Circular Astronomy

Twitter List – See all the findings and discussions in one place

-

The Mysterious Discovery of JWST That No One Saw Coming

Are We Inside a Cosmic Whirlpool? Recent JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES) observations of mysterious cosmological anomalies in the rotational patterns of galaxies challenge our understanding of the universe and reveal surprising connections to natural growth patterns.

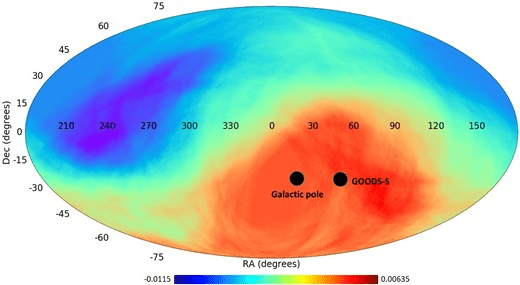

The rotation of 263 galaxies has been studied by Lior Shamir of Kansas State University, with 158 rotating clockwise and 105 rotating counterclockwise. The number of galaxies rotating in the opposite direction relative to the Milky Way is approximately 1.5 times higher than those rotating in the same direction.

New Cosmological anomalies that challenge our cosmological models and would have angered Einstein.

This observation challenges the expectation of a random distribution of galaxy rotation directions in the universe based on the isotropy assumption of the Cosmological Principle.

This is certainly not something Einstein would have liked to hear during his lifetime, but it would have excited Johannes Kepler.

What does this mean for our cosmological models, and why would it make Johannes Kepler happy?

The 1.5 ratio in galaxy rotation bias is intriguingly close to the Golden Ratio of 1.618. The Golden Ratio was one of Johannes Kepler’s two favorites. The astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) referred to the Golden Ratio as one of the “two great treasures of geometry” (the other being the Pythagorean theorem). He noted its connection to the Fibonacci sequence and its frequent appearance in nature.

What is the Fibonacci sequence?

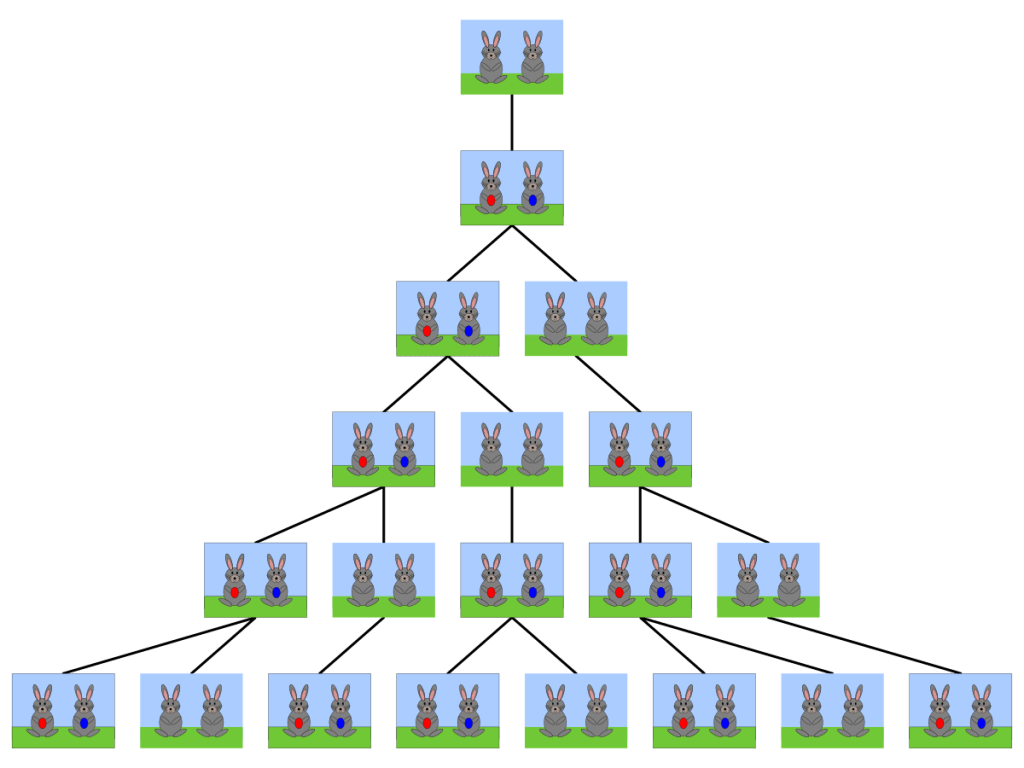

The Italian mathematician Leonardo of Pisa, better known as Fibonacci, introduced the world to a fascinating sequence in his 1202 book Liber Abaci (The Book of Calculation). This sequence, now famously known as the Fibonacci sequence, was presented through a hypothetical problem involving the growth of a rabbit population.

The growth of a rabbit population and why it matters?

Fibonacci posed the following question: Suppose a pair of rabbits can reproduce every month starting from their second month of life. If each pair produces one new pair every month, how many pairs of rabbits will there be after a year?

The solution unfolds as follows:

- In the first month, there is 1 pair of rabbits.

- In the second month, there is still 1 pair (not yet reproducing).

- In the third month, the original pair reproduces, resulting in 2 pairs.

- In the fourth month, the original pair reproduces again, and the first offspring matures and reproduces, resulting in 3 pairs.

Image Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FibonacciRabbit.svg

This pattern continues, with each new generation adding to the total, where each term is the sum of the two preceding terms.

The Fibonacci sequence generated is: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, …

While this idealized model of a rabbit population assumes perfect conditions—no sickness, death, or other factors limiting reproduction—it reveals a growth pattern that approaches the Golden Ratio as the sequence progresses. The ratio is determined by dividing the current population by the previous population. For example, if the current population is 55 and the previous population is 34, based on the Fibonacci sequence above, the ratio of 55/34 is approximately 1.618.

However, in reality, the growth rate of a rabbit population would likely fall below this mathematical ideal ratio due to natural constraints.Yet, this growth (evolutionary) pattern appears quite often in nature, such as in the growth patterns of succulents.

The growth patterns in succulents often follow the Fibonacci sequence, as seen in the arrangement of their leaves, which spiral around the stem in a way that maximizes sunlight exposure. This spiral phyllotaxis reflects Fibonacci numbers, where the number of spirals in each direction typically corresponds to consecutive terms in the sequence.

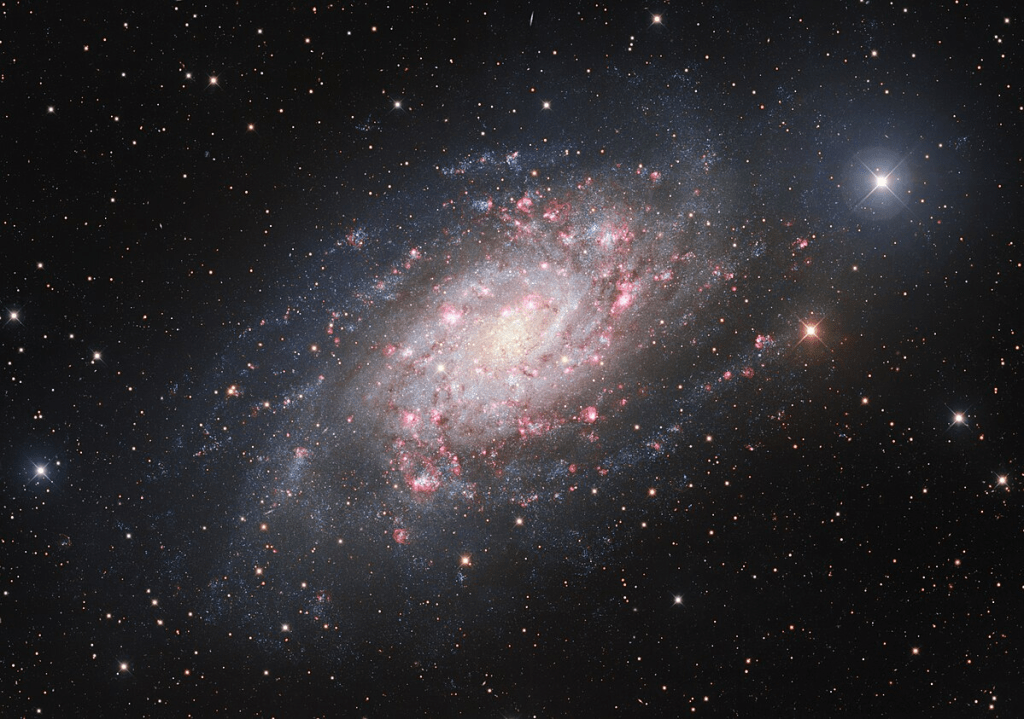

Spiral galaxies exhibit a similar growth (evolutionary) pattern in their spiral arms.

Spiral galaxies, like the Milky Way, display strikingly similar growth patterns in their spiral arms, where new stars are continuously formed and not in the center of the galaxy.

Image Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_Galaxy_of_Birth_and_Death.jpg

Returning to the observations and research conducted by Lior Shamir of Kansas State University using the JWST.

The most galaxies with clockwise rotation are the furthest away from us.

The GOODS-S field is at a part of the sky with a higher number of galaxies rotating clockwise

Image Source: Figure 10 https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staf292

“If that trend continues into the higher redshift ranges, it can also explain the higher asymmetry in the much higher redshift of the galaxies imaged by JWST. Previous observations using Earth-based telescopes e.g., Sloan Digital Sky Survey, Dark Energy Survey) and space-based telescopes (e.g., HST) also showed that the magnitude of the asymmetry increases as the redshift gets higher (Shamir 2020d).” Source: [1]“It becomes more significant at higher redshifts, suggesting a possible link to the structure of the early universe or the physics of galaxy rotation.” Source: [1]

Could the universe itself be following the same growth patterns we see in nature and spiral galaxies?

This new observation by Lior Shamir is particularly intriguing because, if we were to shift the perspective of our standard cosmological model—from one based on a singularity (the Big Bang ‘explosion’), which is currently facing a lot of challenges [2], to a growth (evolutionary) model—we would no longer be observing the early universe. Instead, we would be witnessing the formation of new galaxies in the far distance, presenting a perspective that is the complete opposite of our current worldview (paradigm).

NEW: Massive quiescent galaxy at zspec = 7.29 ± 0.01, just ∼700 Myr after the “big bang” found.

RUBIES-UDS-QG-z7 galaxy is near celestial equator.

It is considered to be a “massive quiescent galaxy’ (MQG).

These galaxies are typically characterized by the cessation of their star formation.

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/adab7a

The rotation, whether clockwise or counterclockwise, has not yet been observed.Reference

The distribution of galaxy rotation in JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey

Lior Shamir

[1 ] https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/538/1/76/8019798?login=false

The Hubble Tension in Our Own Backyard: DESI and the Nearness of the Coma Cluster

Daniel Scolnic, Adam G. Riess, Yukei S. Murakami, Erik R. Peterson, Dillon Brout, Maria Acevedo, Bastien Carreres, David O. Jones, Khaled Said, Cullan Howlett, and Gagandeep S. Anand

[2] https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2041-8213/ada0bd

Reading Recommendation:

The Golden Ratio, Mario Livio, 2002

Mario Livio was an astrophysicist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, which operates the Hubble Space Telescope.

RUBIES Reveals a Massive Quiescent Galaxy at z = 7.3

Andrea Weibel, Anna de Graaff, David J. Setton, Tim B. Miller, Pascal A. Oesch, Gabriel Brammer, Claudia D. P. Lagos, Katherine E. Whitaker, Christina C. Williams, Josephine F.W. Baggen, Rachel Bezanson, Leindert A. Boogaard, Nikko J. Cleri, Jenny E. Greene, Michaela Hirschmann, Raphael E. Hviding, Adarsh Kuruvanthodi, Ivo Labbé, Joel Leja, Michael V. Maseda, Jorryt Matthee, Ian McConachie, Rohan P. Naidu, Guido Roberts-Borsani, Daniel Schaerer, Katherine A. Suess, Francesco Valentino, Pieter van Dokkum, and Bingjie Wang (王冰洁)

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/adab7a

Appendix Spiral Galaxies:

Spiral galaxies are known for their stunning and symmetrical spiral arms, and many of them exhibit patterns that approximate logarithmic spirals, which are mathematically related to the Golden Ratio. While not all spiral galaxies perfectly follow the Golden Ratio, some exhibit spiral arm structures that closely resemble this pattern. Here are some notable examples of spiral galaxies with logarithmic spiral patterns:

1. Milky Way Galaxy

- Our own galaxy, the Milky Way, is a barred spiral galaxy with arms that approximate logarithmic spirals. The four primary spiral arms (Perseus, Sagittarius, Scutum-Centaurus, and Norma) follow a logarithmic pattern, though not perfectly aligned with the Golden Ratio.

2. M51 (Whirlpool Galaxy)

- The Whirlpool Galaxy is one of the most famous examples of a spiral galaxy with well-defined logarithmic spiral arms. Its arms are nearly symmetrical and exhibit a pattern that closely resembles the Golden Ratio.

3. M101 (Pinwheel Galaxy)

- The Pinwheel Galaxy is a grand-design spiral galaxy with prominent and well-defined spiral arms. Its structure is often cited as an example of a logarithmic spiral in astronomy.

4. NGC 1300

- NGC 1300 is a barred spiral galaxy with a striking logarithmic spiral pattern in its arms. It is often studied for its near-perfect spiral structure.

5. M74 (Phantom Galaxy)

- The Phantom Galaxy is another grand-design spiral galaxy with arms that follow a logarithmic spiral pattern. Its symmetry and structure make it a textbook example of this phenomenon.

6. NGC 1365

- Known as the Great Barred Spiral Galaxy, NGC 1365 has a prominent bar structure and spiral arms that exhibit a logarithmic pattern.

7. M81 (Bode’s Galaxy)

- Bode’s Galaxy is a spiral galaxy with arms that follow a logarithmic spiral structure. It is one of the brightest galaxies visible from Earth and a popular target for astronomers.

8. NGC 2997

- This galaxy is a grand-design spiral galaxy with arms that closely resemble logarithmic spirals. It is located in the constellation Antlia.

9. NGC 4622

- Known as the “Backward Galaxy,” NGC 4622 has a unique spiral structure with arms that follow a logarithmic pattern, though its rotation direction is unusual.

10. M33 (Triangulum Galaxy)

- The Triangulum Galaxy is a smaller spiral galaxy with arms that exhibit a logarithmic spiral structure. It is part of the Local Group, along with the Milky Way and Andromeda.

-

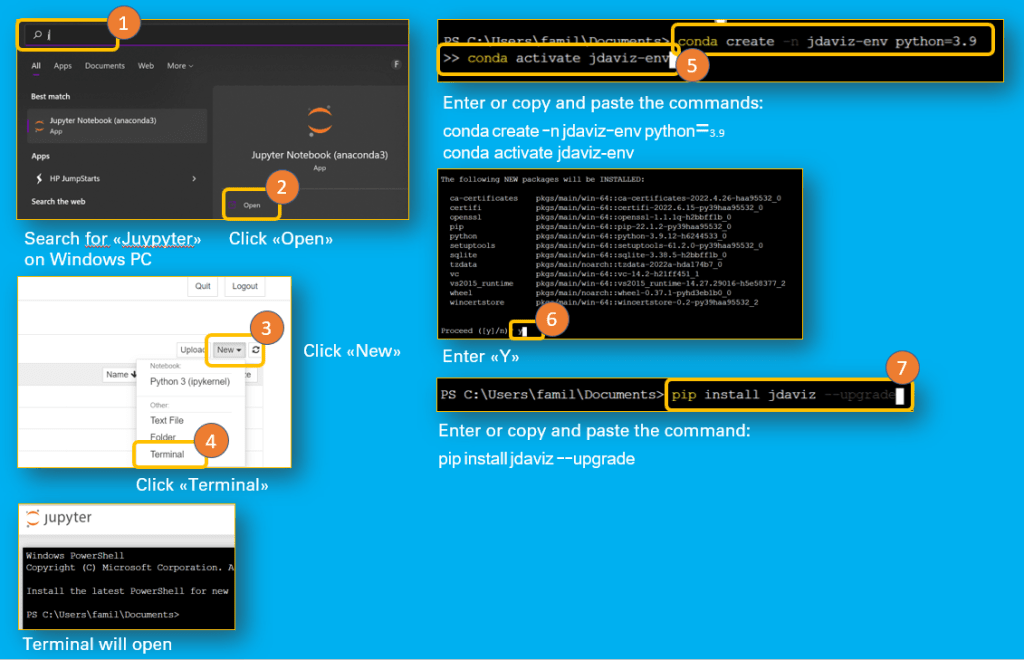

How to Download, View, And Edit Images from the James Webb Space Telescope with Jdaviz and Imviz

Like to comfortably view and edit images from the Jamew Webb Space Telescope like an astronomer ?

Then follow this step by step cheatsheet guides if you are using windows on a PC .

Main Software Components

There are three key software components required:

- Microsoft C++ 14

- Jupyter Notebook (Python)

- Jdaviz

Additonal

- MAST Token to be able to download the images with Imviz.

Prerequsites:

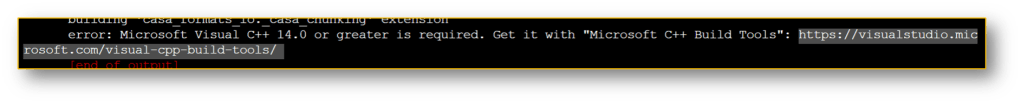

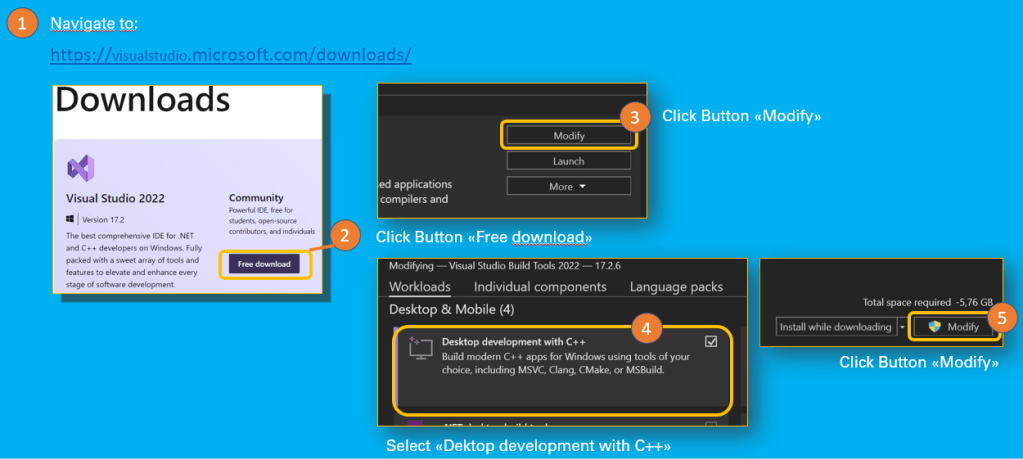

Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater

error: Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater is required If Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater is not installed, the installation of Jdaviz will fail. Without Jdaviz the downloaded images from the James Webb Space Telescope cannot be edited.

How to install Microsoft Visual C++

- Navigate to: https://visualstudio.microsoft.com/downloads/

- Download Visual Studio 2022 Community version

- Follow the instructions in this post: Install C and C++ support in Visual Studio | Microsoft Docs

Cheatsheet: Install Visual Studio 2022 MAST Token

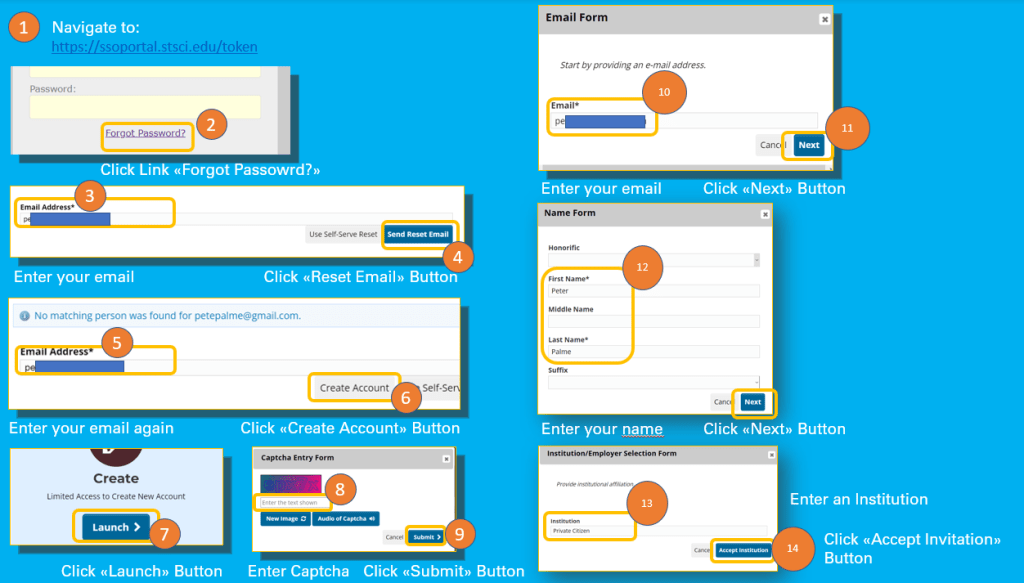

- Navigate to https://ssoportal.stsci.edu/token

If you do not have not an account yet, please follow below steps to create your account:

- Click on the Forgotten Password? link

- Enter your email Adress

- Click Send Reset Email Button

- Click Create Account Button

- Click Launch Button

- Enter the Captcha

- Click Submit Button

- Enter your email

- Click Next Button

- Fill in the Name Form

- Click Next Button

- Fill in the Insitution (e.g. Private Citizen or Citizen Scientist)

- Click Accept Institution Button

- Enter Job Title (whatever you are or like to be ;-))

- Click Next Button

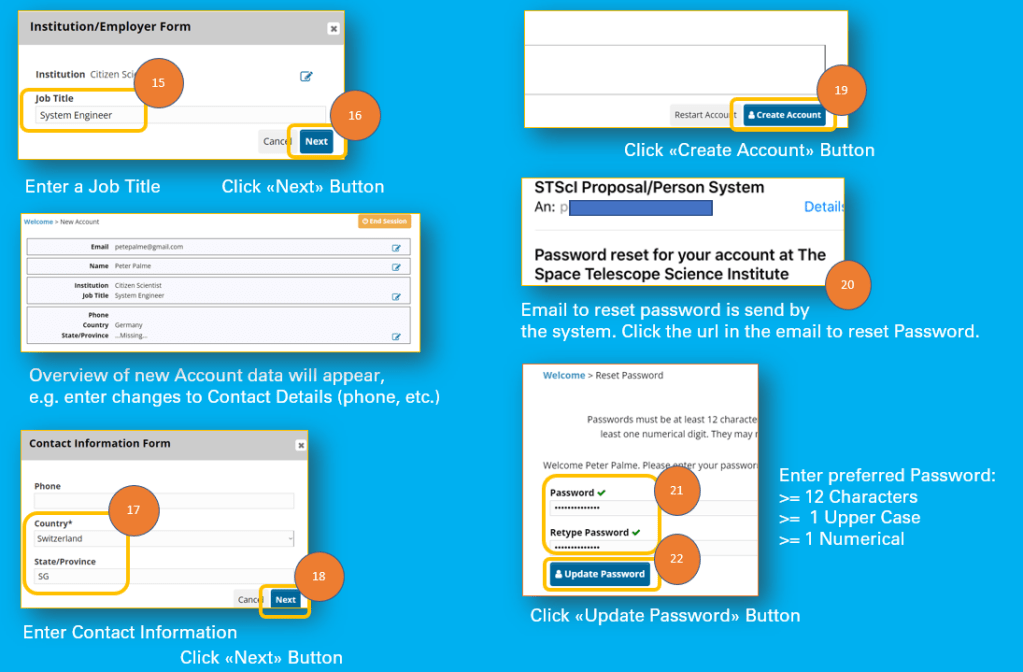

- New Account Data for your review is presented, in case of missing contact data, step 17 might be necessary

- Fill in Contact Information Form

- Click Next Button

- Click Create Account Button

- In your email account open the reset password emal

- Click on the link

- Enter Password

- Enter Retype Password

- Click Update Password

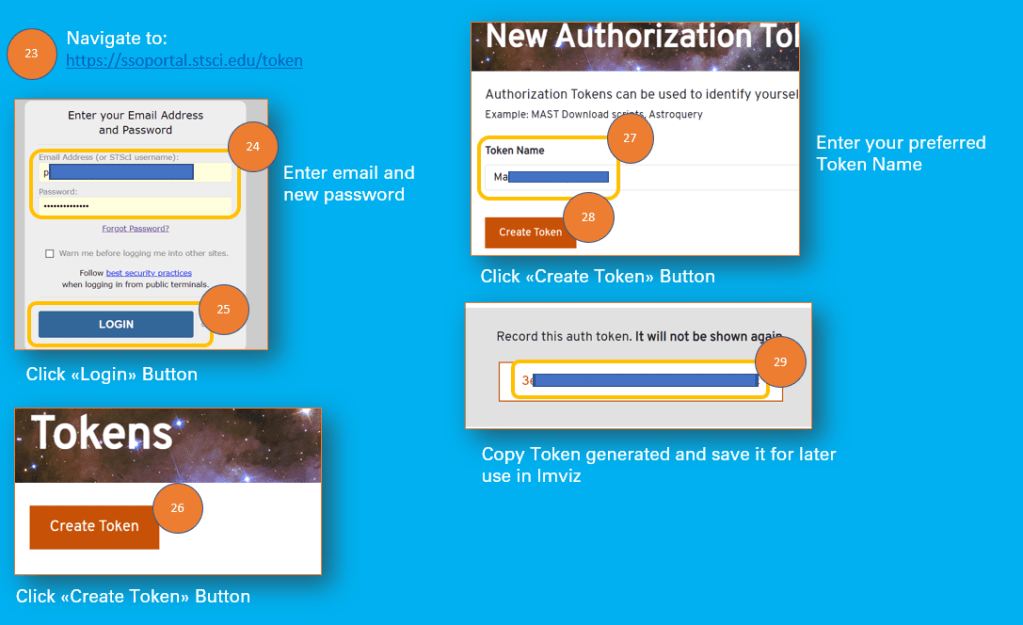

- Navigate to https://ssoportal.stsci.edu/token

- Now log on with your email and new account password

- Click Create Token Button

- Fill in a Token Name of your choice

- Click Create Token Button

- Copy the Token Number and save it for later use in Imviz to download the images from the James Webb Space Telescope

Quite a lot of steps for a Token.

Cheatsheet: Create MAST Account

Cheatsheet: Set Passord for new Account

Cheatsheet: Create MAST Token for use in Imviz Jupyter Notebook

Jupyter notebook comes with the ananconda distribution.

- Navigate to: https://www.anaconda.com/products/distribution#windows

- Follow the instructions at: https://docs.anaconda.com/anaconda/install/windows/

Install Jdaviz

- Navigate to: Installation — jdaviz v2.7.2.dev6+gd24f8239

- Open the Jupyter Notebook

- Open Terminal from Jupyter Notebook

- Follow the instruction in: Installation — jdaviz v2.7.2.dev6+gd24f8239

Cheatsheet: Install Jdaviz How to use IMVIZ

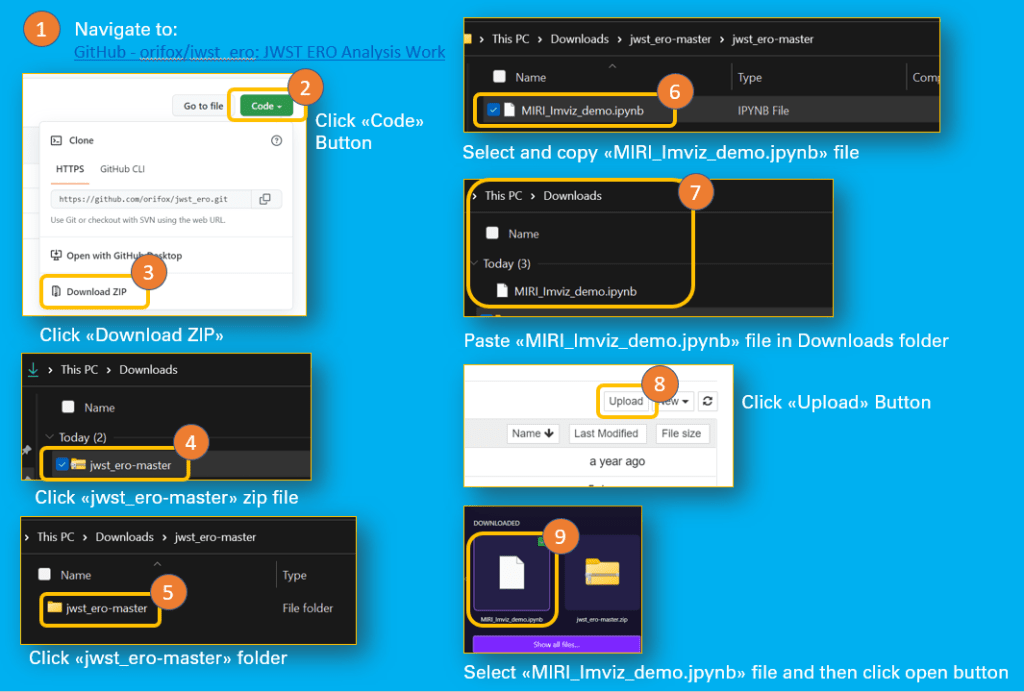

Imviz is installed together with Jdaviz.

Following steps to take in order to use Imviz:

- Navigate to: GitHub – orifox/jwst_ero: JWST ERO Analysis Work

- Click Code Button

- Click Download Zip

- If you do not have unzip, then the next steps might work for you:

- In Download Folder (PC) click the jwst_ero master zip file

- Then click on the folder jwst_ero master

- Copy file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb

- Paste the file in the download folder

- Open Jupyter notebook

- Click Upload Button

- Select the file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb

- Click Open Button

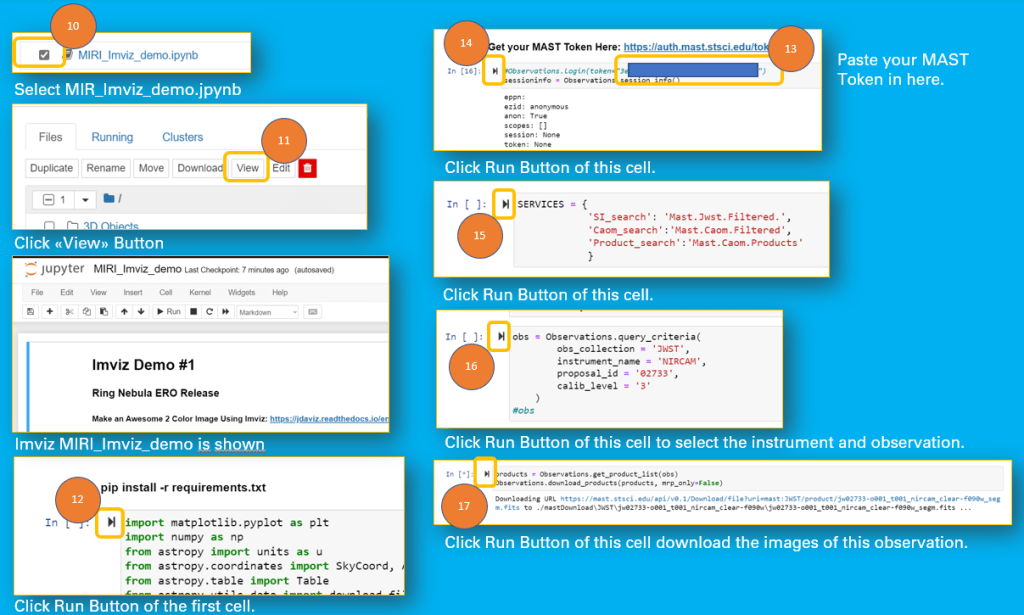

- Select the file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb in the Jupyter Notebook file list

- Click View Button

- Click Run Button First Cell

- Paste MAST Token in next cell

- Click Run Button of this Cell

- Click then Run Button of next Cell

- Click Run Button of the following Cell

- Click Run Button of the next Cell to download the images

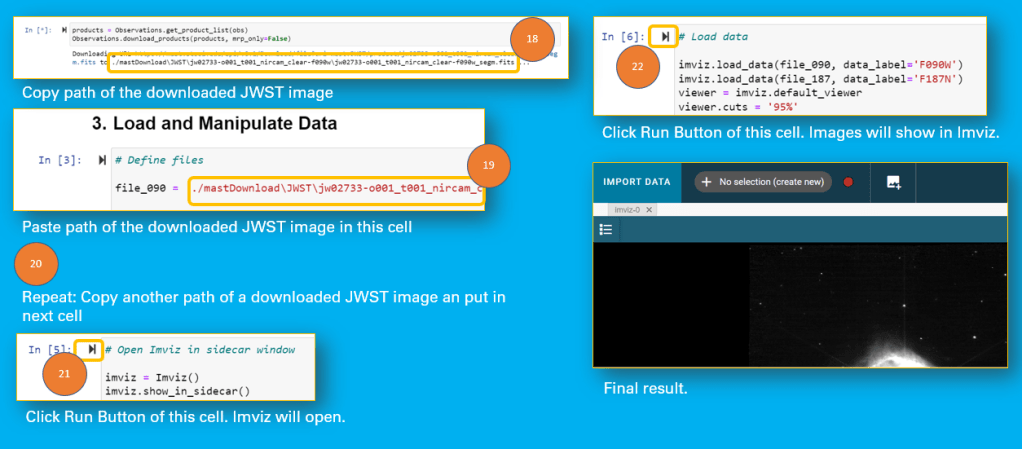

- Copy the link to the downloaded image file

- Past link into the First Cell in 3. Load and Manipulate Data

- Do the same in the next Cell

- Click Run Button of the Cell to open Imviz

- Click Run Button on the next Cell to load images in Imviz

Cheatsheet: Upload MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb in Jupyter notebook Now all set to download the images of the JWST observation:

Cheatsheet: Download JWST images with Imviz And now all is set to open and edit the images in Imviz

Cheatsheet: Open Images in Imviz And finally you are ready to follow the video tutorials in order to learn how to use Imviz to manipulate the JWST images.

Video Tutorials for Imviz:

And this is the master Ori Fox of the Imviz demo notebook file if you like to follow him on Twitter

-

Time for a new scientific debate – Accretion vs Convection

To what degree is gravity needed to form structures in space? While many believe that celestial bodies (stars, planets, moons, meteoroids) can only form through gravitational attraction in the vacuum of space, I believe that these bodies form through a thermodynamic process similar to the formation of hydrometeors (e.g., hail). This is because our solar system possesses a boundary layer, a discovery made by the Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) mission in 2013.

In simple terms: Planets, moons, and small bodies are formed within convection cells created by the jet streams of a young sun, under the influence of strong magnetic fields.

Recently, a new paper introduced quantum models in which gravity emerges from the behavior of qubits or oscillators interacting with a heat bath.

More details and link to the research paper: On the Quantum Mechanics of Entropic Forces

https://circularastronomy.com/2025/10/09/entropic-gravity-explained-how-quantum-thermodynamics-could-replace-gravitons/ -

Surprise – Comets Are Showing A Range of Icy Structures

Using its Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has the capability to measure the structure of ice.

Likely a new challenge for the accretion model. Expected was either crystalline or amorphous ice in comets depending on the temperature in the protoplanetary disk.

-

Binary Star PDS 144B in Scorpius has a Proplyd – Ionized Protoplanetary Disk

Explanation of a Proplyd – ionized protoplanetary disk PDS 144B is part of a binary star system known as PDS 144, which is notable for being the first confirmed Herbig Ae/Be binary system (2012) where both stars drive jets.

Herbig Ae/Be stars are a class of pre-main-sequence stars that are more massive than T Tauri stars and are characterized by their emission lines and association with reflection nebulae.

PDS 144B is part of the binary star system PDS 144, which features two Herbig Ae stars, PDS 144N (North) and PDS 144S (South). The protoplanetary disk around PDS 144B (PDS 144N) is particularly notable for its geometry and composition.

Key Features of the PDS 144B Protoplanetary Disk:

- Geometry: The disk around PDS 144B is observed nearly edge-on, within 5° of perfect alignment, which is a common feature shared with other systems like HH 30 and HK Tau B. This orientation allows for detailed studies of the disk’s structure and composition.

- Size and Structure: The disk has a radius of approximately 58 AU and a height of about 22 AU, making it relatively compact compared to other Herbig Ae disks like AB Aur or HD 100546, which are much larger. The smaller size may be due to dynamical truncation from interactions with the companion star, PDS 144S.

- Composition: The disk of PDS 144B contains polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are detected due to the disk’s flared structure that allows for UV irradiation of the dust. This is in contrast to the disk around PDS 144S, which lacks PAH emission, likely due to a flatter disk geometry that prevents UV irradiation.

- Inclination and Visibility: The inclination of the disk around PDS 144B is such that it is visible in direct light imagery, unlike many other circumstellar disks at similar inclinations. This visibility allows for detailed photometric and spectroscopic studies.

Other Examples of Proplyds .- ionized protoplanetary disks Overall, the PDS 144B protoplanetary disk provides a valuable opportunity to study the dynamics and chemistry of circumstellar disks in binary systems, especially given its unique edge-on orientation and the presence of PAHs.

References

PDS 144: THE FIRST CONFIRMED Herbig Ae–Herbig Ae WIDE BINARY

J. B. Hornbeck, C. A. Grady, M. D. Perrin, J. P. Wisniewski, B. M. Tofflemire, A. Brown, J. A. Holtzman, K. Arraki, K. Hamaguchi, B. Woodgate, R. Petre, B. Daly, N. A. Grogin, D. G. Bonfield, G. M. Williger, and J. T. Lauroesch

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0004-637X/744/1/54

Discovery of an Optically Thick, Edge-on Disk around the Herbig Ae Star PDS 144N

Perrin, Marshall D. ; Duchêne, Gaspard ; Kalas, Paul ; Graham, James R.

https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2006ApJ…645.1272P

Figure: The-position-of-PDS-144-N-top-with-respect-to-PDS-144-S-bottom-over-a-5-year

-

Dimethyl Ether Detected in MWC 480 Protoplanetary Disk

Dimethy Ether was first synthesised in 1835. It is expected to be used in biofuels in the future.

The MWC 480 protoplanetary disk is a subject of significant interest due to its complex structure and potential insights into planet formation processes.

Star Characteristics

- MWC 480 is a young Herbig Ae star located approximately 500 light-years away in the Taurus-Auriga Star-Forming Region. It is about 7 million years old and has a mass of approximately 1.7 to 2.3 times that of the Sun.

- The star has a radius of about 1.67 times that of the Sun and a luminosity of 11.2 times solar luminosity. Its surface temperature is around 8250 K.

- MWC 480 is surrounded by a protoplanetary disk that is inclined at about 37° with respect to our line of sight.

Protoplanetary Disk Features

- The disk around MWC 480 has been observed using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), revealing a ring-like structure with gap-like features that are indicative of ongoing planet formation processes.

- The disk contains complex organic molecules, including the recent detection of dimethyl ether (CH₃OCH₃), which suggests active chemical processes potentially related to the formation of life-building compounds.

O (Oxyten) in Red Color Kinematic and Chemical Properties

- The disk exhibits kinematic substructures, which are crucial for understanding the dynamics and evolution of the disk material.

- An unbiased ALMA spectral survey has been conducted to further explore the chemical composition of the disk, providing insights into the molecular environment surrounding MWC 480.

Overall, the MWC 480 protoplanetary disk serves as an important laboratory for studying the early stages of planet formation and the chemical processes that occur in young stellar environments. The presence of complex organic molecules and the disk’s structural features make it a key target for ongoing and future astronomical studies.

References

Molecules with ALMA at Planet-forming Scales (MAPS XVIII): Kinematic Substructures in the Disks of HD 163296 and MWC 480

Richard Teague, Jaehan Bae, Yuri Aikawa, Sean M. Andrews, Edwin A. Bergin, Jennifer B. Bergner, Yann Boehler, Alice S. Booth, Arthur D. Bosman, Gianni Cataldi, Ian Czekala, Viviana V. Guzmán, Jane Huang, John D. Ilee, Charles J. Law, Romane Le Gal, Feng Long, Ryan A. Loomis, François Ménard, Karin I. Öberg, Laura M. Pérez, Kamber R. Schwarz, Anibal Sierra, Catherine Walsh, David J. Wilner, Yoshihide Yamato, Ke Zhang

https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.06218

Ring structure in the MWC 480 disk revealed by ALMA★

Yao Liu, Giovanni Dipierro, Enrico Ragusa, Giuseppe Lodato, Gregory J. Herczeg, Feng Long, Daniel Harsono, Yann Boehler, Francois Menard, Doug Johnstone, Ilaria Pascucci, Paola Pinilla, Colette Salyk, Gerrit van der Plas, Sylvie Cabrit, William J. Fischer, Nathan Hendler, Carlo F. Manara, Brunella Nisini, Elisabetta Rigliaco, Henning Avenhaus1, Andrea Banzatti11 and Michael Gully-Santiago

https://www.aanda.org/articles/aa/abs/2019/02/aa34157-18/aa34157-18.html

https://arxiv.org/abs/1811.04074

An Unbiased ALMA Spectral Survey of the LkCa 15 and MWC 480 Protoplanetary Disks

Ryan A. Loomis, Karin I. Öberg, Sean M. Andrews, Edwin Bergin, Jennifer Bergner, Geoffrey A. Blake, L. Ilsedore Cleeves, Ian Czekala, Jane Huang, Romane Le Gal, Francois Ménard, Jamila Pegues, Chunhua Qi, Catherine Walsh, Jonathan P. Williams, and David J. Wilner

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/ab7cc8Catalog of Circumstellar Disks

https://www.circumstellardisks.org/show.php?id=101

-

Abundance of Water in the Form of Icy Crystals in the Frosty Leo Protoplanetary Nebula

The Frosty Leo Nebula, also known as IRAS 09371+1212, is a protoplanetary nebula located approximately 3,000 light-years from Earth in the constellation Leo. Despite their name, protoplanetary nebulae are not related to planets but are formed from material ejected by their aging central stars.

Characteristics

- Structure: The Frosty Leo Nebula features a complex structure, including a spherical halo, a disc around the central star, lobes, and large loops. This intricate shape suggests complex formation processes, possibly involving a second, unseen star.

- Composition: It is rich in water ice grains, which is unusual for such nebulae. This characteristic contributed to its nickname “Frosty Leo”.

- Symmetry and Shape: The nebula has an hourglass shape with two lobes separated by an almost edge-on dust ring. It is notable for its point reflection symmetry, a rare trait among protoplanetary nebulae.

- Molecular Envelope: The nebula’s molecular envelope is expanding at approximately 25 km/s.

Observation

- The Frosty Leo Nebula was first identified in the IRAS survey due to its cold infrared color temperatures and sharp maximum at 60 micrometers. It was named “Frosty Leo” due to its unusual infrared spectrum and the presence of crystalline ice.

- Observations have been conducted using various methods, including near-infrared imaging polarimetry in the J, H, and K′ bands.

Significance

Protoplanetary nebulae like Frosty Leo are precursors to the planetary nebula phase, where the nebula’s gas becomes illuminated by radiation from the central star. Their brief lifespans and rarity make them important subjects for astronomers studying stellar evolution.

References

Image: The frosty Leo Nebula

https://esahubble.org/images/potw1149a/

The near-infrared polarization of the pre-planetary nebula Frosty Leo

Serrano Bernal, E & Sabin, Laurence & Luna, Abraham & Rangaswamy, Devaraj & Mayya, Y. & Carrasco, Luis. (2020)

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 495. 2599-2606. 10.1093/mnras/staa1291.

-

First Time Observed Gamma-Ray Emissions from Jets of Proto-Planetary Nebula ?

Likely the first reported protoplanetary nebula IRAS 18443-0231 related to very high energy emission.

Proto-Planetary Nebula: IRAS 18443-0231

It is considered as a proto-planetary nebula, which is a transitional phase between the late stages of a star’s life and the formation of a planetary nebula.

https://twitter.com/AstroArxiv/status/1810886477481705855

Location

IRAS 18443-0231 is located almost at the center of the Fermi confidence ellipse and is related to the hard X-ray source 4XMM J184700.4-022752.

Gamma-Ray Emission

Recent studies suggest that IRAS 18443-0231 might be associated with gamma-ray emissions. This is significant because it could be the first known association between a proto-planetary nebula and gamma-ray emission.

https://twitter.com/AstroArxiv/status/1798580836264268262

Jets and Outflows

Observations have identified a compact source with jet-like morphology and an associated red-shifted CO molecular outflow. These jets are believed to be responsible for the gamma-ray emissions through mechanisms like proton-proton collisions and relativistic Bremsstrahlung.

Radio Continuum Emission

The radio continuum emission at 3 GHz shows a compact source related to faint emission with jet-like morphology. The radio spectral index values range from -0.57 to -0.39, indicating synchrotron emission due to particles accelerated by the jets.

https://twitter.com/AstroArxiv/status/1806178970884592059

This object is a subject of ongoing research, and its unique characteristics make it an intriguing target for further study in the field of astrophysics.

References:

A comprehensive analysis towards the Fermi-LAT source 4FGL J1846.9–0227: jets of a protoplanetary nebula producing γ-rays?

M E Ortega, A Petriella, S Paron

https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/532/4/4446/7710749?login=false

-

Quick Step-by-Step Guide: Installing the Latest Version of Qiskit on Windows for IBM Quantum Computing

Quantum Computing will be ideal for the research and simulation of thermodynamic systems (structural-dynamic formation processes).

NEW: IBM Qiskit Certification 2.0: https://tinyurl.com/qiskitcertification

The following quick-guide step-by-step cheat sheets videos will allow you to start and stop anytime during the installation process and avoid the starting, stopping and rewinding of how to install videos.

- Create Environment with Miniconda

Create Environment with Miniconda to keep your project tidy and manageable and avoid conflicts. 2. Activate Environment

Activate Environment in Miniconda to ensure the correct packages, dependencies, and Python version are used, providing a consistent and conflict-free setup for your projects. 3. Install PIP

Installing PIP in your environment allows you to easily manage and install Python packages specific to that environment, ensuring compatibility and avoiding conflicts. 4. Install Qiskit

Installing Qiskit allows you to develop and run quantum computing algorithms, providing access to a comprehensive set of tools for quantum programming and experimentation. 5. Install MatPlotLib

Install MatPlotLib to create high-quality, customizable visualizations in Python for data analysis and scientific research. 6. Install pylatexenc

Install pylatexenc to easily encode and format LaTeX content in Python, making it simpler to generate LaTeX documents programmatically. 7. Install ipykernel

Install ipykernel to enable Jupyter notebooks to run Python code, facilitating interactive computing and data analysis. 8. Install Jupyterlab

Install Jupyterlab for an enhanced, flexible, and interactive development environment that supports data science, scientific computing, and machine learning workflows. Check installed version Jupyter 9. Install Jupyter Notebook

Install Jupyter Notebook to create and share interactive documents that combine live code, equations, visualizations, and narrative text. Use Bloch Vector to Display State Vectors

Show Bloch Vector -

Protoplanetary Disk Latest Findings 08 2024

- Water Discovery in Protoplanetary Disks: NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has detected water vapor in the inner regions of protoplanetary disks around young stars. This discovery supports the long-held theory that icy pebbles from the outer regions drift inwards, delivering water and solids to the rocky-planet zone.

- Rich Hydrocarbon Chemistry: JWST has also observed a plethora of carbon molecules around young stars, indicating a rich hydrocarbon chemistry in protoplanetary disks. This discovery includes the first detection of ethane and other carbon-bearing molecules outside our solar system, suggesting that these disks are rich in carbon and may influence the composition of planets forming within them.

- Alignment of Stellar Jets: A striking image from JWST shows the alignment of protostellar outflows within a small region of the Serpens Nebula. This alignment is thought to be influenced by the magnetic fields within the inner disk, which launch material into twin jets perpendicular to the disk.

4. Formation of Organic Macromolecular Matter: Research suggests that the organic macromolecular matter found in meteorites could have formed in heavily irradiated zones in dust traps in planet-forming disks.

5. Viscous Circumbinary Protoplanetary Discs: Studies have shown the structure of the inner cavity in viscous circumbinary protoplanetary disks, providing insights into the formation and evolution of these systems.

6. Outflow from a Protoplanet: Observations have revealed an outflow from a protoplanet embedded in the TW Hya disk, similar to outflows from protostars. This discovery provides insights into the early stages of planet formation

-

IBEX Ribbon Study Questions

- Compare and contrast the retention theory with other leading theories explaining the IBEX Ribbon. What are the strengths and weaknesses of each theory?

- Analyze the data collected by the IBEX mission. How does the spatial distribution of the ribbon correlate with the positions of the Voyager spacecraft?

- Evaluate the impact of the IBEX Ribbon on our understanding of the heliosphere’s interaction with the interstellar medium. How does this influence current models of the heliosphere?

- Examine the role of magnetic fields in the formation of the IBEX Ribbon. How do variations in the local galactic magnetic field affect the ribbon’s characteristics?

- Investigate the methods used to detect and measure Energetic Neutral Atom (ENA) emissions. How do these methods contribute to the accuracy and reliability of the IBEX Ribbon data?

- Analyze the implications of the IBEX Ribbon findings for future space missions. What new research questions have emerged, and how might they be addressed?

- Critically assess the retention theory’s explanation of the IBEX Ribbon. What additional evidence or observations would strengthen this theory?

- Explore the potential sources of error in the IBEX mission’s data collection and analysis. How might these errors affect the interpretation of the ribbon’s properties?

- Critique the methodologies used in the IBEX mission for detecting and analyzing the Energetic Neutral Atom (ENA) emissions. What improvements could be made to enhance the accuracy and reliability of the data?

- Assess the validity of the retention theory in explaining the IBEX Ribbon. How well does this theory integrate with existing knowledge about the interstellar medium and heliosphere?

- Evaluate the impact of the IBEX Ribbon discovery on our understanding of the solar system’s boundary. How has this discovery influenced subsequent research and theoretical models?

- Analyze the strengths and limitations of the competing theories explaining the IBEX Ribbon. Which theory provides the most comprehensive explanation, and why?

- Examine the role of interdisciplinary approaches in studying the IBEX Ribbon. How do contributions from fields such as astrophysics, space science, and plasma physics enhance our understanding of this phenomenon?

- Evaluate the potential implications of the IBEX Ribbon findings for future space exploration missions. What new research directions should be prioritized based on these findings?

- Critically assess the data interpretation techniques used in the IBEX mission. How do these techniques influence the conclusions drawn about the nature and origin of the IBEX Ribbon?

- Review the theoretical models proposed to explain the IBEX Ribbon. How do these models account for the observed properties of the ribbon, and what are their predictive capabilities?

- Design a new experimental setup or mission to further investigate the IBEX Ribbon. What instruments and methodologies would you include to enhance our understanding of its properties and origins?

- Develop a comprehensive theoretical model that integrates the retention theory with other leading theories explaining the IBEX Ribbon. How would you validate this model using existing and new data?

- Propose a multi-disciplinary research project that combines astrophysics, space science, and computational modeling to study the IBEX Ribbon. What are the key objectives, methodologies, and expected outcomes of this project?

- Create a simulation framework to predict the behavior of the IBEX Ribbon under varying interstellar magnetic field conditions. What parameters would you include, and how would you test the accuracy of your simulations?

- Formulate a hypothesis about the long-term evolution of the IBEX Ribbon. What observational and theoretical evidence would you gather to support or refute your hypothesis?

- Design a collaborative international research initiative to study the IBEX Ribbon. What roles would different institutions and researchers play, and how would you coordinate the efforts to achieve the research goals?

- Develop a new analytical technique for interpreting Energetic Neutral Atom (ENA) emissions data from the IBEX mission. How would this technique improve upon existing methods, and what new insights could it provide?

- Propose a novel approach to visualize the IBEX Ribbon and its interactions with the heliosphere. What technologies and data sources would you use to create an accurate and informative visualization?

Comparison of Theories Explaining the IBEX Ribbon

1. Retention Theory

- Description: The retention theory posits that the IBEX Ribbon is formed in a special region where neutral hydrogen atoms from the solar wind cross the local galactic magnetic field. When these atoms become charged ions, they gyrate around magnetic field lines, creating waves and vibrations that trap the ions, forming the ribbon12.

- Strengths:

- Weaknesses:

2. Magnetic Mirroring Theory

- Description: This theory suggests that the ribbon is formed by the trapping of protons through magnetic mirroring effects in the local interstellar magnetic field (LISMF)3.

- Strengths:

- Weaknesses:

3. Secondary ENA Emission Theory

- Description: Proposes that the ribbon is formed by secondary emissions of Energetic Neutral Atoms (ENAs) resulting from interactions between the solar wind and interstellar medium1.

- Strengths:

- Weaknesses:

Summary

Each theory offers valuable insights into the nature of the IBEX Ribbon, with the retention theory providing a comprehensive model, the magnetic mirroring theory offering simplicity, and the secondary ENA emission theory linking directly to solar wind interactions. However, each also has its limitations, highlighting the need for further research and data to fully understand this enigmatic phenomenon.

1: SpaceNews article on IBEX’s Enigmatic Ribbon. 2: Astronomy.com article on the retention theory. 3: IOPscience article on magnetic mirroring theory.

The Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) mission has provided significant insights into the structure of the heliosphere, particularly through the discovery of the “IBEX Ribbon.” This ribbon is a narrow band of enhanced energetic neutral atom (ENA) emissions that spans across the sky and is believed to be related to the interaction between the solar wind and the local interstellar medium (LISM) 12. (Check if it is rather the ISMF – Interstellar Magnetic Field)

Spatial Distribution of the IBEX Ribbon

The IBEX Ribbon is characterized by a narrow width of about 20 degrees and an energy spectrum peaking at around 1 keV. It appears to be aligned with the local interstellar magnetic field, forming a circular arc centered on specific ecliptic coordinates 12. The ribbon’s position is relatively stable, although some variations in flux have been observed over time 1.

Positions of the Voyager Spacecraft

Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 have both crossed into interstellar space, providing valuable data on the outer boundaries of the heliosphere. As of now, Voyager 1 is approximately 164 AU from the Sun, while Voyager 2 is about 137 AU away 34. Both spacecraft are on trajectories that take them through different regions of the heliosphere and into the interstellar medium.

Correlation Analysis

The spatial distribution of the IBEX Ribbon correlates with the positions of the Voyager spacecraft in several ways:

- Alignment with Magnetic Fields: The IBEX Ribbon’s alignment with the local interstellar magnetic field suggests that the regions where Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 crossed into interstellar space are influenced by similar magnetic field structures. This alignment helps in understanding the magnetic environment encountered by the Voyagers 12.

- ENA Flux Observations: The enhanced ENA flux observed by IBEX in the ribbon region provides a complementary dataset to the in-situ measurements made by the Voyagers. This helps in constructing a more comprehensive picture of the heliosphere’s boundary and its interaction with the LISM 12.

- Spatial Retention of Ions: The ribbon’s structure is thought to result from the spatial retention of ions in the local interstellar medium, which is consistent with the observations made by the Voyagers as they moved through these regions. This retention mechanism helps explain the narrow and enhanced nature of the ribbon 12.

In summary, the data from the IBEX mission and the Voyager spacecraft together provide a detailed understanding of the heliosphere’s boundary and its interaction with the interstellar medium. The spatial distribution of the IBEX Ribbon and the positions of the Voyager spacecraft are closely linked through their shared magnetic and particle environments.

The discovery of the IBEX Ribbon by the Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) has significantly advanced our understanding of the heliosphere’s interaction with the interstellar medium (ISM). Here are some key impacts and influences on current models:

Key Impacts of the IBEX Ribbon

- Unexpected Discovery: The IBEX Ribbon was not predicted by any pre-existing models. Its discovery revealed a narrow band of energetic neutral atoms (ENAs) that is aligned perpendicular to the interstellar magnetic field1.

- Magnetic Field Insights: The Ribbon has provided crucial information about the interstellar magnetic field. It suggests that the magnetic field strength is around 3 µG and plays a significant role in shaping the heliosphere12.

- Heliosphere Structure: The Ribbon and the globally distributed flux (GDF) have helped map the structure of the heliosphere, including the thickness of the heliosheath and the deflection of the heliosphere’s tail in the direction of the interstellar magnetic field1.

- Energy Spectra: The energy spectra of the Ribbon and GDF are unique, with the Ribbon showing an excess near solar wind energies. This supports the idea that the Ribbon is produced from solar wind, although the exact mechanism remains debated1.

Influence on Current Models

- Revised Models: The discovery of the IBEX Ribbon has led to revisions in models of the heliosphere. Models now incorporate the influence of the interstellar magnetic field more prominently, affecting predictions about the shape and behavior of the heliosphere13.

- Dynamic Interactions: The Ribbon’s variability over time has shown that the heliosphere’s interaction with the ISM is dynamic, influenced by changes in solar wind speed and density3.

- Protection Mechanisms: Understanding the heliosphere’s boundaries and their interactions with the ISM helps in assessing how the heliosphere protects the solar system from cosmic radiation. This has implications for space exploration and Earth’s radiation environment1.

Overall, the IBEX Ribbon has provided a wealth of data that has reshaped our understanding of the heliosphere and its interaction with the interstellar medium, leading to more accurate and dynamic models.

-

HH 48 NE Protoplanetary Disk Ices at High Disk Altitudes

“To explain the presence of ices at high disk altitudes, we propose two possible scenarios: a disk wind that entrains sufficient amounts of dust, thus blocking part of the stellar UV radiation, or vertical mixing that cycles enough ices into the upper disk layers to balance ice photodesorption.”

HH 48 NE is a protostar located in the Chamaeleon I star-forming region, approximately 600 light-years from Earth.

It is part of a binary system with HH 48 SW, separated by a projected distance of 425 astronomical units (AU). The protoplanetary disk around HH 48 NE is of particular interest due to its nearly edge-on orientation, making it an excellent target for studying disk structure and composition.

Key characteristics of the HH 48 NE protoplanetary disk include:

Geometry:

- The disk is viewed nearly edge-on, with a lower limit inclination of 68°[1].

- It appears asymmetric in scattered light observations[1].

- A relatively large cavity (~50 AU in radius) is present, which explains the strong mid-infrared emission.

Dust properties:

- 90% of the dust mass is settled to the disk midplane, which is less than in average disks.

- The atmospheric layers contain exclusively large grains (0.3–10 µm), with small grains absent.

- There is a sharp cutoff in millimeter continuum emission.

Structure:

- The disk’s bipolar jet is tilted 6° with respect to the polar axis of the disk mid-plane.

- The gas disk appears distorted, possibly due to interaction with the companion star’s disk.

Ice composition:

- The disk is a target of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) Early Release program “Ice Age” to study its icy chemistry.

- Modeling suggests that the global abundance of main ice carriers (H2O, CO, CO2, NH3, CH4, and CH3OH) can be determined within a factor of 3, considering uncertainties in physical parameters.

- Ice features can be saturated at an optical depth of ≲1 due to local saturation.

Observational challenges:

- Spatial information for ice features at wavelengths >7 µm may be lost due to decreasing angular resolution at longer wavelengths with JWST.

- Radiative transfer effects complicate the direct relation between observed ice optical depths and column densities.

Stellar properties:

- The spectral type of the combined binary system is reported as K7, consistent with an effective temperature of 4000 K.

- Local visual extinction (Av) in the region is estimated to be ~3 mag.

Understanding the structure and composition of the HH 48 NE disk is crucial for studying ice chemistry in protoplanetary disks and serves as a stepping stone for analyzing other edge-on sources to be observed with JWST. The unique edge-on orientation allows for constraining disk properties that are difficult to determine in other orientations, making it an important target for advancing our understanding of protoplanetary disk evolution and planet formation processes.

References:

A JWST/MIRI analysis of the ice distribution and PAH emission in the protoplanetary disk HH 48 NEJ. A. Sturm, M. K. McClure, D. Harsono, J. B. Bergner, E. Dartois, A. C. A. Boogert, M. A. Cordiner, M. N. Drozdovskaya, S. Ioppolo, C. J. Law, D. C. Lis, B. A. McGuire, G. J. Melnick, J. A. Noble, K. I. Öberg, M. E. Palumbo, Y. J. Pendleton, G. Perotti, W. R. M. Rocha, R. G. Urso, E. F. van Dishoeck

https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.09627

The edge-on protoplanetary disk HH 48 NE I. Modeling the geometry and stellar parametersJ.A. Sturm, M.K. McClure, C.J. Law, D. Harsono, J.B. Bergner, E. Dartois, M.N. Drozdovskaya, S. Ioppolo, K.I. Öberg, M.E. Palumbo, Y.J. Pendleton, W.R.M. Rocha, H. Terada, R.G. Urso

https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.02338

See as well:

Issue A&AVolume 677, September 2023 Article Number A17 Number of page(s) 15 Section Interstellar and circumstellar matter DOI https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202346052 Published online 28 August 2023

The edge-on protoplanetary disk HH 48 NE II. Modeling ices and silicatesJ. A. Sturm, M. K. McClure, J. B. Bergner, D. Harsono, E. Dartois, M. N. Drozdovskaya, S. Ioppolo, K. I. Öberg, C. J. Law, M. E. Palumbo, Y. J. Pendleton, W. R. M. Rocha, H. Terada and R. G. Urso

Issue A&AVolume 677, September 2023 Article Number A18 Number of page(s) 18 Section Interstellar and circumstellar matter DOI https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202346053 Published online 28 August 2023 https://www.aanda.org/articles/aa/full_html/2023/09/aa46053-23/aa46053-23.html

-

The Watery Past of Asteroid Bennu is a Total Surprise

Is Bennu from an ocean world?

NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission has revealed significant findings from the asteroid Bennu, particularly the discovery of magnesium-sodium phosphate in the samples returned to Earth. This discovery has several implications:

Unexpected Mineral Composition:

- The presence of magnesium-sodium phosphate was surprising because it was not detected by the spacecraft’s remote sensing instruments while at Bennu.

- The phosphate found in Bennu’s samples is unusually pure and has a large grain size compared to similar findings in other meteorite samples.

Implications for Bennu’s Origin:

- The presence of phosphates suggests that Bennu might have originated from a primitive ocean world, indicating a potentially watery past for the asteroid.

- This hypothesis is supported by the detection of other water-bearing minerals like serpentine and smectite, which are typically found at mid-ocean ridges on Earth.

Astrobiological Significance:

- Phosphates are essential for Earth’s biochemistry, and their presence on Bennu raises questions about the asteroid’s past geochemical processes and its potential to harbor life-essential compounds.

- The sample also contains carbon, nitrogen, and organic compounds, which are crucial for life, providing insights into the chemical processes that could have led to the emergence of life on Earth.

Broader Scientific Impact:

- The findings underscore the importance of studying asteroids like Bennu to understand the complexities of solar system formation and prebiotic chemistry.

- The analysis of Bennu’s samples is expected to continue, with portions distributed to labs worldwide for further study, potentially yielding more intriguing discoveries about the solar system’s history and the origins of life on Earth.

Overall, the discovery of magnesium-sodium phosphate in Bennu’s samples has provided new insights into the asteroid’s history and composition, suggesting a more complex and potentially watery past than previously understood.

References:

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2024/06/240626151925.htm

https://source.wustl.edu/2024/06/surprising-phosphate-finding-in-asteroid-sample/

https://www.space.com/nasa-osiris-rex-sample-return-phosphate-ocean-world

https://www.universetoday.com/167594/asteroid-samples-were-once-part-of-a-wetter-world/