms can be neglected Limits & Asymptotics At high Reynolds numbers, turbulence and chaotic behavior emerge 🧠 4. Functional Perspective

Aspect Classification Linearity Nonlinear, due to the convective term ( (u \cdot \nabla)u ) Convexity Not convex; multiple solutions and instabilities are possible Operator View A differential operator acting on velocity and pressure fields 🧰 5. Computational Tools

- Symbolic Tools: Used to derive and manipulate the equations (e.g., SymPy, Mathematica)

- Numerical Solvers: Finite element, finite volume, and spectral methods (e.g., OpenFOAM, ANSYS Fluent)

- Visualization: Matplotlib, ParaView, or CFD software for flow field visualization

🧭 6. Contextual Frameworks

Field Application Optimization Used in flow control problems (e.g., minimizing drag) Control Theory Applied in feedback control of fluid systems (e.g., HVAC, drones) Physics/Engineering Core to fluid dynamics, aerodynamics, weather modeling, and biomedical flows 🧠 7. Heuristic Questions

Question Answer What happens as ( x \to \infty )? Depends on boundary conditions; often assumed to decay to zero Where is the function zero? When velocity and external forces are zero Where is it undefined? Singularities may occur in turbulent or chaotic flows What are the critical points? Where velocity gradients vanish or change sign (e.g., stagnation points) Who gave the best-ever explanation of this function so that even people with no mathematical background could understand it, and how did they explain it?

🧠 Who explained it best?

Dr. Steven Strogatz

- Professor at Cornell University

- Contributor to The New York Times and author of popular science books like The Joy of x

📖 How did he explain it?

In his writing and talks, Strogatz breaks down the Navier-Stokes equations using everyday analogies and plain language. Here’s a simplified version of his approach:

🌀 1. Think of Fluid as a Crowd of Tiny Particles

He invites readers to imagine a fluid as a swarm of tiny particles—like a crowd of people moving through a city.

🧭 2. What Influences Their Motion?

Each particle’s motion is influenced by:

- Inertia: It wants to keep moving in the same direction.

- Pressure: Like people moving away from a crowded area.

- Viscosity: Like friction between people slowing each other down.

- External forces: Like wind or gravity pushing the crowd.

🧮 3. The Equation is a Balance Sheet

He describes the Navier-Stokes equation as a balance sheet:

- On the left: how the velocity of the fluid is changing.

- On the right: all the reasons why it’s changing (pressure, viscosity, forces).

🎨 4. He Uses Visual Metaphors

Instead of diving into symbols, he uses visual metaphors:

- Flowing honey vs. rushing water

- Smoke swirling in air

- Traffic jams as analogies for pressure buildup

🧩 Why it works so well:

- No equations at first—just intuition.

- Relatable metaphors—like crowds, traffic, and weather.

- Builds curiosity—then introduces the math once the concept is clear.

Frameworks for Understanding Mathematical Functions

🔍 1. Structural Analysis

- Domain & Codomain: What inputs are allowed? What outputs are possible?

- Continuity & Differentiability: Is the function smooth? Are there jumps or corners?

- Symmetry: Even, odd, periodic?

- Monotonicity: Increasing, decreasing, or constant?

📈 2. Graphical Interpretation

- Plot the function: Visualizing the function often reveals behavior (e.g., asymptotes, extrema, inflection points).

- Level sets / Contour plots (for multivariable functions): Show where the function takes constant values.

🧮 3. Algebraic Tools

- Taylor Series / Approximations: Understand local behavior near a point.

- Factorization / Simplification: Reduce complexity to reveal structure.

- Limits and asymptotics: Understand behavior at boundaries or infinity.

🧠 4. Functional Perspective

- Linear vs. Nonlinear: Linear functions are easier to analyze and often serve as approximations.

- Convexity: Important in optimization—convex functions have global minima.

- Operator View: In functional analysis, functions can be seen as operators acting on spaces.

🧰 5. Computational Tools

- Symbolic computation (e.g., WolframAlpha, SymPy): For derivatives, integrals, simplifications.

- Numerical evaluation: Plug in values to get a feel for the function.

- Automatic plotting: Tools like Desmos, GeoGebra, or Python (Matplotlib, Plotly).

🧭 6. Contextual Frameworks

- Optimization: Is the function a cost, utility, or energy function?

- Control theory: Is it part of a system dynamic?

- Physics / Engineering: Does it model a real-world phenomenon?

🧑🏫 7. Heuristic Questions

Ask yourself:

- What happens as ( x \to \infty ) or ( x \to 0 )?

- Where is the function zero?

- Where is it undefined?

- What are the critical points?

-

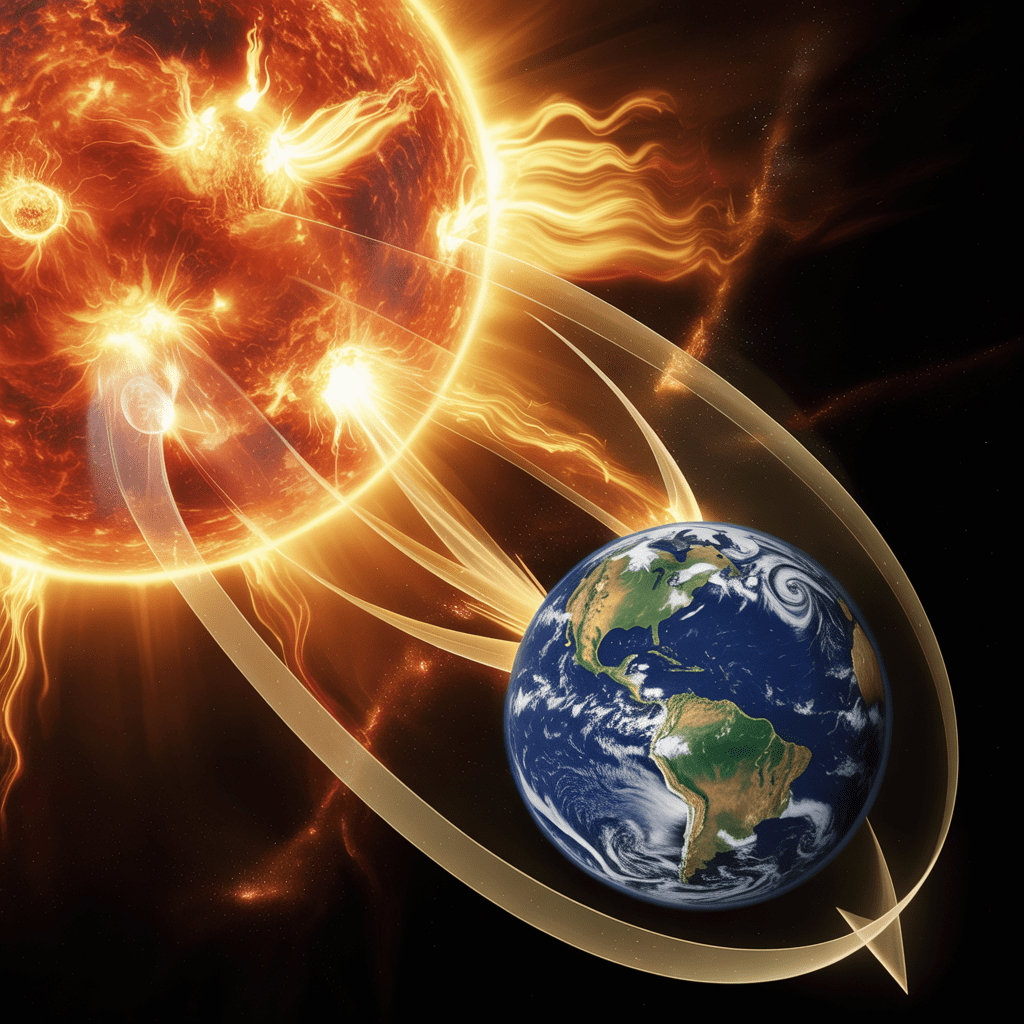

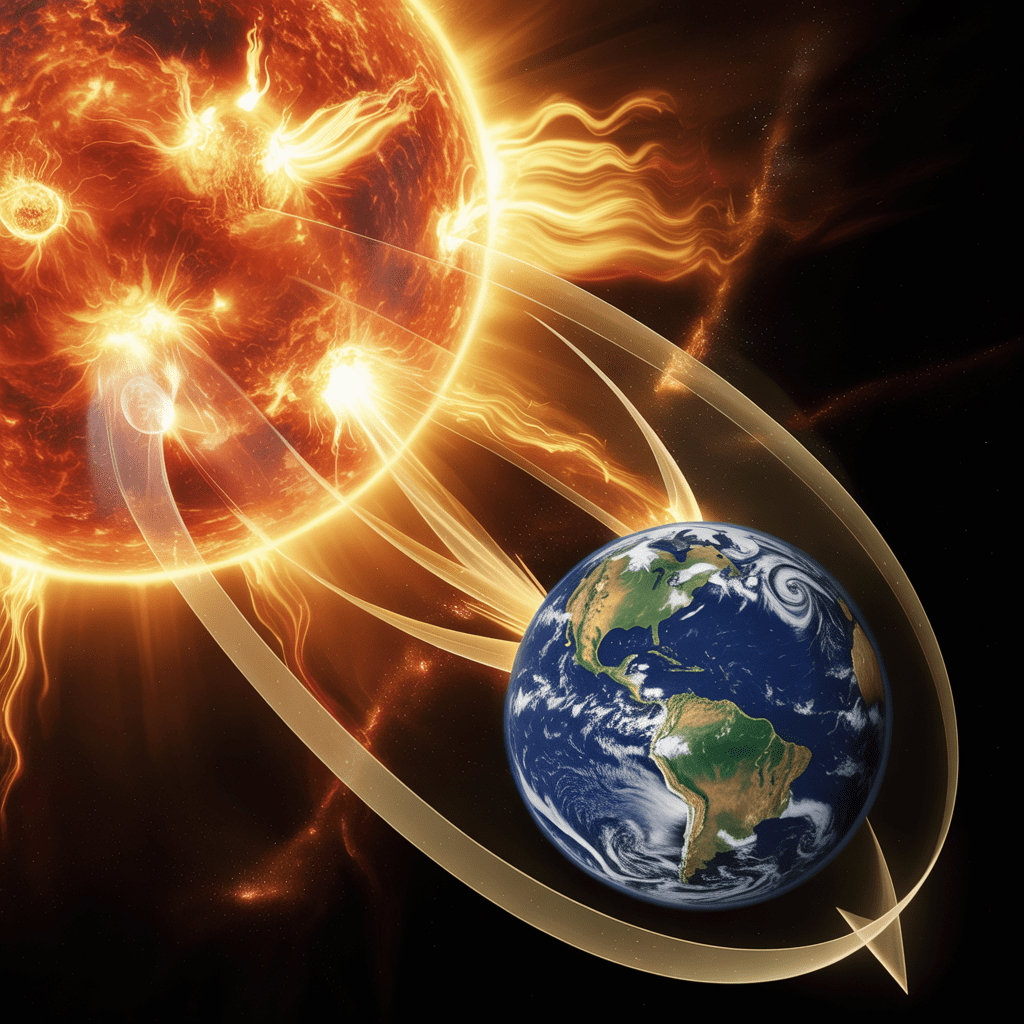

Solar Activity Affects Earth’s Spin and Length of Day

As always, post is in beta mode (work in progress)

The solar wind impacts the shape and behavior of the objects in our solar system. See Reference: Sunlight puts asteroids in a spin and Sunlight makes asteroids spin in strange waysDoes it also impact Earth’s spin?

Created with the assitance of: https://storm.genie.stanford.edu/article/earth-spin-length-of-day-and-sun-activity-since-1995-1318710

Further reading: Literature Review with Gemini Advance:

Summary

The relationship between Earth’s spin, the length of day (LOD), and solar activity has garnered significant attention from scientists since 1995, revealing crucial insights into the interplay between astronomical dynamics and climate change.

The average length of a day is conventionally defined as 24 hours, yet it is subject to subtle variations influenced by factors such as gravitational interactions, climatic conditions, and solar phenomena, which can reflect changes in Earth’s rotation rate over time.

These dynamics underscore the complexity of Earth’s motion, as well as the broader implications for our understanding of climate systems and environmental changes. Solar activity, primarily characterized by fluctuations in sunspots and solar flares, acts as a key driver of terrestrial conditions. With an approximately 11-year solar cycle, the Sun’s intensity and magnetic field dynamics impact space weather, which can affect satellite operations and communication systems on Earth.

Notably, while the total solar irradiance has shown minimal long-term changes since the Industrial Revolution, variations within the solar cycle have been linked to climate variability, leading to discussions regarding their potential influence on Earth’s rotational dynamics.

Research since 1995 has identified significant correlations between LOD (Length of Day) variations and solar activity, indicating that shifts in solar phenomena can have tangible effects on Earth’s rotation.

The identification of an 11-year signal within LOD variations has prompted further investigation into the underlying mechanisms at play, as scientists seek to disentangle the contributions of solar forces from other climatic influences, such as anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.

This ongoing exploration is critical for developing a comprehensive understanding of how solar dynamics shape Earth’s environment and impact climate patterns. The topic remains notable not only for its scientific implications but also for its relevance in contemporary discussions about climate change. While some studies suggest that solar variability could moderate global warming effects, the prevailing consensus indicates that human-induced factors are the dominant force driving recent climate trends, highlighting the importance of nuanced research into the interactions between solar activity and terrestrial systems.

As the field evolves, future research directions will aim to enhance observational techniques and integrate multi-instrument data to further clarify the intricate relationships between Earth’s rotation and solar dynamics.

Historical Context

The understanding of Earth’s rotation and solar activity has evolved significantly over the centuries, drawing connections between astronomical observations and terrestrial phenomena.

The Earth’s rotation period is approximately 24 hours concerning the Sun, but about 23 hours, 56 minutes, and 4 seconds when measured against distant stars, highlighting the complexity of our planet’s motion

Historical analysis indicates that the length of a day has gradually increased over time due to tidal forces exerted by the Moon, with a noted increase of approximately 2.3 milliseconds per century since the 8th century BCE

In the realm of solar activity, the Sun has been recognized as a primary driver of climate and environmental conditions on Earth. Ancient civilizations often revered the Sun, attributing various weather patterns to its behavior. For instance, as early as 400 BC, Meton of Athens observed a correlation between sunspot appearances and wetter weather, a notion later chronicled by Theophrastus

This early inquiry laid the groundwork for understanding the influence of solar activity on climate. The scientific investigation of solar cycles has gained traction since the 17th century when sunspot counts became a method for tracking solar activity. The 11-year solar cycle, characterized by periods of high and low activity linked to magnetic pole reversals, is particularly crucial. During periods of high solar activity, the Sun’s brightness can increase by about 0.1 percent compared to its lowest points in the cycle

Notably, the last century has witnessed an exceptional level of solar activity, peaking around the mid-20th century, which stands out in the context of the past 11,400 years

While there has been minimal long-term change in the Sun’s overall brightness since the Industrial Revolution, fluctuations in solar irradiance have nonetheless been associated with climate variability. These changes are now measured using advanced technology, including radio telescopes and Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI), which allow for precise monitoring of Earth’s rotation and orientation in relation to solar influences

As we continue to explore these dynamics, the interplay between solar activity and Earth’s rotation remains a crucial area of study for understanding both historical and contemporary climate patterns.

Measurement of Day Length

Variations in Day Length

Over the years, the length of the day has been subject to variations due to various factors, including gravitational influences and climatic conditions. The measurement of the length of day (LOD) can also fluctuate based on these influences, revealing a complexity that reflects changes in the Earth’s rotation rate

Research into intradecadal variations has shown that these changes can have significant implications for our understanding of Earth’s climate systems

Definition of Day Length

The length of a day is commonly defined as 24 hours, equivalent to 86,400 seconds. However, this measurement often refers to solar time, which is influenced by the Earth’s rotation relative to the Sun. The rotation of the Earth, measured in an inertial frame, is characterized by the sidereal day, which is approximately 23 hours, 56 minutes, and 4.1 seconds (or 86,164.1 seconds)

This means that in one complete rotation of the Earth, it turns about 360.986 degrees when adjusted for the extra movement needed to account for the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, resulting in an average of approximately 361.0 degrees per solar day

Measurement Techniques

Accurate measurement of day length has evolved significantly since the advent of space-based observational technology. Early measurements, such as those conducted by Samuel Langley in the late 19th century, laid the groundwork for understanding solar irradiance and its impact on the Earth’s environment

The introduction of instruments launched outside the Earth’s atmosphere, starting with the Nimbus-7 mission in 1978, has allowed for precise measurements of Total Solar Irradiance (TSI), which directly correlates to variations in solar activity

Continuous calibration of these instruments ensures the reliability of data, critical for assessing the relationship between solar activity and day length

[13]

Implications of Solar Activity

The interplay between solar activity and the Earth’s rotational dynamics is evident in the length of the day. Observations have indicated that solar phenomena, such as coronal mass ejections (CMEs), can affect the Earth’s atmosphere and, subsequently, its rotation

Variations in solar irradiance and the behavior of the polar vortex have also been linked to shifts in day length, highlighting the complex interactions between solar activity and terrestrial processes

Understanding the precise length of the day and its variations is crucial for various scientific disciplines, including climatology, astronomy, and geophysics, as it provides insights into the dynamics of the Earth’s rotation and its relationship with solar activity.

Sun Activity Overview

The Sun is the primary source of energy for Earth, influencing various terrestrial cycles and conditions. Solar activity encompasses changes in the Sun’s appearance and energy output, largely driven by its magnetic field dynamics. This magnetic activity operates through a solar dynamo mechanism, which can lead to phenomena such as sunspots and solar flares, both of which have significant implications for space weather and Earth’s climate.

Solar Flares

Solar flares are intense bursts of radiation emitted by the Sun, classified by their energy output. The classification ranges from A-class flares, which are the weakest, to X-class flares, which are the most powerful and can release energy equivalent to a billion hydrogen bombs.

The scale of intensity is logarithmic, similar to the Richter scale for earthquakes, meaning that each increase in class represents a tenfold increase in energy output. For example, an X-class flare is ten times stronger than an M-class flare.

Sunspots and Solar Cycles

Sunspots are dark regions on the Sun’s surface caused by intense magnetic activity, and they are indicative of the Sun’s magnetic field. The number of sunspots varies with the solar cycle, an approximately 11-year cycle of solar activity that alternates between solar maximum and minimum. During solar maximum, the number of sunspots and solar flares increases, while during solar minimum, these events become less frequent.

The Sun’s brightness also fluctuates slightly with these cycles, with a change of about 0.1 percent from maximum to minimum activity.

Effects on Earth

Solar activity, particularly during solar maximum, can influence space weather and potentially affect communication systems, satellite operations, and even power grids on Earth. Events like coronal mass ejections (CMEs), which often accompany solar flares, can cause geomagnetic disturbances when they collide with Earth’s magnetic field. This connection was solidified by research indicating that while solar flares were once thought to be the primary cause of geomagnetic disturbances, it is actually CMEs that are responsible for these effects.

Long-Term Trends

Since 1995, solar activity has shown variations in its intensity, contributing to discussions on climate change and global warming. While there have been fluctuations in solar activity, records indicate that long-term changes in the Sun’s overall brightness have been minimal since the start of the Industrial Revolution.

Studies have suggested that significant decreases in solar irradiance, such as during a Grand Solar Minimum, could potentially moderate global warming effects, although achieving substantial reductions in solar output appears unrealistic based on current understandings of solar physics.

Analysis of Day Length and Solar Activity (1995-Present)

The relationship between the Earth’s length of day (LOD) and solar activity has been a focal point of research since 1995. Studies have successfully identified an 11-year signal in the variation of LOD, which has been significantly linked to solar activity cycles

This correlation underscores the influence of solar dynamics on Earth’s rotational characteristics, with variations in LOD reflecting the underlying physical processes of solar phenomena.

Techniques for Analyzing Solar Activity

Various techniques have been developed to extract valuable information about the properties of magnetic clouds (MCs) and to enhance the understanding of their relationship with solar activity. However, assessing the accuracy of these methods using in situ data remains challenging. Research has compared MC properties across different approaches, such as magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) simulations and various fitting techniques

These studies highlight both the applicability of these methods in understanding MC structures and the limitations that need to be addressed for more reliable results.

Solar Irradiance Variability and its Implications

Long-term solar monitoring has successfully measured solar irradiance variability over the solar activity cycle. The total solar irradiance (TSI) and solar spectral irradiance (SSI) demonstrate a clear correlation with solar activity, varying continuously in response to solar events on time scales of days to months

These variations are influenced by active regions on the solar disk, which are associated with sunspots and enhanced radiation emissions. The modulation of solar activity is observable not only through the 11-year solar cycle but also due to the Sun’s 27-day rotational effects.

Cataloging Solar Events

To facilitate research into the impacts of solar activity on Earth, numerous catalogs of Earth-affecting transient events have been compiled. These include observed solar flares, coronal mass ejections (CMEs), and interplanetary coronal mass ejections (ICMEs) that have been tracked from their solar sources to their effects on Earth

Such resources serve as invaluable tools for understanding the complex interactions between solar events and their geoeffects, thereby enhancing the predictive capabilities for space weather phenomena.

Mechanisms of Influence

The influence of solar activity on Earth’s climate and weather patterns involves a complex interplay of mechanisms that can be broadly categorized into direct and indirect effects. These mechanisms can further be delineated into “Top-down” and “Bottom-up” processes, each contributing uniquely to the overall impact of solar variability.

Direct and Indirect Effects of Solar Activity

The direct effect of solar activity is primarily linked to variations in Total Solar Irradiance (TSI), which directly impacts global temperature. However, the influence of solar activity is also modulated by various indirect mechanisms that amplify these direct effects. In particular, the climate community emphasizes the importance of understanding how these mechanisms interact with atmospheric processes and oceanic energy content over time. For instance, while the Top-down mechanism may lead to immediate atmospheric responses, the Bottom-up mechanism relies on the gradual accumulation of energy, particularly in oceanic systems, before noticeable climatic effects manifest

Top-down and Bottom-up Mechanisms

Top-down Mechanism

The Top-down mechanism is characterized by its rapid response to solar forcing. Changes in solar output can induce swift alterations in atmospheric conditions, including shifts in radiative processes that can be detected within minutes to hours. This mechanism plays a crucial role in immediate weather phenomena and can be readily observed in the upper layers of the atmosphere

Bottom-up Mechanism

In contrast, the Bottom-up mechanism necessitates a build-up of solar forcing over extended periods to produce significant climatic changes. For example, large volcanic eruptions that cause substantial atmospheric aerosol emissions can demonstrate observable climatic effects within one to two years if the solar forcing is sufficiently large. However, the subtle influence of solar cycles on near-surface temperatures suggests that the amplification of solar forcing, whether through Top-down or Bottom-up channels, is relatively limited

Solar Wind and Magnetosphere Interactions

Another critical aspect of solar activity’s influence on Earth involves the interactions between the solar wind and the Earth’s magnetosphere. The solar wind, composed of charged particles, interacts with the magnetosphere to produce geomagnetic storms and various other geophysical phenomena. This dynamic interaction is influenced by factors such as the strength and orientation of the solar wind’s magnetic field, which can lead to significant energy transfer into the magnetosphere, thereby affecting terrestrial weather patterns and climate on a larger scale

Correlations Between Solar Activity and Atmospheric Parameters

Numerous studies have identified statistically significant correlations between solar activity, such as sunspot cycles, and atmospheric characteristics. However, the small magnitude of solar forcings is generally considered insufficient to account for these correlations, leading researchers to propose amplification mechanisms related to the solar magnetic fields. The intricate relationship between solar activity and atmospheric conditions demonstrates regional dependencies and variations in correlation, further complicating the understanding of solar-atmospheric influences

Implications of Findings

The relationship between solar activity and Earth’s rotation, including the length of the day, has been a subject of increasing interest in recent years. Studies have indicated that variations in solar irradiance can potentially influence climate patterns and, consequently, affect the dynamics of Earth’s rotation

For instance, changes in total solar irradiance, which can vary from 0.4 to 1.5 percent over extended periods, may correlate with significant climate events, suggesting a potential link between solar cycles and alterations in polar motion and rotation

Solar Activity and Climate Change

While the sun is a primary driver of the Earth’s climate system, recent consensus suggests that the impact of solar variability on contemporary climate change is minimal compared to greenhouse gas emissions

During the 2010s, average solar activity did not exceed levels seen in the 1950s, while global temperatures have notably increased, reinforcing the view that solar fluctuations alone cannot account for recent climate trends

This underlines the importance of considering human-induced factors when assessing changes in climate and, by extension, their effects on Earth’s rotation.

Polar Motion and Rotational Dynamics

Research has shown that climate-related changes, whether anthropogenic or natural, are significant contributors to alterations in Earth’s rotational dynamics. This includes shifts in polar motion, which can be affected by changes in ice mass distribution and atmospheric pressure fluctuations

As climate change continues to impact these factors, ongoing observations and studies aim to clarify the specific contributions of solar activity versus other climatic influences on the stability and movement of Earth’s rotational axis.

Long-Term Observations

Long-term monitoring and analysis of solar activity and its effects on the Earth have led to enhanced understanding of the potential mechanisms at play. For example, correlations have been observed between solar cycles and various weather phenomena, such as changes in storm tracks and atmospheric pressure patterns

Such findings highlight the complexity of the interactions between solar dynamics and Earth’s climate system, necessitating a multifaceted approach to future research in this area.

Future Research Directions

Enhanced Observation Techniques

To improve the understanding of solar activity and its influence on Earth’s rotation, future research should focus on the development and implementation of advanced observational techniques. Current methodologies predominantly rely on intensity-based methods for extracting coronal hole (CH) areas from solar observations. The incorporation of new algorithms and methodologies, such as improved fitting techniques and machine learning approaches, could lead to more accurate and reliable measurements of solar phenomena, including coronal mass ejections (CMEs) and their interactions

Integration of Multi-Instrument Data

A key direction for future studies involves the integration of data from a diverse range of solar and space weather monitoring instruments. Continuous observations from missions like the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), and the Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) have provided a wealth of information about solar activity. Future research can benefit from combining data from these instruments to enhance the understanding of the solar-terrestrial connection and the mechanisms driving solar irradiance variability and its subsequent effects on Earth’s climate

Investigating Long-Term Solar Variability

With the increasing duration of solar observations, it is essential to investigate the long-term variability of solar activity and its potential impact on Earth’s rotation and climate. Research should focus on analyzing historical data to correlate changes in solar output with significant terrestrial events, such as shifts in climate patterns and alterations in the length of day. Understanding the interplay between solar cycles and Earth’s environmental responses will help in predicting future trends and potential impacts on human technological systems

Addressing Reliability Issues in Current Models

While advancements have been made in modeling solar phenomena, significant reliability issues remain, particularly in the assessment of magnetic clouds (MCs) and CMEs. Future research should aim to address these limitations by validating models against in situ data and developing new techniques that can provide more robust predictions of solar events. Continued refinement of models, such as the ElEvoHI tool for CME prediction, is vital to enhance the accuracy of space weather forecasts that directly impact Earth

Focus on Transient Solar Events

Given the potential for transient solar events to cause adverse effects on Earth’s technological infrastructure, future research must prioritize the study of these events. The International Study of Earth-affecting Solar Transients (ISEST) project exemplifies the importance of collaborative efforts in understanding how short-term solar events impact the Earth’s space environment. Continued support for such initiatives will be crucial in developing effective strategies for mitigating the risks associated with these phenomena

By focusing on these future research directions, the scientific community can enhance the understanding of the intricate relationships between solar activity, Earth’s rotation, and overall climate variability.

Literature Review with Gemini Advance

A Structured Literature Review on Solar Activity Impact on Earth’s Spin and Length of Day

Introduction: Contextualizing Earth’s Rotation and Solar Influence

The Earth’s rotation, a fundamental astronomical parameter, is not a simple, constant motion. While it provides the basis for our timekeeping systems, its precise rate is subject to subtle yet measurable variations over a wide range of timescales, from diurnal to geological.1 The measure of this variation is known as the Length of Day (LOD), which is the time it takes for the Earth to complete one full rotation with respect to the Sun.1 Modern geodetic techniques, including satellite laser ranging and the use of atomic clocks, have enabled the measurement of LOD with millisecond-level precision, revealing a rich and complex signal that reflects the intricate dynamics of the entire Earth system.1 These small fluctuations, though imperceptible in daily life, are central to the fields of geophysics, climatology, and astronomy, as they provide a crucial record of the angular momentum exchange between the solid Earth and its fluid envelopes (atmosphere, oceans, and core) and also with external forces.3

Concurrent with the study of Earth’s rotational dynamics is the field of solar physics, which investigates the Sun’s activity and its effects on the solar system. Solar activity is driven by the Sun’s periodically reversing magnetic field, which operates through a solar dynamo mechanism.6 This activity is characterized by two primary periodicities: the approximately 11-year sunspot, or Schwabe, cycle and the 22-year magnetic, or Hale, cycle, which accounts for the complete reversal and return of the Sun’s magnetic polarity to its original state.7 In addition to these long-term cycles, the Sun also produces transient events, including solar flares, coronal mass ejections (CMEs), and high-speed streams of charged particles known as the solar wind.6 These phenomena are the primary drivers of space weather and are known to have significant impacts on near-Earth space and terrestrial systems.6

This literature review synthesizes the existing body of research on the direct and indirect links between solar activity and Earth’s rotational dynamics. It will explore the historical progression of thought, detail the primary physical mechanisms proposed to explain the relationship, and highlight the key debates and unresolved questions that define the current state of the field. This review aims to serve as a foundational resource for new research in this interdisciplinary domain by contextualizing past findings and identifying future research avenues.Foundational Research and Historical Empirical Correlations

2.1. Early Observations and the Recognition of a Relationship

The hypothesis of a connection between solar phenomena and terrestrial conditions is not a modern one; documented ideas about a link between sunspots and weather date back to at least 400 BC.14 However, the formal scientific investigation of a relationship between solar activity and Earth’s rotation began with the quantitative measurement of both phenomena. The discovery of the cyclical nature of sunspots by Samuel Heinrich Schwabe in 1843 7 provided a quantifiable solar forcing function that could be compared with records of Earth’s rotation. Early attempts to establish this connection laid the groundwork for modern, quantitative studies.15

2.2. Seminal Studies and the Identification of Key Periodicities

Over the decades, a number of seminal studies established compelling empirical correlations between LOD variations and key solar cycles. These findings moved the field beyond simple speculation to a more rigorous, quantitative analysis.

● The 22-Year Hale Cycle: Research has consistently identified a significant LOD oscillation with a period of approximately 22 years, which directly corresponds to the Hale magnetic cycle of the Sun. Kirov et al. (2002) found a direct correlation between the 22-year Hale cycle and LOD variations.15 This was supported by Chapanov, Vondrák, & Ron (2008), who noted that 22-year cycles of solar activity are a primary driver of various geophysical processes in the core-mantle, oceans, atmosphere, and geomagnetic field. These processes, in turn, are believed to excite their own oscillations, all synchronized with the 22-year solar cycle, ultimately leading to a 22-year LOD signal.9

● The 11-Year Schwabe Cycle: The more prominent 11-year sunspot cycle has also been a central focus of research since at least 1995.5 Mazzarella & Palumbo (1988) were among the first to suggest a tangible mechanism for this connection, proposing that the mean sea-level, which is influenced by the 11-year solar cycle’s effect on water evaporation due to total solar irradiance (TSI), could be a source of the 11-year LOD variation.9 Their work highlighted a correlation between LOD variations and sea-level changes, providing a tangible pathway for solar influence on a planetary scale.

● The 60-Year Cycle and Grand Minima: Extending beyond the 11-year and 22-year cycles, some studies have identified correlations on much longer timescales. Mazzarella (2007, 2008) and Mörner (2010, 2011) documented a close correlation between a 60-year cycle in solar activity and a similar signal in LOD, suggesting a longer-term, multi-decadal relationship.15 Mörner’s work further posited that Grand Solar Minima, such as the Spörer, Maunder, and Dalton Minima, corresponded to periods of accelerating Earth rotation, while Solar Maxima correlated with a rotational slowdown.15 This introduced a crucial, longer-term perspective to the solar-LOD relationship, connecting planetary rotation to periods of significant climatic changes, such as the Little Ice Ages.15

The existence of these diverse periodicities in LOD data (e.g., 6, 11, 22, 60 years) suggests that the LOD record is not just a measure of Earth’s overall rotation but a composite signal of various internal and external forcing functions on the Earth system. The challenge for researchers has been to deconvolve this signal to isolate the specific contribution of each component. This shifts the focus from merely establishing correlation to a deeper analysis of the underlying physics of each periodic signal. The LOD record is therefore not just a measure of rotation, but a fundamental geodetic data set for studying whole-planet dynamics.

Table 1 summarizes some of the key studies that have established empirical correlations between solar activity and Earth’s rotation.Table 1: Key Studies on Solar-LOD Correlations

Author(s) Year Key Periodicity Core Finding(s) Citation Mazzarella & Palumbo 1988 11-year Identified a link between 11-year LOD variations and mean sea-level, suggesting an indirect solar influence. 18 Kirov et al. 2002 22-year Found a direct correlation between the 22-year Hale cycle and LOD variations. 15 Abarca del Rio et al. 2003 Interannual Analyzed the connection between solar activity and LOD variability over the period 1831-1995. 19 Chapanov, Vondrák, & Ron 2008 22-year Confirmed that 22-year solar cycles excite geophysical processes that produce 22-year LOD oscillations. 9 Le Mouël et al. 2010 11-year, 5.5-year Proposed a link between solar activity, modulated zonal winds, and LOD variations. 21 Mörner 2010 60-year, Grand Minima Correlated long-term LOD fluctuations with Grand Solar Minima and Maxima, linking them to significant climate changes. 15 Proposed Physical Mechanisms of Solar-Geophysical Coupling

The observed correlations, while compelling, do not fully explain the physical mechanisms by which solar activity influences Earth’s rotation. The literature points to several distinct pathways of energy and momentum transfer.

3.1. The Role of the Atmosphere: Angular Momentum Exchange

The atmosphere is widely considered to be the most significant contributor to LOD variations on timescales of weeks to a few years.3 The principle of conservation of angular momentum dictates that any change in the axial component of the atmospheric angular momentum (AAM) must be accompanied by a corresponding and opposite change in the angular momentum of the solid Earth (crust and mantle).3 The coupling between the atmosphere and the solid Earth is strong, with a characteristic time constant of about 7 days due to surface friction.3

Solar activity can modulate this process. Variations in the total solar irradiance (TSI) and the solar wind are believed to influence large-scale atmospheric circulation.9 One key hypothesis suggests that the corpuscular activity of the solar wind causes a deceleration of zonal atmospheric circulation.15 This atmospheric slowdown acts as a torque, causing the solid Earth to accelerate its rotation to conserve total angular momentum.3 This chain-of-effect—from solar forcing to atmospheric circulation changes and then to LOD variations—is a central tenet of the solar-atmospheric-LOD hypothesis.15 The precise mechanisms by which solar UV irradiance or energetic particles influence atmospheric systems, such as the polar vortex, remain a subject of active research.53.2. Geomagnetic and Magnetospheric Forcing

A different class of mechanism involves the direct interaction of the Sun’s corpuscular emissions with Earth’s magnetic field. The solar wind, a continuous stream of charged particles from the Sun, and transient events like CMEs interact with Earth’s magnetosphere.11 This interaction, particularly when the solar wind’s magnetic field is directed southward (opposite to Earth’s field), can lead to a significant transfer of energy into the magnetosphere, causing geomagnetic storms.11 These storms result in intense electrical currents in the magnetosphere and ionosphere, which are known to exert a torque on the Earth’s solid body.11

The hypothesis is that this direct transfer of energy and momentum from the solar wind to the Earth’s magnetic field and atmosphere acts as a direct rotational forcing function.15 Evidence has indicated that high solar activity and its associated geomagnetic effects correlate with a deceleration of Earth’s rotation, while periods of low solar activity correlate with acceleration.15 The complex nature of these magnetospheric currents, however, is not yet fully understood and represents a significant gap in the literature.133.3. Thermospheric Drag as a Rotational Brake

Another physical pathway for solar influence is through atmospheric drag. During periods of high solar activity, the increased flux of solar radiation and particles leads to the thermal heating and expansion of the upper atmosphere, particularly the thermosphere and ionosphere.13 This expansion increases atmospheric density at low-Earth orbit (LEO) altitudes, causing a significant increase in drag on satellites.27 This drag force, which acts opposite to the direction of motion, requires frequent orbital boosts for spacecraft like the International Space Station to counteract the deceleration.28 While this effect is most pronounced on orbiting objects, it also represents a tangible mechanism by which solar energy could transfer momentum and exert a decelerating force on the Earth’s overall rotation.

- The Core-Mantle vs. Solar Forcing Debate: A Central Conflict

4.1. The Role of Core-Mantle Coupling

While external solar forcing is a significant contributor to LOD variations, the dominant influence on decade-to-millennial timescales is widely attributed to internal Earth dynamics, specifically the interaction between the fluid outer core and the solid mantle.3 Mechanisms for this coupling include:

● Gravitational Coupling: The convection of the liquid outer core creates time-variable density inhomogeneities, which can be thought of as “blobs” moving randomly, like in a lava lamp.29 These inhomogeneities produce a gravitational field that is not perfectly uniform. This gravitational field then exerts a torque on density anomalies within the mantle and crust, changing the mantle’s rotation state.29 This mechanism is a suspected cause for observed rotational changes on millennial timescales.29

● Electromagnetic and Viscous Coupling: Electromagnetic forces and fluid-to-solid friction at the core-mantle boundary (CMB) are also thought to be crucial for the exchange of angular momentum. These interactions are proposed to be responsible for the prominent 6-year and decade-scale LOD fluctuations.3 The precise nature of the torques at work is still a subject of ongoing debate.304.2. The Overlap and the Challenge of Attribution

The central conflict in the literature arises from the fact that both external solar forcing and internal core-mantle coupling can produce signals on similar timescales, making it difficult to definitively attribute a specific LOD fluctuation to a single source.3 For example, the 22-year signal in the LOD record could be a direct result of solar activity 9 or a core-mantle process that is itself excited or modulated by solar forcing. The signals are conflated, meaning that simple correlational studies, while useful for establishing a link, cannot provide the final answer on causation. This reality underscores the need for a more sophisticated, physically-based modeling approach that can account for and separate the influences of these distinct forcing functions.

4.3. The Emerging Anthropogenic Signal

Adding another layer of complexity to the deconvolution problem is the emerging evidence that human activities are now measurably influencing Earth’s rotation.32 The redistribution of mass on the planet’s surface, particularly through the construction of large dams and the rapid loss of glaciers and ice sheets due to climate change, is causing a measurable shift in the Earth’s poles (polar wander) and a subtle slowdown of its rotation.32 One study estimated that human-linked shifts in ice and groundwater are slowing Earth’s rotation at a rate of 1.33 milliseconds per century.32 This new, significant source of forcing makes the analysis of historical and modern LOD data even more challenging, as researchers must now deconvolve natural signals from these increasingly influential anthropogenic ones.32

Table 2 provides a comparison of the various internal and external forcing mechanisms that contribute to the observed variations in Earth’s rotation.

Table 2: Comparison of Forcing Mechanisms on Earth’s Rotation

Forcing Mechanism Primary System(s) Involved Typical Timescale(s) of Influence Proposed Causal Link to LOD

Tidal Friction Earth-Moon System, Oceans Secular, Multi-millennial Gravitational torque from the Moon and Sun slows down Earth’s rotation.

Core-Mantle Coupling Core, Mantle, Geomagnetic Field Decadal, Sub-decadal (e.g., 6-year cycle) Gravitational and electromagnetic torques transfer angular momentum between the core and mantle.

Atmospheric Angular Momentum (AAM) Atmosphere, Solid Earth Weeks to a few years Exchange of angular momentum between the atmosphere and the solid Earth through surface friction.

Solar Corpuscular Forcing Solar Wind, Magnetosphere, Atmosphere 11-year, 22-year, Transient Transfer of angular momentum via geomagnetic storms and modulation of atmospheric circulation.

Anthropogenic Mass Redistribution Hydrosphere, Cryosphere Millennial, Recent decades Shifts in mass (e.g., dams, ice melt) alter the Earth’s moment of inertia, changing its rotation.- Gaps in the Literature and Future Research Directions

5.1. The Non-Stationary Nature of Correlations

A significant problem in solar-terrestrial research is the lack of stability in the observed correlations. Studies have noted that the relationship between sunspot numbers and various atmospheric and geophysical parameters is not stationary; it can “strengthen, weaken, disappear, and even change sign depending on the time period”.14 This lack of stationarity suggests that simple linear models are insufficient and that the underlying physics is either highly non-linear or that the relationship is mediated by additional, unmodeled factors. A deeper understanding of these temporal variations in the solar-terrestrial connection, including the physical reasons for their reversals, is a critical gap that must be addressed.14

5.2. Unresolved Questions in Solar Physics and Space Weather

The problem of understanding the solar-LOD connection is not solely on the terrestrial side. Significant unknowns exist in solar physics itself, which hamper our ability to predict the solar forcing function with high fidelity.33 It is still not fully understood how the Sun generates its periodically reversing magnetic field, which is the engine of all solar activity.8 The mechanisms behind Grand Solar Minima, which correspond to periods of significant terrestrial change, are also not yet fully explained.33

Furthermore, the ability to predict the characteristics of geomagnetic storms, such as the direction of the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) B-field, remains a key challenge for space weather forecasting.25 The existence of phenomena like the “Gnevyshev gap,” a mysterious dip in activity during the peak of solar maxima, has been noted for decades but is not yet completely clarified, despite its potential relevance for space weather forecasting.34 Improved space weather prediction is contingent on addressing these foundational gaps in our knowledge of the solar dynamo and transient solar events.265.3. The Challenge of “Whole Planet Coupling”

The literature consistently points to the need for a holistic “whole planet coupling” approach to fully comprehend the dynamics of Earth’s rotation.35 The Earth is a complex, interacting system where a change in one component, such as the core, affects another, such as the mantle.29 This, in turn, can be influenced by an external factor like the Sun. A change in solar activity affects the atmosphere, which then affects the solid Earth and its spin.9 Existing models often focus on one or two of these mechanisms in isolation, but a true understanding requires moving beyond these siloed approaches. The challenge is to build comprehensive models that integrate the complex interactions between the core, mantle, atmosphere, oceans, and external solar forcing.9 This is a massive computational and theoretical task that requires bridging disciplinary divides and is central to the future of this field.

5.4. Proposed Future Research Avenues

Based on the identified gaps and challenges, several key avenues for future research are apparent:

● Integrated Modeling: New research should focus on developing next-generation models that can simultaneously account for and deconvolve the natural (solar, core-mantle) and anthropogenic signals in high-precision LOD data.32 These models must treat the Earth as a single, interacting system to move beyond simple statistical correlations to a true physical understanding.

● Improved Solar Forcing Proxies: Future work should aim to improve solar cycle and space weather prediction models by incorporating a wider range of solar observational data beyond just sunspot numbers, which are an oversimplified proxy.36

● Targeted Data Acquisition: Targeted missions and experiments are needed to gather higher-resolution data on core-mantle dynamics and magnetospheric-ionospheric currents, which remain poorly understood.28

● Non-linear Analysis: Research should explore the physical mechanisms behind the “non-stationary” correlations and the “reversals of sign” that have been observed.14 This may require the use of machine learning or novel non-linear analysis techniques on long-term data sets.- Conclusion

The literature provides compelling and extensive evidence for a strong empirical correlation between solar activity and variations in Earth’s rotation, particularly on decadal and multi-decadal timescales. However, the causal links are not fully understood and remain a central subject of active debate. The LOD record is a composite signal, simultaneously reflecting external forces from the Sun and internal forces from the core-mantle system, as well as increasingly significant anthropogenic factors. The central challenge for the field is to move beyond the identification of simple correlations and to tackle the fundamental problem of disentangling these multiple, interacting forcing functions.

The LOD record, now more than ever, is a crucial geodetic variable for monitoring the health and dynamics of the entire Earth system. The future of research in this area lies in the development of sophisticated, integrated models that treat the Earth-Sun system as a unified whole. This will require new, high-resolution data, advanced modeling techniques, and continued interdisciplinary collaboration to fully resolve one of the most intriguing questions in geophysics.

Works cited- Earth’s rotation – Wikipedia, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Earth%27s_rotation

- Earth Spun Faster Today. Here’s How We Know. – Science Alert, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.sciencealert.com/earth-spun-faster-today-heres-how-we-know

- Day length fluctuations – Wikipedia, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Day_length_fluctuations

- Day – Wikipedia, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Day

- Solar Activity Affects Earth’s Spin and Length of Day – Circular …, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://circularastronomy.com/2025/07/30/solar-activity-affects-earths-spin-and-length-of-day/

- ESA – The solar cycle, a heartbeat of stellar energy – European Space Agency, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/The_solar_cycle_a_heartbeat_of_stellar_energy