Circular Astronomy

Twitter List – See all the findings and discussions in one place

-

The Mysterious Discovery of JWST That No One Saw Coming

Are We Inside a Cosmic Whirlpool? Recent JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES) observations of mysterious cosmological anomalies in the rotational patterns of galaxies challenge our understanding of the universe and reveal surprising connections to natural growth patterns.

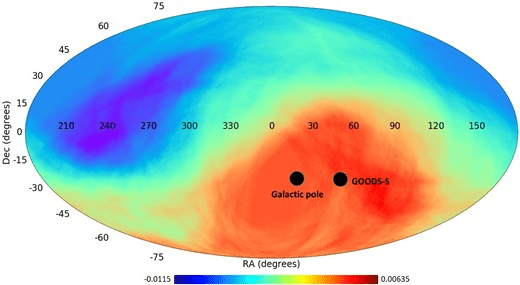

The rotation of 263 galaxies has been studied by Lior Shamir of Kansas State University, with 158 rotating clockwise and 105 rotating counterclockwise. The number of galaxies rotating in the opposite direction relative to the Milky Way is approximately 1.5 times higher than those rotating in the same direction.

New Cosmological anomalies that challenge our cosmological models and would have angered Einstein.

This observation challenges the expectation of a random distribution of galaxy rotation directions in the universe based on the isotropy assumption of the Cosmological Principle.

This is certainly not something Einstein would have liked to hear during his lifetime, but it would have excited Johannes Kepler.

What does this mean for our cosmological models, and why would it make Johannes Kepler happy?

The 1.5 ratio in galaxy rotation bias is intriguingly close to the Golden Ratio of 1.618. The Golden Ratio was one of Johannes Kepler’s two favorites. The astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) referred to the Golden Ratio as one of the “two great treasures of geometry” (the other being the Pythagorean theorem). He noted its connection to the Fibonacci sequence and its frequent appearance in nature.

What is the Fibonacci sequence?

The Italian mathematician Leonardo of Pisa, better known as Fibonacci, introduced the world to a fascinating sequence in his 1202 book Liber Abaci (The Book of Calculation). This sequence, now famously known as the Fibonacci sequence, was presented through a hypothetical problem involving the growth of a rabbit population.

The growth of a rabbit population and why it matters?

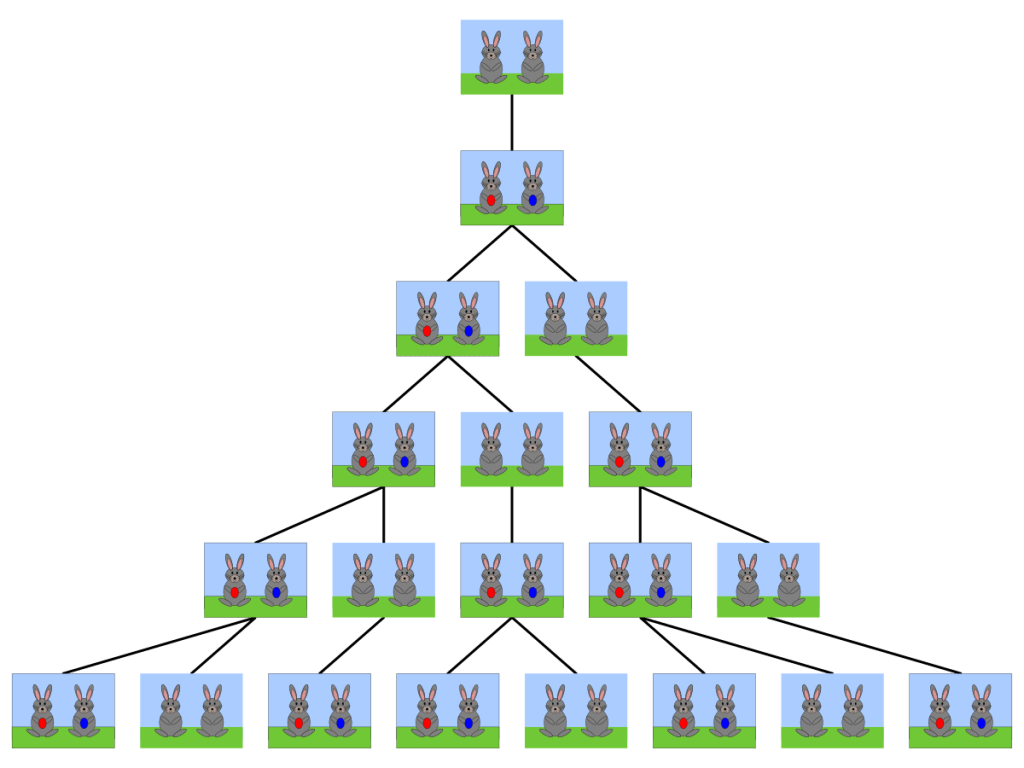

Fibonacci posed the following question: Suppose a pair of rabbits can reproduce every month starting from their second month of life. If each pair produces one new pair every month, how many pairs of rabbits will there be after a year?

The solution unfolds as follows:

- In the first month, there is 1 pair of rabbits.

- In the second month, there is still 1 pair (not yet reproducing).

- In the third month, the original pair reproduces, resulting in 2 pairs.

- In the fourth month, the original pair reproduces again, and the first offspring matures and reproduces, resulting in 3 pairs.

Image Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FibonacciRabbit.svg

This pattern continues, with each new generation adding to the total, where each term is the sum of the two preceding terms.

The Fibonacci sequence generated is: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, …

While this idealized model of a rabbit population assumes perfect conditions—no sickness, death, or other factors limiting reproduction—it reveals a growth pattern that approaches the Golden Ratio as the sequence progresses. The ratio is determined by dividing the current population by the previous population. For example, if the current population is 55 and the previous population is 34, based on the Fibonacci sequence above, the ratio of 55/34 is approximately 1.618.

However, in reality, the growth rate of a rabbit population would likely fall below this mathematical ideal ratio due to natural constraints.Yet, this growth (evolutionary) pattern appears quite often in nature, such as in the growth patterns of succulents.

The growth patterns in succulents often follow the Fibonacci sequence, as seen in the arrangement of their leaves, which spiral around the stem in a way that maximizes sunlight exposure. This spiral phyllotaxis reflects Fibonacci numbers, where the number of spirals in each direction typically corresponds to consecutive terms in the sequence.

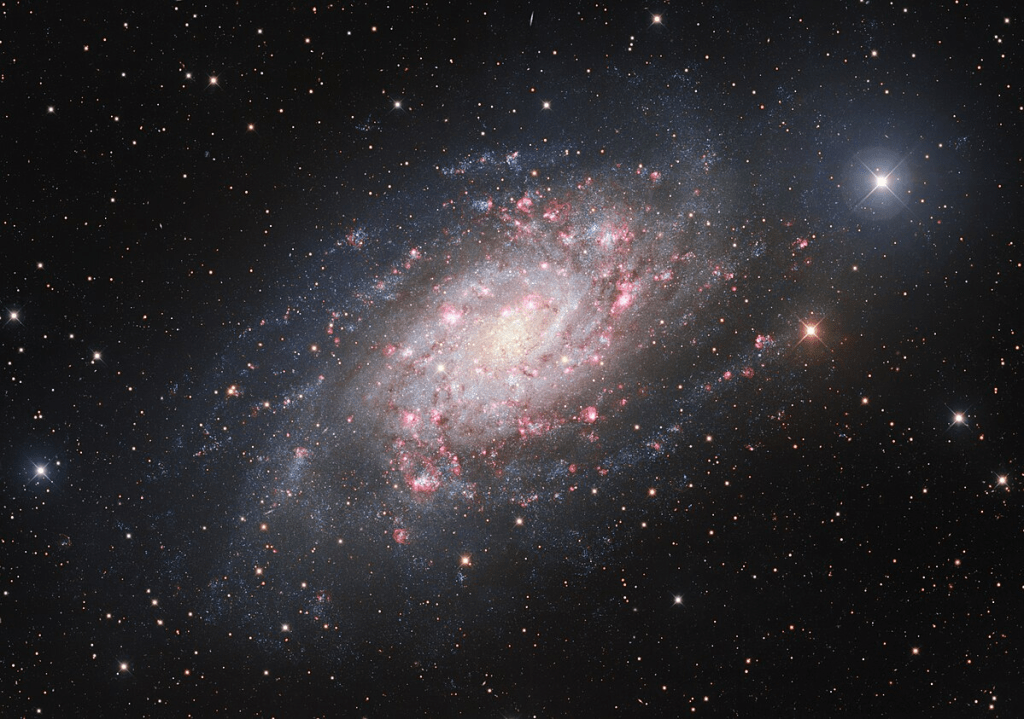

Spiral galaxies exhibit a similar growth (evolutionary) pattern in their spiral arms.

Spiral galaxies, like the Milky Way, display strikingly similar growth patterns in their spiral arms, where new stars are continuously formed and not in the center of the galaxy.

Image Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_Galaxy_of_Birth_and_Death.jpg

Returning to the observations and research conducted by Lior Shamir of Kansas State University using the JWST.

The most galaxies with clockwise rotation are the furthest away from us.

The GOODS-S field is at a part of the sky with a higher number of galaxies rotating clockwise

Image Source: Figure 10 https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staf292

“If that trend continues into the higher redshift ranges, it can also explain the higher asymmetry in the much higher redshift of the galaxies imaged by JWST. Previous observations using Earth-based telescopes e.g., Sloan Digital Sky Survey, Dark Energy Survey) and space-based telescopes (e.g., HST) also showed that the magnitude of the asymmetry increases as the redshift gets higher (Shamir 2020d).” Source: [1]“It becomes more significant at higher redshifts, suggesting a possible link to the structure of the early universe or the physics of galaxy rotation.” Source: [1]

Could the universe itself be following the same growth patterns we see in nature and spiral galaxies?

This new observation by Lior Shamir is particularly intriguing because, if we were to shift the perspective of our standard cosmological model—from one based on a singularity (the Big Bang ‘explosion’), which is currently facing a lot of challenges [2], to a growth (evolutionary) model—we would no longer be observing the early universe. Instead, we would be witnessing the formation of new galaxies in the far distance, presenting a perspective that is the complete opposite of our current worldview (paradigm).

NEW: Massive quiescent galaxy at zspec = 7.29 ± 0.01, just ∼700 Myr after the “big bang” found.

RUBIES-UDS-QG-z7 galaxy is near celestial equator.

It is considered to be a “massive quiescent galaxy’ (MQG).

These galaxies are typically characterized by the cessation of their star formation.

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/adab7a

The rotation, whether clockwise or counterclockwise, has not yet been observed.Reference

The distribution of galaxy rotation in JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey

Lior Shamir

[1 ] https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/538/1/76/8019798?login=false

The Hubble Tension in Our Own Backyard: DESI and the Nearness of the Coma Cluster

Daniel Scolnic, Adam G. Riess, Yukei S. Murakami, Erik R. Peterson, Dillon Brout, Maria Acevedo, Bastien Carreres, David O. Jones, Khaled Said, Cullan Howlett, and Gagandeep S. Anand

[2] https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2041-8213/ada0bd

Reading Recommendation:

The Golden Ratio, Mario Livio, 2002

Mario Livio was an astrophysicist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, which operates the Hubble Space Telescope.

RUBIES Reveals a Massive Quiescent Galaxy at z = 7.3

Andrea Weibel, Anna de Graaff, David J. Setton, Tim B. Miller, Pascal A. Oesch, Gabriel Brammer, Claudia D. P. Lagos, Katherine E. Whitaker, Christina C. Williams, Josephine F.W. Baggen, Rachel Bezanson, Leindert A. Boogaard, Nikko J. Cleri, Jenny E. Greene, Michaela Hirschmann, Raphael E. Hviding, Adarsh Kuruvanthodi, Ivo Labbé, Joel Leja, Michael V. Maseda, Jorryt Matthee, Ian McConachie, Rohan P. Naidu, Guido Roberts-Borsani, Daniel Schaerer, Katherine A. Suess, Francesco Valentino, Pieter van Dokkum, and Bingjie Wang (王冰洁)

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/adab7a

Appendix Spiral Galaxies:

Spiral galaxies are known for their stunning and symmetrical spiral arms, and many of them exhibit patterns that approximate logarithmic spirals, which are mathematically related to the Golden Ratio. While not all spiral galaxies perfectly follow the Golden Ratio, some exhibit spiral arm structures that closely resemble this pattern. Here are some notable examples of spiral galaxies with logarithmic spiral patterns:

1. Milky Way Galaxy

- Our own galaxy, the Milky Way, is a barred spiral galaxy with arms that approximate logarithmic spirals. The four primary spiral arms (Perseus, Sagittarius, Scutum-Centaurus, and Norma) follow a logarithmic pattern, though not perfectly aligned with the Golden Ratio.

2. M51 (Whirlpool Galaxy)

- The Whirlpool Galaxy is one of the most famous examples of a spiral galaxy with well-defined logarithmic spiral arms. Its arms are nearly symmetrical and exhibit a pattern that closely resembles the Golden Ratio.

3. M101 (Pinwheel Galaxy)

- The Pinwheel Galaxy is a grand-design spiral galaxy with prominent and well-defined spiral arms. Its structure is often cited as an example of a logarithmic spiral in astronomy.

4. NGC 1300

- NGC 1300 is a barred spiral galaxy with a striking logarithmic spiral pattern in its arms. It is often studied for its near-perfect spiral structure.

5. M74 (Phantom Galaxy)

- The Phantom Galaxy is another grand-design spiral galaxy with arms that follow a logarithmic spiral pattern. Its symmetry and structure make it a textbook example of this phenomenon.

6. NGC 1365

- Known as the Great Barred Spiral Galaxy, NGC 1365 has a prominent bar structure and spiral arms that exhibit a logarithmic pattern.

7. M81 (Bode’s Galaxy)

- Bode’s Galaxy is a spiral galaxy with arms that follow a logarithmic spiral structure. It is one of the brightest galaxies visible from Earth and a popular target for astronomers.

8. NGC 2997

- This galaxy is a grand-design spiral galaxy with arms that closely resemble logarithmic spirals. It is located in the constellation Antlia.

9. NGC 4622

- Known as the “Backward Galaxy,” NGC 4622 has a unique spiral structure with arms that follow a logarithmic pattern, though its rotation direction is unusual.

10. M33 (Triangulum Galaxy)

- The Triangulum Galaxy is a smaller spiral galaxy with arms that exhibit a logarithmic spiral structure. It is part of the Local Group, along with the Milky Way and Andromeda.

-

How to Download, View, And Edit Images from the James Webb Space Telescope with Jdaviz and Imviz

Like to comfortably view and edit images from the Jamew Webb Space Telescope like an astronomer ?

Then follow this step by step cheatsheet guides if you are using windows on a PC .

Main Software Components

There are three key software components required:

- Microsoft C++ 14

- Jupyter Notebook (Python)

- Jdaviz

Additonal

- MAST Token to be able to download the images with Imviz.

Prerequsites:

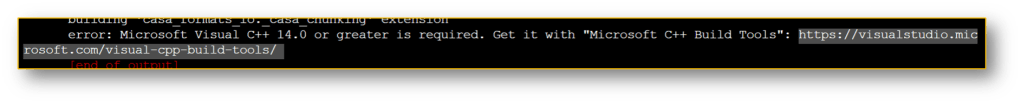

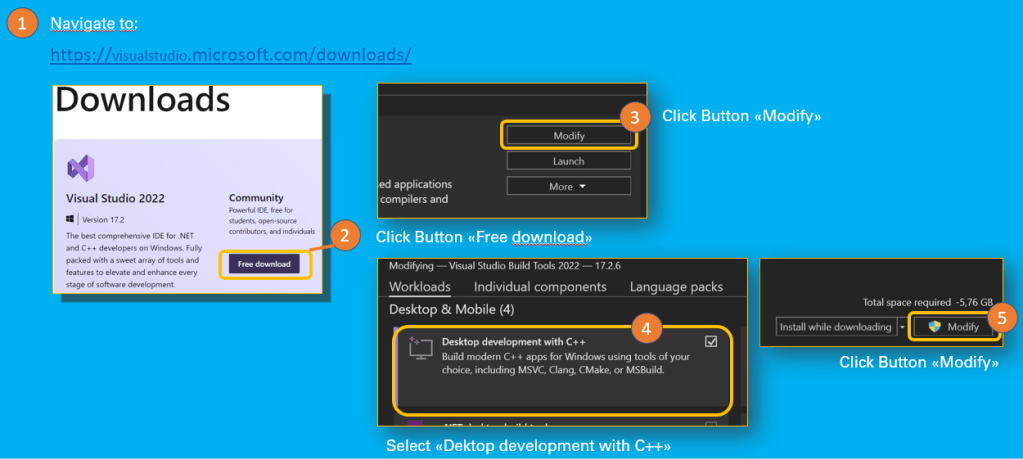

Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater

error: Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater is required If Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater is not installed, the installation of Jdaviz will fail. Without Jdaviz the downloaded images from the James Webb Space Telescope cannot be edited.

How to install Microsoft Visual C++

- Navigate to: https://visualstudio.microsoft.com/downloads/

- Download Visual Studio 2022 Community version

- Follow the instructions in this post: Install C and C++ support in Visual Studio | Microsoft Docs

Cheatsheet: Install Visual Studio 2022 MAST Token

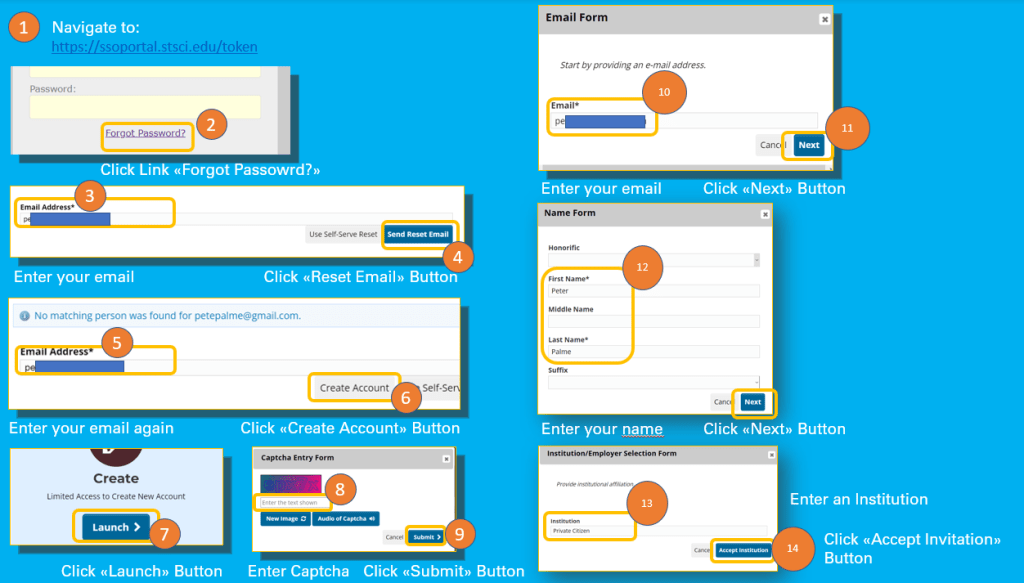

- Navigate to https://ssoportal.stsci.edu/token

If you do not have not an account yet, please follow below steps to create your account:

- Click on the Forgotten Password? link

- Enter your email Adress

- Click Send Reset Email Button

- Click Create Account Button

- Click Launch Button

- Enter the Captcha

- Click Submit Button

- Enter your email

- Click Next Button

- Fill in the Name Form

- Click Next Button

- Fill in the Insitution (e.g. Private Citizen or Citizen Scientist)

- Click Accept Institution Button

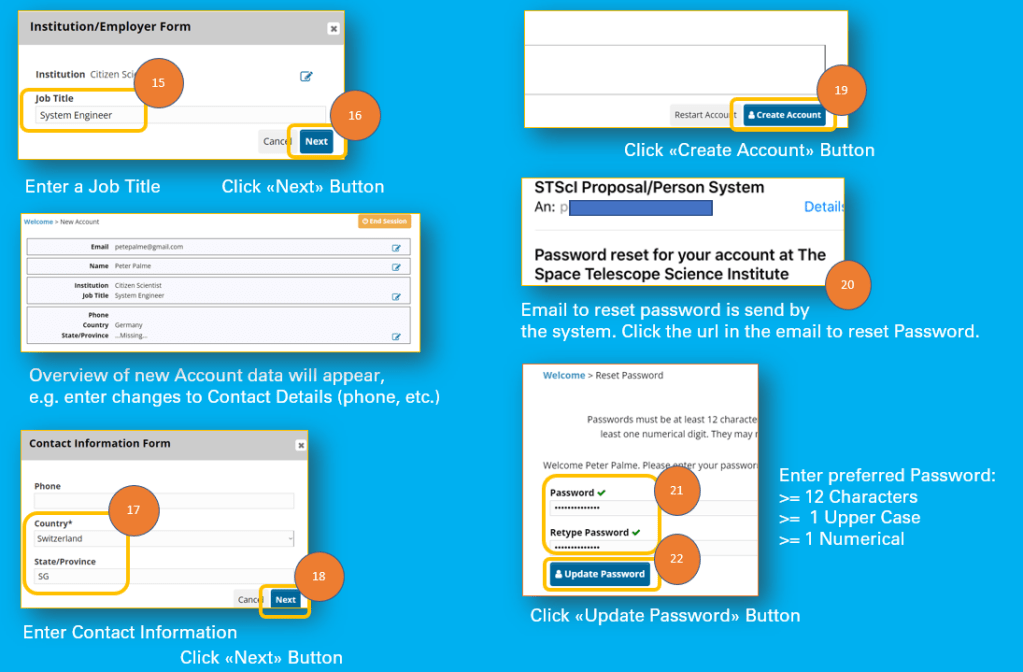

- Enter Job Title (whatever you are or like to be ;-))

- Click Next Button

- New Account Data for your review is presented, in case of missing contact data, step 17 might be necessary

- Fill in Contact Information Form

- Click Next Button

- Click Create Account Button

- In your email account open the reset password emal

- Click on the link

- Enter Password

- Enter Retype Password

- Click Update Password

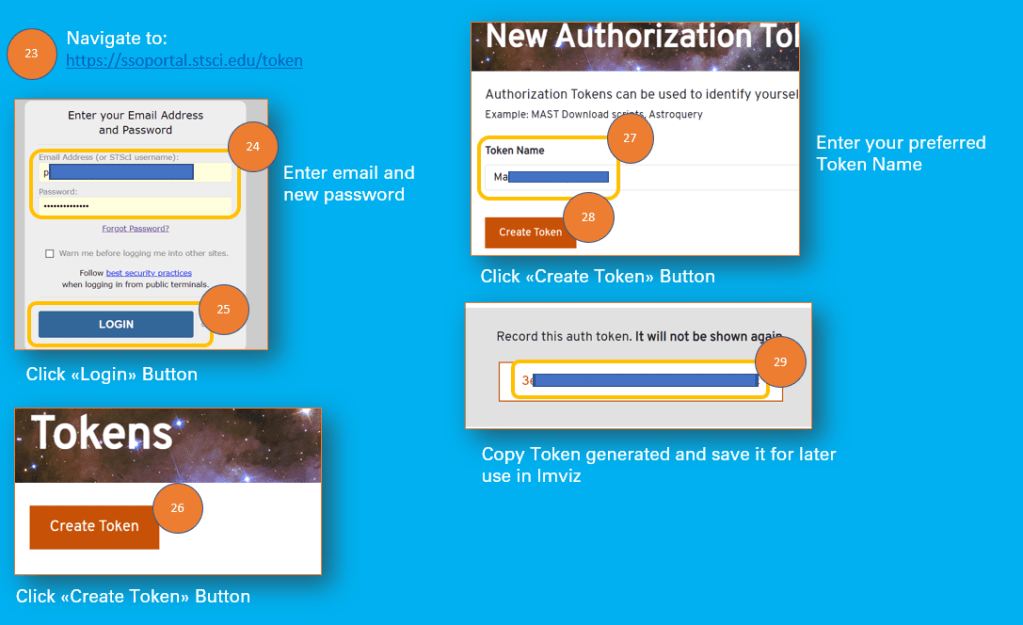

- Navigate to https://ssoportal.stsci.edu/token

- Now log on with your email and new account password

- Click Create Token Button

- Fill in a Token Name of your choice

- Click Create Token Button

- Copy the Token Number and save it for later use in Imviz to download the images from the James Webb Space Telescope

Quite a lot of steps for a Token.

Cheatsheet: Create MAST Account

Cheatsheet: Set Passord for new Account

Cheatsheet: Create MAST Token for use in Imviz Jupyter Notebook

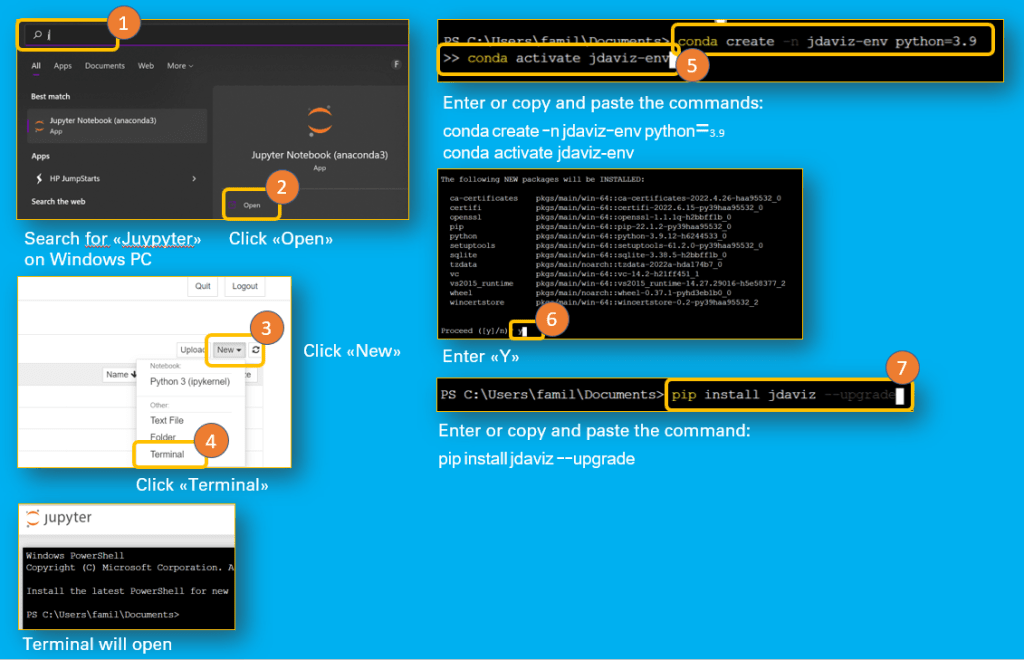

Jupyter notebook comes with the ananconda distribution.

- Navigate to: https://www.anaconda.com/products/distribution#windows

- Follow the instructions at: https://docs.anaconda.com/anaconda/install/windows/

Install Jdaviz

- Navigate to: Installation — jdaviz v2.7.2.dev6+gd24f8239

- Open the Jupyter Notebook

- Open Terminal from Jupyter Notebook

- Follow the instruction in: Installation — jdaviz v2.7.2.dev6+gd24f8239

Cheatsheet: Install Jdaviz How to use IMVIZ

Imviz is installed together with Jdaviz.

Following steps to take in order to use Imviz:

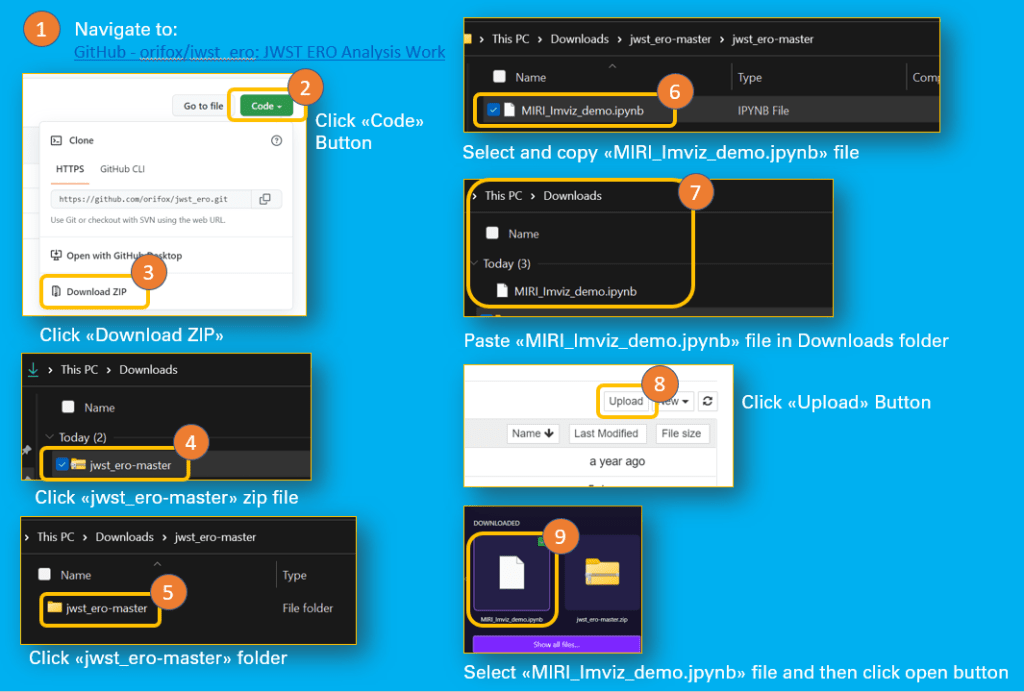

- Navigate to: GitHub – orifox/jwst_ero: JWST ERO Analysis Work

- Click Code Button

- Click Download Zip

- If you do not have unzip, then the next steps might work for you:

- In Download Folder (PC) click the jwst_ero master zip file

- Then click on the folder jwst_ero master

- Copy file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb

- Paste the file in the download folder

- Open Jupyter notebook

- Click Upload Button

- Select the file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb

- Click Open Button

- Select the file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb in the Jupyter Notebook file list

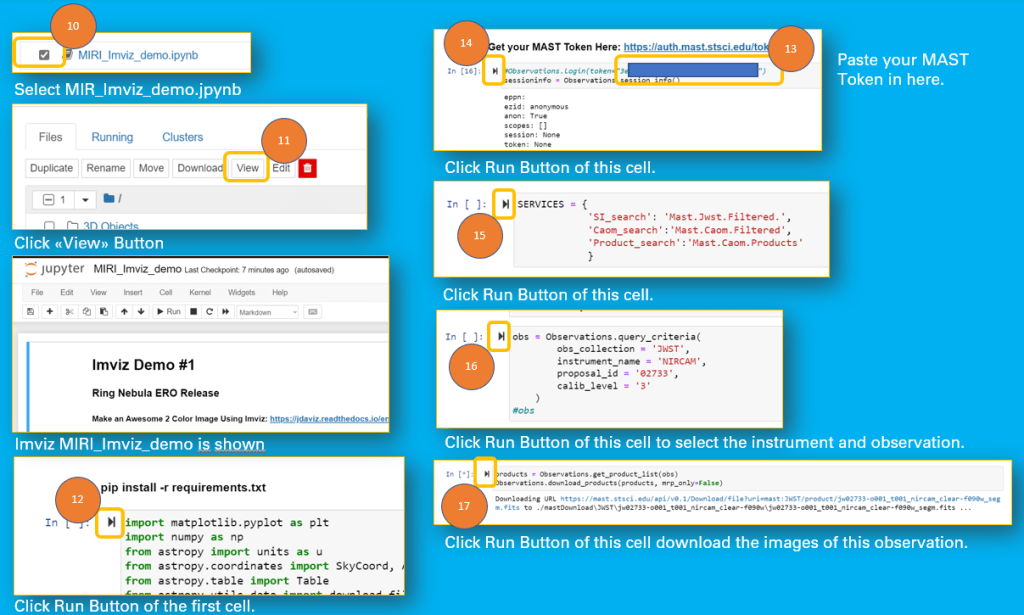

- Click View Button

- Click Run Button First Cell

- Paste MAST Token in next cell

- Click Run Button of this Cell

- Click then Run Button of next Cell

- Click Run Button of the following Cell

- Click Run Button of the next Cell to download the images

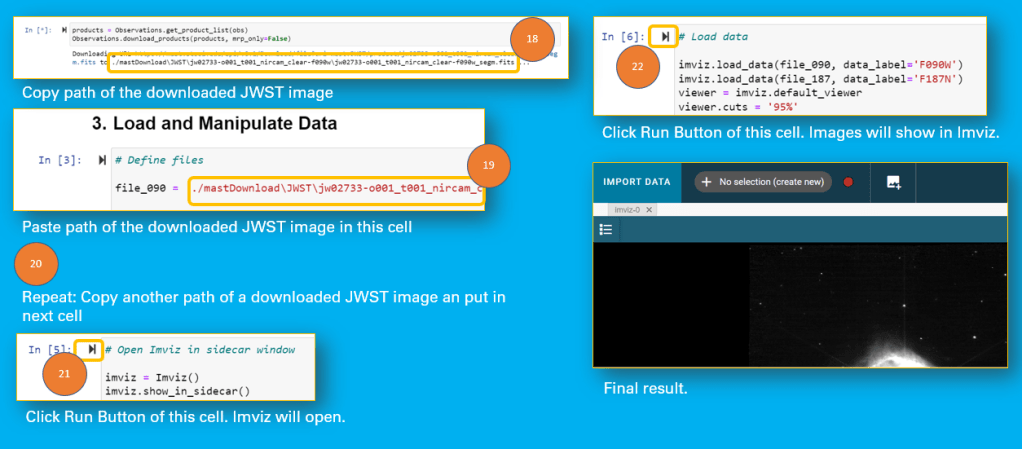

- Copy the link to the downloaded image file

- Past link into the First Cell in 3. Load and Manipulate Data

- Do the same in the next Cell

- Click Run Button of the Cell to open Imviz

- Click Run Button on the next Cell to load images in Imviz

Cheatsheet: Upload MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb in Jupyter notebook Now all set to download the images of the JWST observation:

Cheatsheet: Download JWST images with Imviz And now all is set to open and edit the images in Imviz

Cheatsheet: Open Images in Imviz And finally you are ready to follow the video tutorials in order to learn how to use Imviz to manipulate the JWST images.

Video Tutorials for Imviz:

And this is the master Ori Fox of the Imviz demo notebook file if you like to follow him on Twitter

-

Time for a new scientific debate – Accretion vs Convection

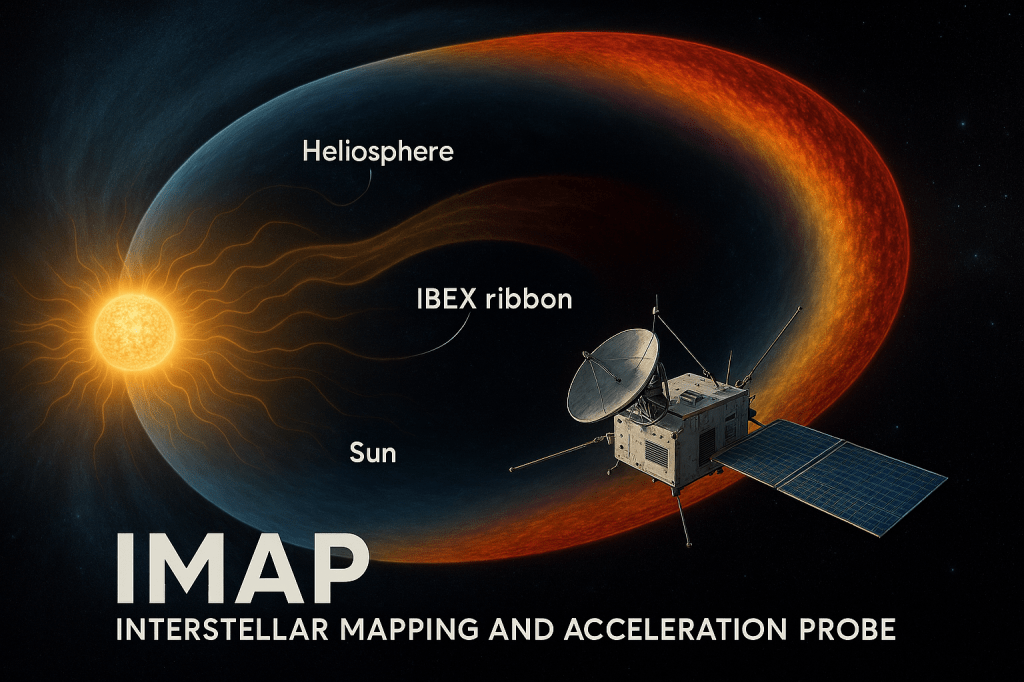

To what degree is gravity needed to form structures in space? While many believe that celestial bodies (stars, planets, moons, meteoroids) can only form through gravitational attraction in the vacuum of space, I believe that these bodies form through a thermodynamic process similar to the formation of hydrometeors (e.g., hail). This is because our solar system possesses a boundary layer, a discovery made by the Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) mission in 2013.

In simple terms: Planets, moons, and small bodies are formed within convection cells created by the jet streams of a young sun, under the influence of strong magnetic fields.

Recently, a new paper introduced quantum models in which gravity emerges from the behavior of qubits or oscillators interacting with a heat bath.

More details and link to the research paper: On the Quantum Mechanics of Entropic Forces

https://circularastronomy.com/2025/10/09/entropic-gravity-explained-how-quantum-thermodynamics-could-replace-gravitons/ -

Plasma Jets in Vacuum – Literature Review

Executive Summary: A New Frontier in Engineering and Physics

Plasma, the “fourth state of matter,” has emerged from the confines of astrophysics and fusion research to become a transformative technology at the heart of modern industry and advanced science. When harnessed in a vacuum or low-pressure environment, its unique properties offer an unparalleled degree of control and precision, enabling breakthroughs that were once confined to the pages of science fiction. This literature review, “Plasma Jets in Vacuum: A Comprehensive Review of Generation, Characterization, and Applications,” synthesizes decades of research to provide a holistic understanding of this critical field.

Our review reveals a discipline at the intersection of fundamental physics and applied engineering. From the high-stakes world of deep-space propulsion to the meticulous requirements of semiconductor manufacturing and the delicate domain of biomedical engineering, vacuum-based plasma jets are the common denominator. In space, they power the most ambitious missions, with gridded ion thrusters delivering extraordinary fuel efficiency and Hall thrusters providing a balance of thrust and longevity. On Earth, their precision enables atomic-level control over materials, allowing for the creation of next-generation microelectronics and advanced surface coatings. A particularly promising frontier lies in biomedicine, where non-thermal (cold) plasma is revolutionizing sterilization techniques and accelerating wound healing without thermal damage.

Despite these remarkable advancements, the field is not without its challenges. The literature identifies significant knowledge gaps and unresolved debates, particularly in the development of predictive computational models. The complex, coupled feedback loops that govern plasma-induced erosion in Hall thrusters, for example, have thus far resisted complete theoretical description. Furthermore, a lack of standardized, comparative studies across different plasma jet devices and operating parameters complicates the generalization and reproducibility of research findings.

The path forward for plasma science lies in a profound synergy of advanced diagnostics and high-fidelity modeling. To bridge the gap between microscopic physical processes and macroscopic device performance, the field requires multi-channel diagnostic systems with higher spatiotemporal resolution and integrated, multi-scale computational models. By addressing these foundational challenges, researchers can move from a state of empirical optimization to one of predictive design, unlocking the full potential of this versatile and powerful technology.

Biomedical Applications, Hall thruster technology, Hall Thrusters, Ion Engines, Ion thruster propulsion, Literature Review, Low-Pressure Plasma, Materials Processing, Non-Thermal Plasma, Plasma Diagnostics, Plasma Jets, Plasma Jets in Vacuum, Plasma physics, Plasma Plume, Plasma Propulsion, Reactive Species, Sterilization, Vacuum Plasma, Vacuum Plasma Jets, Vacuum Technology -

Vacuum Fluctuations and Their Impact on Quantum Computing Architectures

Executive Summary: A Structured Literature Review on Vacuum Fluctuations and Their Impact on Quantum Computing Architectures

The “empty” space of a vacuum, far from being a void, is in fact a seething sea of quantum fluctuations, a consequence of fundamental physics that challenges the very foundations of how we build quantum computers. This literature review reveals a critical, evolving narrative: the quantum vacuum’s dual role as both the primary adversary and an emerging tool for advancing quantum technologies.

The Adversary: Vacuum Fluctuations as a Source of Quantum Noise

The very fluctuations that define the quantum vacuum are a pervasive source of noise that causes qubit decoherence, a process by which fragile quantum states lose their integrity. This irreversible loss of information is the single greatest obstacle to building scalable, fault-tolerant quantum computers. The field has responded to this challenge with sophisticated mitigation strategies, including:

- Quantum Error Correction (QEC): A paradigm of redundancy that encodes fragile logical qubits into multiple physical qubits to protect against errors.

- Active Noise Suppression: A more proactive approach that uses “squeezed” vacuum states to actively reshape and reduce quantum noise. This groundbreaking technique, successfully deployed in gravitational-wave detectors to enhance their sensitivity, provides a compelling blueprint for quantum computing.

The Tool: Engineering the Quantum Vacuum for Technological Gain

A profound paradigm shift is now underway. Instead of simply mitigating the quantum vacuum, researchers are learning to actively engineer it to achieve non-intuitive control over matter. This “quantum vacuum engineering” uses optical or microwave cavities to confine and harness the vacuum’s electromagnetic fields, enabling a novel form of light-matter interaction. A recent theoretical study by Lu et al. (PNAS, 2025) provides a compelling case in point, predicting that coupling a conventional superconductor, Magnesium Diboride (

MgB2), to a vacuum electromagnetic field inside an optical cavity could increase its superconducting transition temperature by a remarkable 73%.

This breakthrough demonstrates that vacuum fluctuations can be leveraged to fundamentally alter the electronic and vibrational properties of a material. This new dimension of control holds the key to developing novel quantum materials and technologies.

The Path Forward: Gaps and Opportunities

While progress is accelerating, significant challenges remain. The long-standing “vacuum catastrophe” in theoretical physics—a massive discrepancy between the vacuum energy predicted by quantum field theory and the value measured by cosmology—underscores a fundamental gap in our understanding of the vacuum’s true nature. Resolving this theoretical chasm is a critical next step that could unlock entirely new methods for controlling the quantum realm. Future research must focus on bridging theory and experiment, specifically by developing hardware-aware QEC codes tailored to the specific nature of quantum noise and by systematically exploring new material platforms that are susceptible to vacuum engineering.

In conclusion, the quantum vacuum is a dynamic, complex, and indispensable component of the quantum world. Mastering its duality—from a source of noise to a powerful engineering tool—is essential for the future of quantum computing and materials science.

Teaching Framework for Leveraging Vacuum Fluctuations in Quantum Computing

This framework outlines a pedagogical approach for understanding and applying the principles of vacuum fluctuation engineering to optimize quantum computing architectures. It is designed to move from foundational theory to practical application, equipping practitioners with the knowledge to actively use the quantum vacuum as a resource rather than merely a source of noise.

Module 1: From Noise to Resource—The Duality of the Quantum Vacuum

- 1.1. The Nature of the Quantum Vacuum: Begin with the core concept that the quantum vacuum is not an empty void but a dynamic medium filled with fluctuating electromagnetic fields and virtual particles, a direct consequence of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle.

- 1.2. The Noise Problem: Detail how these ubiquitous vacuum fluctuations act as an environment that interacts with quantum systems, leading to decoherence and the loss of fragile quantum information. Use examples from different qubit platforms to illustrate how this noise manifests, such as vacuum-induced relaxation and dephasing in superconducting qubits.

- 1.3. The Solution Paradigm: Introduce the paradigm shift from passive mitigation to active engineering. Contrast conventional approaches like quantum error correction (QEC), which use redundancy to protect against noise, with active methods that directly manipulate the vacuum itself. Highlight the use of “squeezed vacuum states” as a proven method for reducing quantum noise, drawing on its successful application in gravitational-wave detectors.

Module 2: Practical Application—Engineering Quantum States with Cavity QED

- 2.1. Introduction to Cavity Quantum Electrodynamics (Cavity QED): Explain the core principles of cavity QED, where a quantum system is placed within an optical or microwave cavity to confine vacuum fluctuations. This confinement significantly enhances light-matter interactions, creating “vacuum-dressed” states of matter.

- 2.2. The Quantum Vacuum as an Engineering Tool: Present the vision of using this strong light-matter coupling to actively alter a material’s electronic and vibrational properties. This establishes the quantum vacuum as a new dimension in the thermodynamic phase diagram of materials, offering a powerful degree of control.

- 2.3. Case Study: Enhancing Superconductivity in MgB2: Dive into a specific, compelling example. Use the theoretical study by Lu et al. (PNAS, 2025) to demonstrate the multifaceted mechanism by which vacuum fluctuations can enhance superconductivity in a material like Magnesium Diboride ( MgB2). Explain the key steps:

- Modification of Electron Movement: The cavity’s vacuum fluctuations modify electron movement, effectively slowing them down along the cavity’s field polarization.

- Enhanced Interactions: This leads to an increased effective electron mass, which strengthens electron-phonon interactions—the mechanism that mediates superconductivity in this material.

- Frequency Reduction: The vacuum-induced charge redistribution also reduces the vibrational frequency of specific phonon modes (like the E2g mode), further reinforcing the superconducting state.

- Directional Control: Emphasize the directional nature of the effect, which depends on the cavity’s polarization and provides an additional tuning parameter for optimization.

Module 3: Methodology and Future Research

- 3.1. Modeling Vacuum-Engineered Systems: Discuss the theoretical methodologies required for this work, such as the use of advanced techniques like Quantum Electrodynamical Density-Functional Theory (QEDFT) that go beyond simplified model Hamiltonians to capture the complexity of real materials.

- 3.2. Practical Implementation and Challenges: Address the experimental hurdles of achieving the strong coupling strengths required to observe these vacuum-induced effects. Encourage future research to focus on designing new cavity geometries and materials to overcome these limitations and test theoretical predictions.

- 3.3. The Role of Noise Characterization: Integrate the importance of noise modeling and characterization in this framework. Explain how machine learning techniques can be used to infer the spectral density of an environment based on the time evolution of a system observable, providing crucial data for designing targeted mitigation and engineering strategies.

This framework provides a structured pathway for students and researchers to transition from a passive, noise-avoidance mindset to an active, engineering-focused approach, where the quantum vacuum is a central element in the design of next-generation quantum computing architectures.

-

A Critical Review and Taxonomy of Flawed Proofs for the Navier-Stokes Existence and Smoothness Problem

Executive Summary of Failed Proof Attempts

The quest to prove the global existence and smoothness of solutions to the three-dimensional incompressible Navier-Stokes equations has captivated mathematicians for over a century. Recognized as one of the seven Millennium Prize Problems by the Clay Mathematics Institute, this challenge carries a $1 million prize and represents a fundamental obstacle at the intersection of pure mathematics and fluid mechanics. This review synthesizes key findings from the vast body of literature on attempts to solve this problem, highlighting the common points of failure and the profound reasons for its enduring difficulty.

The central hurdle lies in a single, unproven premise: that for any given initial velocity, a smooth solution to the equations will exist for all time, and that this solution will never develop a “singularity,” a point of infinite velocity or pressure. While solutions are known to exist and remain smooth for a short period of time, the long-term behavior of the equations remains elusive.

Numerous, highly-publicized attempts to provide a definitive proof have failed, not due to a lack of mathematical ingenuity, but because of subtle, yet critical, flaws. The most common points of breakdown in proposed proofs include:

- Failure to Address All Scenarios: Many attempts propose a proof that works for a limited class of solutions but does not generalize to all possible initial conditions, especially those that are physically turbulent or chaotic. A valid proof must hold universally.

- Incorrect Assumptions about Function Spaces: The equations are often analyzed within specific mathematical frameworks known as Sobolev spaces or Lebesgue spaces. A recurring error has been to make an assumption about the behavior of solutions within these spaces that is not, in fact, guaranteed for the full, non-linear problem.

- The Inevitable Problem of Singularities: The core difficulty is the potential for a “blow-up” in the solution—a point in space and time where the velocity or its derivatives become infinite. While physical intuition suggests such an event is impossible, mathematicians have been unable to rigorously prove that it cannot occur. Flawed proofs often contain a subtle step that inadvertently assumes a singularity does not form, thus begging the question.

- Incomplete Treatment of Non-linear Terms: The equations’ non-linear advection term (u⋅∇u) is what makes them so powerful for describing turbulence, but also what makes them so difficult to analyze. Many failed proofs have not adequately controlled the growth of this term, allowing for the potential of uncontrolled behavior that leads to a singularity.

The consistent failure of even the most promising proof attempts underscores the immense depth of the Navier-Stokes problem. It is a testament to the complexity of turbulence and the limits of our current mathematical tools. The literature on these failures is not a catalog of defeat, but a critical roadmap that guides the ongoing research, narrowing the field of possibilities and refining the direction of future inquiry.

Deep Mathematical Hurdles in Navier-Stokes Proof Attempts

The history of failed attempts to prove the Navier-Stokes equations is a roadmap of our struggle to mathematically control the chaotic and non-linear behavior of fluids. Each failure has exposed a deep, often counter-intuitive hurdle that highlights why a simple, clever proof has yet to be found.

1. The Unruly Advection Term (u⋅∇u)

The most significant and persistent hurdle is the non-linear advection term, written as u⋅∇u

In simple terms, this term represents how a fluid’s own velocity carries its momentum. While this is what makes the equations so powerful for describing phenomena like turbulence, it is also what makes them mathematically intractable.

- The Hurdle: In linear equations, a small change in the input leads to a proportionally small change in the output. But with this non-linear term, a small, local disturbance can amplify and propagate, potentially leading to explosive, uncontrolled growth. Proving that the solution will never “blow up” requires a way to globally control this term, and every attempted proof has ultimately failed to do so for all possible initial conditions.

- The Intuition: Imagine a calm river. A small pebble creates a ripple. Now imagine that same pebble creating a whirlpool that spins faster and faster, potentially pulling in the entire river. The advection term describes this chaotic, self-reinforcing process.

2. The Elusive Nature of Singularities

The core of the Millennium Problem is proving that a solution remains “smooth” for all time. In mathematics, “smooth” means that the velocity and pressure values, as well as their derivatives (rates of change), are always finite. A “singularity,” or “blow-up,” is a theoretical point in space-time where one of these values becomes infinite.

- The Hurdle: While physical intuition dictates that infinite velocity is impossible, mathematicians have been unable to rigorously prove that a singularity cannot form. Every attempted proof that has succeeded for a short time has failed to provide a robust, long-term bound on the solution’s growth. The counter-intuitive hurdle is that we cannot prove the obvious.

- The Intuition: Think of a perfect, smooth wave on the ocean. As it approaches the shore, it gets steeper and steeper. The mathematical equations work perfectly until the moment the wave “breaks” and collapses into foam. A singularity in the Navier-Stokes equations is the mathematical equivalent of that breaking point—a point where our current tools can no longer describe what’s happening.

3. The Leaky Boxes of Function Spaces

Mathematicians analyze the equations within specific mathematical frameworks called “function spaces,” which are essentially “boxes” that contain functions with certain properties (e.g., they are smooth, they have finite energy, etc.).

- The Hurdle: Many proofs have successfully shown that a solution will remain in a specific “box” for a finite period. The deep problem is proving that the solution will not “escape” the box and enter a state of infinite energy or unbounded velocity after that time. Attempts to use “energy estimates” to put a global bound on the solution’s growth have consistently fallen short. The energy of the system is not necessarily decreasing or remaining constant, making a proof of its boundedness extremely difficult.

- The Intuition: It’s like trying to keep a bouncing ball in a room with a leaky roof. You can show that the ball stays in the room for a minute, but if there’s no way to prove the holes in the roof won’t grow bigger and let the ball escape, you can’t prove it will stay in the room forever.

In essence, the collective failures of the past are a stark reminder that we are not missing a single piece of the puzzle. We are missing an entirely new type of framework—a new way of thinking about non-linear, chaotic systems that is capable of providing the rigorous, global bounds that the Navier-Stokes equations demand.

Conflicting Assumptions in Navier-Stokes Proof Attempts

The history of failed Navier-Stokes proofs is a study in mathematical assumptions, where seemingly small choices in a proof can lead to an entire argument’s collapse. When we analyze these failures collectively, we see that many of them stem from a set of contradictory assumptions about the nature of the solution itself. The core conflict is often between assuming a certain “well-behaved” nature of the solution and the unproven, potentially singular reality of the equations.

Here, we break down some of the most prominent assumptions and their direct contradictions.

Category 1: The Assumption of “Niceness” vs. the Potential for Catastrophe

- Assumption A: A Priori Boundedness in Energy Spaces

- What it is: Many proofs assume that a solution’s energy, or a related quantity like the L2 norm of the velocity field (∫∣u∣2dx), remains bounded for all time. This is a crucial starting point because if the energy is bounded, it provides a fundamental control over the potential for a “blow-up.”

- Assumption B: The Existence of Singularities

- What it is: This is the unproven possibility that a singularity can form. A singularity is a point where the velocity or pressure becomes infinite. While no such singularity has ever been observed in a physical fluid or rigorously proven to exist in the equations, its potential presence invalidates any proof that implicitly assumes the solution remains bounded or smooth.

- Contradiction: Assumption A directly contradicts the possibility of a singularity from a mathematical standpoint. The entire goal of the Millennium Problem is to prove that Assumption B is false. Therefore, any proof that builds upon the assumption that the energy is bounded without first proving it is circular and fundamentally flawed. The conflict is existential: the proof is either valid or it’s not.

Category 2: The Assumption of Universality vs. Simplified Problem Domains

- Assumption C: Restricted Class of Initial Conditions

- What it is: Many proofs have been shown to be valid only for a specific, “tame” class of initial conditions—for instance, those with low initial energy or velocity fields that are very smooth. These are simplified scenarios that do not fully capture the complexity of the full problem.

- Assumption D: Universality of the Proof

- What it is: The Millennium Problem requires a proof that holds for all possible initial conditions, no matter how chaotic or turbulent.

- Contradiction: This is the most common contradiction found in failed proofs. A proof that is contingent on a limited set of initial conditions fails to solve the universal problem. The “solution” to a specific case is not a solution to the general problem. A great analogy is proving that a boat can cross a calm lake, but failing to prove it can cross a stormy ocean.

Category 3: The Assumption of Decaying Solutions vs. Non-Decaying Solutions

- Assumption E: The Decay of Solutions at Infinity

- What it is: In many analytical approaches, it is assumed that the solution’s velocity field approaches zero as the distance from the origin goes to infinity. This simplifies the analysis by allowing for certain boundary conditions and energy estimates.

- Assumption F: Solutions with Infinite or Slow-Decay Energy

- What it is: The full Navier-Stokes problem allows for initial conditions with infinite energy or solutions that do not decay to zero at infinity. Physically, this could represent a uniform wind field or an infinitely large vortex.

- Contradiction: Assumption E directly conflicts with Assumption F. A proof that works only for solutions with finite energy and a rapid decay at infinity fails to address the full scope of the problem as defined. It’s like trying to prove something about all numbers, but only testing it on even numbers.

In essence, the failures are not simple errors but instead expose the deep mathematical schism between what we wish to be true and the unproven reality of the equations themselves. The solution will not be found by piecing together these conflicting assumptions, but by creating a new mathematical framework that can operate without them.

Google Notebook LM – 27 Sources Navier-Stokes Failed Attempts

Assumptions in Navier-Stokes and Fluid Dynamics Research Overview

Source [47]

• The functions f, g are non-negative (f, g ≥ 0) and locally bounded.• The functions f and g satisfy f(ρ∗) = g(ρ∗) = 0.

• The function g decays as |g(ρ0)| ≤ Mρ^(-q)0 for some constants M, q > 0.

• The function f satisfies |f(ρ0)| ≤ M̃ρ^(-q)0.

• The structure of d(ρ) is as described in the Appendix of the original paper.

• The functions χ∗ and χ̃ have compact supports.

• Formulas (3.16) and (3.17) from the original paper are used.

• Test functions of Section 3 are chosen from C_c(R) (as opposed to C^2_c(R) in the original paper), which is assumed to have no consequences on the Young measure reduction.

Source [36]

• The historical overview of key developments in fluid mechanics is acknowledged as not complete.

• The density ρ is assumed to be constant throughout the thesis, implying the incompressibility condition div v = 0 for the Navier-Stokes equations.

• For previous analytical or computer-assisted existence results for Navier-Stokes equations, a certain smallness assumption on the Reynolds number is assumed to be the basis.

• For the current thesis, solutions are sought for arbitrarily large Reynolds numbers, provided the flux through a suitable intersection of the domain remains the same.

• The established computer-assisted techniques are acknowledged to “cannot cover the whole range of possible Reynolds numbers”.

• Considerations and examples are restricted to domains in R^2, while the analytical setting is noted to apply to higher dimensions with adaptions.

• The domain Ω is fixed as the infinite strip S := R × (0, 1) perturbed by a compact obstacle D ⊆ S (i.e., Ω := S \ D).

• The obstacle is chosen such that the unbounded boundary of Ω is Lipschitz.

• The obstacle D is assumed to be of two types: either D ⊆ [−d1, d1] × ([0, d2] ∪ [d3, 1]) (obstacle at the boundary) or D ⊆ [−d1, d1] × [d2, d3] (obstacle detached from the boundary), for constants d1, d2, d3 > 0 with d2 < d3 < 1.

• Computer-assisted proofs for ordinary or partial differential equations require a zero-finding formulation of the underlying problem.

• A rigorous (analytical) proof of existence requires a fixed-point argument, such as Schauder’s Fixed-point Theorem for bounded domains or Banach’s Fixed-point Theorem for unbounded domains.

• The structure assumed for the approximate solution ω̃ in (3.7) is not a restriction for most applications of computer-assisted proofs, as common methods yield a compactly supported approximate solution.

• The numerical algorithm must provide an approximation that is exactly divergence-free.

• Assumption (A1): A bound δ ≥ 0 for the defect (residual) of ω̃ has been computed, such that ‖Fω̃‖_H(Ω)′ ≤ δ.

• Assumption (A2): A constant K > 0 is available such that ‖u‖_H1_0(Ω,R2) ≤ K‖L_U+ω_u‖_H(Ω)′.

• Assumption (A3): A constant K∗ > 0 is available such that a similar inequality holds for an associated adjoint operator (implied by context of).

• For the existence and enclosure theorem, constants K and K∗ satisfying assumptions (A2) and (A3) are assumed to be already computed using computer-assisted methods.

• The linearization L_U+ω of F at ω̃ is bijective if assumptions (A2) and (A3) are satisfied (Proposition 3.3 is assumed).

• For an analytic proof, the crucial inequality (3.11) in Theorem 3.4 must be checked rigorously.

• Interval arithmetic calculations are required for computing constants δ, K, K∗ and validating inequalities, to account for rounding errors.

• Interval arithmetic ideas are applied to the set of floating-point numbers F ⊆ R instead of the entire space R to capture rounding errors.

• The IEEE 574 standard for floating-point arithmetic provides all necessary rounding modes for interval arithmetic operations.

• A concrete function V is fixed for the computation of the desired approximate solution.

• The finite element mesh, denoted by M = {Ti : i = 1, . . . , N}, consists of triangles.

• If i, j ∈ {1, . . . , N} are such that Ti ∩ Tj = {z}, then z is a corner of Ti and Tj.

• If i, j ∈ {1, . . . , N}, i ≠ j are such that Ti ∩ Tj contains more than a single point, then Ti ∩ Tj is an edge of Ti and Tj.

• Common mixed finite elements (like Raviart-Thomas or Taylor-Hood) cannot be applied because they only yield approximations that are divergence-free with respect to a finite dimensional space of test functions, not exactly divergence-free, which is not sufficient for the applications (cf. Theorem 3.4).

• For the computation of norms, interval arithmetic operations are required, especially for quadrature rules where all quadrature points and their corresponding weights must be computed rigorously.

• Conditions (5.9) and (5.10) hold true for the finite element mesh M.

• For the computation of ρ̃, the approximation ρ̃ is assumed to be in H(div,Ω,R^(2×2)), requiring finite elements that provide solutions in this space exactly.

• The success of the first approach for computing norm bounds is directly linked to the Reynolds number, and it is expected to fail if the Reynolds number is “too large”.

• For the first approach, the constant σ used in the inner product on H(Ω) is set to zero, which is possible because Poincaré’s inequality holds for the strip S and thus for the domain Ω ⊆ S.

• Former applications of computer-assisted techniques for unbounded domains strongly exploit the self-adjointness of the operator Φ^(-1)L_U+ω and use a spectral decomposition argument to compute K.

• Nakao’s method is only applicable to bounded domains, which is not the case in the authors’ considerations.

• The lack of self-adjointness is present in the current application (implied by Remark 6.1, which is not provided but referenced).

• The essential spectrum of problem (6.8) is defined via the associated self-adjoint operator (Φ^(-1)L_U+ω)∗Φ^(-1)L_U+ω.

• A positive lower bound σ > 0 for the spectral points of the eigenvalue problem (6.8) is assumed to be in hand.

• The positive eigenvalues of the eigenvalue problems (6.8) and (6.9) coincide, but it is not sufficient to consider only one problem as one might have an eigenvalue 0, so both must be considered.

• A constant K_c is assumed to have been computed using an approximate solution ω_c on a coarse finite element mesh.

• Assumptions (A1)-(A3) must be computed using the same approximate solution.

• Problem (6.12) and the base problem (6.23) are assumed to be homotopically connected, implying the existence of a family (H_t, 〈 · , · 〉_t)_t∈ of separable (complex) Hilbert spaces and a family (M_t)_t∈ of bounded, positive definite hermitian sesquilinear forms such that (H1, 〈 · , · 〉1) = (H, 〈 · , · 〉) and M1 = M.

• For all 0 ≤ s ≤ t ≤ 1, Ω(s) ⊇ Ω(t) is assumed (related to the domain deformation homotopy).

• The base problem (6.23) is assumed to be “not too far away” from problem (6.12) to be used directly as a comparison problem.

• The approximate solution ω̃ is compactly supported, i.e., ω̃ = { ω̃_0, in Ω_0; 0, in Ω \ Ω_0 } for Ω_0 ⊆ S_R ∩ Ω =: Ω_R with S_R := (−R,R) × (0, 1).

• The support of ω is contained in the bounded part Ω_R and is extended by zero on S \ Ω.

• For domain deformation homotopy, a family of domains (Ω(t))_t∈ is chosen such that Ω(0) = S and Ω(1) = Ω, and Ω(s) ⊇ Ω(t) for 0 ≤ s ≤ t ≤ 1.

• Only finitely many domains from the family (Ω(t))_t∈ are needed for the homotopy steps.

• The families (H_t, 〈 · , · 〉_t)_t∈ and (M_t)_t∈ are specifically chosen as: H_t := { u ∈ H(S) : u = 0 on S \ Ω(t) }, 〈u, ϕ〉_t := 〈u, ϕ〉_H1_0(Ω(t),R2), and M_t(u, ϕ) := (γ1 + ν)〈u, ϕ〉_H1_0(Ω(t),R2) − γ2 ∫_SR∩Ω(t) u · ϕd(x, y) for 0 ≤ t ≤ 1.

• Due to Ω(s) ⊇ Ω(t), it is assumed that H_s ⊇ H_t for all 0 ≤ s ≤ t ≤ 1, and 〈u, ϕ〉_s = 〈u, ϕ〉_t and M_s(u, u) = M_t(u, u) for all u ∈ H_t.

• The eigenvalues of interest for the base problem are located below some constant ρ_0 < σ^(0)_0 = γ1, where σ^(0)_0 is the infimum of the essential spectrum.

• Condition (6.92) is assumed to hold piecewise on each of the subintervals I1, . . . , IM and [ξ0,∞).

• On the unbounded interval I_∞ = [ξ0,∞), the functions θ_1, . . . , θ_3 are constant and thus independent of ξ.

• The constant ξ0 is greater than 0.

• The lower bounds κ and κ̂ (introduced in Section 6.2.1.4) are assumed to be in hand for computing lower bounds for the essential spectra.

• The lower bounds κ and κ̂ (satisfying (6.82) and (6.83)) are used as lower bounds for σ0 and σ̂0 respectively, for the essential spectra.

• The domain Ω still contains the obstacle D.

• The pair (ω̃, p̃) is considered as the approximate solution for the transformed Navier-Stokes equations (1.13).

• The approximation of the pressure p̃ computed with the algorithm described in Section 7.2 satisfies ∇p̃ ∈ L^2(Ω0,R2).

• An example domain with a specific geometry (presented in Figure 8.1) is used to illustrate differences between approaches for computing norm bounds K and K∗.

• A Reynolds number Re is prescribed.

• For the example domain, the parameters d_0 := 2.5, d_1 := 0.5, d_2 := 0.5 and d_3 := 1.0 are fixed.

• The choice d_3 := 1.0 is considered natural because the obstacle is located at a single side of the strip.

• For all verified computations, the corners of the corresponding triangle T must be exactly representable on the computer.

• All meshes considered have their vertices exactly representable on the computer.

• By the choice of parameters d_0, d_1, d_2, d_3, the additional assumptions on the finite element mesh M (cf. (5.9) and (5.10) in Section 5.1) required for the computation of the L_∞-norms are satisfied for the triangulation.

• The existence of reentrant corners in Ω or Ω0 is faced, and a strategy of adding already refined cells in their neighborhood is used.

• For the computation of the defect bound δ, all integrals and L_∞-norms need to be evaluated using interval arithmetic operations.

• For the first approach to norm bounds, the parameter σ (of the inner product) is set to 0.

• Theorem 3.4 was successfully applied.

• For the second approach with straightforward coefficient homotopy, σ = 1.0 is fixed for most computations.

• n0 and n̂0 denote the number of eigenvalues (below some ρ0) considered in the eigenvalue homotopy corresponding to eigenvalue problems (6.8) and (6.9) respectively.

• The essential spectra of the base problems consist of the single values γ1 (for (6.8)) and γ̂1 (for (6.9)), which provide the required lower bounds for the essential spectra.

• For the second approach with extended coefficient homotopy, all computations use the parameter σ = 0.25 for the inner product defined on H(Ω).

• The success of the eigenvalue homotopy method heavily depends on the choice of σ.

• For eigenvalue computations, a computational domain with radius twice as large as Ω0 (e.g., [−6, 6] ×) is used.

• The constant ρ0 is chosen to be relatively “small”.

• A suitable balance for the parameter σ of the inner product needs to be found, as a small σ avoids computational effort but negatively affects Lehmann-Goerisch bounds, while a large σ is suggested by examples.

• The crucial assumption needed in Corollary 6.9 is confirmed, i.e., M_t1(ũ^(t1)_N1, ũ^(t1)_N1) / 〈ũ^(t1)_N1, ũ^(t1)_N1〉_H1_0(S,R2) < ρ0.

• Assumptions (A1), (A2), and (A3) hold uniformly for all Reynolds numbers in some compact interval [Re, Re] ⊆ (0,∞).

• ω̃ ∈ H(Ω)∩W(Ω) is an approximate solution of (1.15).

• Constants δ ≥ 0, K, K∗ > 0 are computed satisfying assumptions (A1b), (A2b), and (A3b) uniformly on the compact interval [Re, Re].

• The condition 4K^2C^4/(2Re) δ < 1 holds for all Re ∈ [Re, Re].

• The first approach for computing norm bounds is used whenever possible to reduce computational effort, implying that if the second approach is used, the first one failed.

• For parallelogram obstacles, the constants d_0 := 2.5, d_1 := 0.5, d_2 := 0.5 and d_3 := 1.0 are fixed.

• Each finite element mesh considered consists of triangles with corners exactly representable on the computer, which is possible due to 45° angles and exact representability of obstacle corners.

• For Navier-Stokes equations, the linearized operator is not self-adjoint.

• Computer-assisted methods with the second approach and the extended homotopy method theoretically allow proving the existence of a solution for arbitrarily high Reynolds numbers, provided it exists and enough computational power is available.

• For future projects, considering the base problem on the space H(S) instead of H1_0 is a possibility.

• The methods presented apply to the 3-dimensional case, and Theorem 3.4 remains valid for 3D.

• For the 3D case, adaptions are necessary at several stages, such as the definition of function V and the type of divergence-free finite elements (Argyris elements are not applicable).

• Exact quadrature points and weights are required to compute integrals rigorously.

• For the setup of the transformation Φ_T, the corners of the corresponding cell need to be known rigorously.

• Functionals L̂_1, . . . , L̂_21 : P_5(T̂) → R represent the degrees of freedom for the reference triangle T̂.

• The reference shape functions ζ̂_1, . . . , ζ̂_21 ∈ P_5(T̂) have been computed to satisfy L̂_i(ζ̂_j) = δ_i,j.

• The implementation of higher-order Raviart Thomas elements uses ideas described by Ervin in [25, Section 3.4].

• For Raviart Thomas elements, a reference triangle T̂ and a counterclockwise numbering of edges starting at zero are considered.

• H denotes a separable (complex) Hilbert space endowed with the inner product N, and M is a bounded, positive definite symmetric bilinear form on H.

• All eigenvalues of the considered eigenvalue problem are well separated (i.e., no clustered eigenvalues exist).

• Results for estimating integral terms, proved for functions in H1_0(Ω,R2), remain valid if H1_0(Ω,R2) is replaced by H(Ω), as H(Ω) ⊆ H1_0(Ω,R2).

• For Lemma A.9, u, v, ϕ ∈ H1_0(Ω,R2).

• For calculating Argyris reference shape functions, an ansatz ζ̂_j(x̂, ŷ) = ∑_(k=0)^5 ∑_(l=0)^k w^(j)_k,l x̂^lŷ^(k-l) is used.

• For Lemma A.14, k ∈ N.

Source [48]

• u, v ∈ H1_0(Ω) with ∇ · u = 0.

• Ω is a smooth bounded domain in R^2.

• The inequalities ‖u · ∇v‖_L2 ≤ C‖∇u‖_L2‖∇v‖_L2 and ‖u · ∇v‖_L2 ≤ C‖u‖_L2‖v‖_H2 are stated as erroneous in the original paper, invalidating the proof of Proposition 1.

Source[26]:

• The initial vorticity ω0 is bounded.

• A suitable decay of ω0 at infinity is required, e.g., ω0 in L2, noting it’s a ‘soft assumption’ without quantitative dependence on ‖ω0‖_2.

• Estimates are performed on a sequence of smooth (entire in the spatial variable) global-in-time approximations.

• r ∈ (0, 1].

• f is a bounded, continuous vector-valued function on R^3.

• For any pair (λ, δ), λ ∈ (0, 1) and δ ∈ (1/(1+λ), 1), there exists a constant c∗(λ, δ) > 0 such that if ‖f‖_H-1 ≤ c∗(λ, δ) r^(5/2) ‖f‖_∞ then each of the six super-level sets S_i,±λ is r-semi-mixed with the ratio δ.

Source [41]:

• A constant ρ∗ > 0 exists for the pressure law.

• Solutions are allowed to admit non-trivial end states (ρ±, u±) such that lim_(x→±∞)(ρ, u) = (ρ±, u±).

• Smooth, monotone functions (ρ̄(x), ū(x)) are chosen such that, for some L0 > 1, (ρ̄(x), ū(x)) = (ρ+, u+) for x ≥ L0 and (ρ−, u−) for x ≤ −L0.

• These reference functions are fixed at the very start of the approach and do not change later.

• Pressure laws have linear growth at high densities.

• Pressure functions satisfy condition (1.7).

• The entropy kernel χ = χ(ρ, u, s) is a fundamental solution of the entropy equation (1.11).

• The distribution ψ is of specific types: ψ ∈ {δ(u−s±k(1)), H(u−s±k(1)), PV(u−s±k(1)), Ci(u−s±k(1))}.

• Initial data (ρε_0, uε_0) are given.

• Estimates are independent of ε ∈ (0, ε0] for some fixed ε0 > 0.

• Initial data must be of finite-energy: sup_ε E[ρε_0, uε_0] ≤ E0 < ∞.

• Initial density must satisfy a weighted derivative bound: sup_ε ε^2 ∫_R |ρε_0,x(x)|^2 / ρε_0(x)^3 dx ≤ E1 < ∞.

• Relative total initial momentum should be finite: sup_ε ∫_R ρε_0(x)|uε_0(x)−ū(x)| dx ≤ M0 < ∞.

• An additional condition is ρε_0 ≥ cε_0 > 0.

• These initial conditions can be guaranteed by cutting off the initial data by max{ρ0, ε^(1/2)} and then mollifying at a suitable scale.

• ψ ∈ C^2_c(R).

• ψ1, ψ2 ∈ C^2_c(R) are test functions.

• s1, s2, s3 ∈ R.

• The support of ν is contained in V ∪ ⋃_k (ρk, uk), where (ρk, uk) are such that if (ρk, uk) ∈ suppχ(s), then (ρk′, uk′) ∉ suppχ(s) for all k′ ≠ k.

• s1 and s2 are chosen such that (ρk, uk) ∈ suppχ(s1)χ(s2).

• (T2, T3) corresponds to one of the pairs: (δ, δ), (PV,PV), (Q2, Q3), (δ,PV), (PV, Q3), (δ,Q3), where Q2, Q3 ∈ {H,Ci, R}.

• Mollifying kernels φ2, φ3 ∈ C^∞_c(−1, 1) are chosen such that ∫_R φj(sj) dsj = 1 and φj ≥ 0 for j = 2, 3.

Source [33]:

• A singularity at finite time t∗ requires that ∫_t max|ω|dt must diverge as t→t∗.

• For the Euler equations, the direction of the vorticity must be indeterminate in the limit as the singularity is approached.

Source [44]:

• The hypotheses (1.5)-(1.8) hold.

• (ρ0,u0) are given functions satisfying (1.9)-(1.10).

• (ρ,u) and (ρ̃, ũ) are smooth local-in-time solutions to the systems (NSENC) and (NSEDC) respectively, defined on Ω× [0, T ] with the same initial data (ρ0,u0), as described by Theorem 1.1.

• M0 is fixed as in the statement of Theorem 1.1.

• (ρ̃, ũ) and (ρ,u) are smooth classical solutions to system (1.1) defined on Ω × [0, T ] with boundary conditions (1.3) and (1.4) respectively, satisfying bounds (1.11)-(1.12).

• (ρ̃, ũ) and (ρ,u) have the same initial data (ρ0,u0) which satisfy (1.9)-(1.10).

From “2016_7_De_Rosa.pdf”:

• The exponent α is suitably small (below 1/2).

• The work is in a (spatial) periodic setting: T^3 = S^1×S^1×S^1, identified with the cube [0,2π]^3 in R^3.

• α < 1/2 and 1/2 ≤ e ≤ 1.

• If c > max( (3−2α)/(2(1−2α)), ‖e‖^(1−2α)/(b(2α+γ−1))1, ‖e‖^(1−2α)/(2−2α)2, ‖e‖^1 ), then there exists a sequence of triples (vq, pq, R̊q).

• α ∈ [1/4, 1/2) and b > 1.

• µ, λ_q+1 ≥ 1 and ` ≤ 1.

• The condition δ^(1/2)_q λ_q ≤ µ is satisfied (CFL condition).

• For comparing energy profiles, e(0) = ẽ(0) and e′(0) = ẽ′(0).

• The choice of parameters η,M,a,b,c (from Chapter 2) works for both energy profiles.

From “2112.03116v1.pdf”:

• a0 ∈ C^∞(R^3 \ {0}) is divergence free and scaling invariant, and σ ∈ R is a size parameter.

• For |σ| ≪ 1, existence and uniqueness fall into the known perturbation theory of Koch and Tataru in BMO^(−1).

From “2405.19249v1.pdf”:

• Previous results on nonlinear inviscid damping depend heavily on Fourier analysis methods, which assume the perturbation vorticity remains compactly supported away from the boundary. The current work aims to also use physical space methods.

• A change-of-coordinates (x, y) 7→ (z, v) is defined to eliminate the background (time-varying) shear flow and propagate regularity.

• The validity of prior techniques from for controlling interior vorticity and interior coordinate system norms is assumed.

• ω_in satisfies the hypotheses of Theorem 1.1.

• The case ν = 0 is covered by.

• Regularity is measured in the coordinate system defined by ω0.

• Two essential Gevrey indices are defined: 1/2 < r < 1 (Interior Gevrey 1/r Index) and 1 < s (Exterior Pseudo-Gevrey s Index).

• r > 1/2 is chosen close to 1/2 for technical convenience.

• λ0 is chosen small for technical convenience.

• ǫ is sufficiently small.

• Bootstrap hypotheses are assumed.

• t . ν^(−1/3−1/ζ) for 0 < ζ < 1/78.

• The constants {θn} appearing in (2.55) – (2.69) are chosen as in.

• The bootstrap hypotheses (2.117),(2.118),(2.119), and (2.120) hold on [0, T] (for Theorem 2.13 in).

• ν ≪ 1.

• ǫ is sufficiently small (for Lemma 3.8).

• Functions f, g are sufficiently regular for product rules.

• Uniform bounds for t, η, ν and k ≠ 0 hold.

• f_m,n is a sequence of functions related by f_m,n := ∂_x^m Γ_n f.

• G_m,n is a sequence of weight functions.

• The cut-off functions satisfy χ_m’+n’ = 1 on the support of χ’_m’+n’+1.

• Specific conditions m ≥ 4N and n ≥ 4N are assumed for a particular case in the proof.

• Inner products are defined as in (5.1).

• Inner products are defined as in (5.24).

• H,G,H are the solutions of equations (2.7), (2.6), and (2.8) respectively.

• Relations (2.138) and (2.139) hold true.

• Remark 6.1, Hölder’s inequality, and the bootstrap assumptions are used.

• n ≥ 1.

• Relation (2.141) holds.

• j = 1, 3 for Lemma 8.2.

• U ∈ L_∞ (for estimating Err^(4)_LHS).

• A priori estimates available from are used to provide uniform estimates over νt^(3+δ) ≤ 1.

From “2410.09261v5.pdf”:

• The main result is the construction of non-smooth entropy production maximizing solutions of the Navier-Stokes equation of the Leray-Hopf (LH) class of weak solutions.

• The criteria of are necessary for blowup.

• Numerical study provides strong evidence for the existence of non-smooth solutions.

• The Foias description of Navier-Stokes turbulence as an LH weak solution provides the constructive step.

• The existence of entropy production maximizing solutions of the Navier-Stokes equation is established in.

• The theory of vector and tensor spherical harmonics is used.

• The Lagrangian for space time smooth fluids, derived from, influenced the authors’ thinking.

• Scaling analysis, based on the renormalization group, also influenced the authors’ thinking.

• The Hilbert space for this theory is the space H of L^2 incompressible vector fields defined on the periodic cube T^3.

• The initial data in H is continuous.

• A one-dimensional space of singular solutions is eliminated.

• After a global Galilean uniform drift transformation, u and f can always be assumed to have a zero spatial average.

• The viscous dissipation term is necessarily SRI (specific to the context) due to restrictions on its possible forms.

• The complexified bilinear form B is written as B(u, v)_C.

• The proof of analyticity for NSRI moments of order one is based on the energy conservation of Lemma III.2, with an entropy principle hypothesis and non-negativity of the turbulent dissipation rates.

• The numerical program of documents a rapid near total blowup in enstrophy, followed by a slower blowup in the energy.

• Within the energy spherical harmonics, restricting the statistics to the single 3D mode ℓ = 2 is sufficient.

From “ADA034123.pdf”:

• The v. Neumann stability analysis for the local linearized model will most likely impose restrictions on Δt and Δx for stable computation, which should be observed by all approximate solutions.

• A vector unknown function IJ(t, x) of dimension p is to be calculated.

• The matrix B is chosen to be the main tridiagonal elements of A.

• All artificial sources and doublets etc. are assumed to properly vanish in the steady state limit.

• The choice of B is dictated by the desire to reduce computational effort in obtaining the steady solution, irrespective of its physical correspondence to some temporal flow field.

• Without external artificial sources, nature has demonstrated that a steady state will eventually be reached.

• The suitable choice of acceleration parameters, specific to the problem type and class of prescribed boundary data, is required for reducing computational effort in steady flow problems.

• Distributed dipoles arising from truncation errors of every computational cell must be suppressed or eliminated, which can be achieved through careful formulation.

• A suitable property is implicit in the mathematical abstraction of continuity and differentiability of the functions in question.

• The differential formulations in terms of different dependent and independent variables are all equivalent, but this is not necessarily the case for difference approximations of conservation laws.

• Universal functions of the genuine solution u(x) vanish on both boundaries and have their absolute magnitudes less than 0.1.

• Truncation errors ET are expected to be of the order of (Re Δx)^2/10 for second-order accurate schemes.

• For Re Δx ~ O(1) and finite values of α ~ O(1), the estimate of the maximum absolute truncation errors is valid.

• The decay characteristics described by the universal function B_k may be used where the one-dimensional model is appropriate.

• The steady state criterion |U_~I| < O(Δx)^n is sufficiently accurate in an n-th order accurate scheme.

• The truncation error is expected to be *~ (Re Δx)^n* for conservative difference formulation of n-th order formal accuracy.

• Influence functions B1, 2, . . . are not likely to possess maximum magnitudes much less than 10^(−1).

• For r and s > 0 and < 1, specific (ill-rendered) inequalities relating r and s are stated.

• Spurious solutions will be suppressed as long as the same boundary values of U’_~1 are used at every step.

• These boundary values can be determined by the approximate boundary conditions B(T) U_~ – 0, and may contain errors.

• The maximum permissible change of U per mesh (ΔU)_max is one half the |u_1-u_2| across the discontinuity, to avoid shock-induced large oscillations.

• Within the linearized framework, criterion (5.32) (from) should be equally applicable.

• Most solutions of Poisson-type equations in the literature cannot be analyzed for an error estimate primarily because of the non-conservative form of the difference formulation.

• Experimental data are generally not available to provide a quantitative estimate of the error of computed results.

• For numerical integrations by Jenson and Hamielec et al., uniform outflow was approximated as a downstream boundary condition.

• They ensured that steady state results were essentially independent of further mesh reduction from mesh sizes Δx = 1/20.

From “IJNMF.final.2004.pdf”:

• Exact solutions are used to accurately evaluate the discretization error in the numerical solutions.

• Modeling and Simulation (M&S) is viewed as the numerical solution to any set of partial differential equations that govern continuum mechanics or energy transport.

• The engineering community must gain increased confidence for M&S to fully achieve its potential.

• Sources of error in M&S are categorized into physical modeling errors (validation-related) and mathematical errors (verification-related).

• In the method of manufactured solutions, an analytical solution is chosen a priori and the governing equations are modified by the addition of analytical source terms.

• Manufactured solutions are chosen to be sufficiently general so as to exercise all terms in the governing equations.

• Adherence to guidelines ensures that the formal order of accuracy is attainable on reasonably coarse meshes.

• The domain examined is 0 ≤ x/L ≤ 1 and 0 ≤ y/L ≤ 1 with L = 1 m.

• Only uniform Cartesian meshes are examined, so the codes cannot be said to be verified for arbitrary meshes.

• For the Euler Equations, the general form of the primitive solution variables is chosen as a function of sines and cosines.

• In this case (Euler), φ_x, φ_y, φ_xy are constants (subscripts not denoting differentiation).

• The chosen solutions are smoothly varying functions in space.

• Temporal accuracy is not addressed in this study.

• The governing equations were applied to the chosen solutions using Mathematica™ symbolic manipulation software to generate FORTRAN code for the resulting source terms.

• For a given control volume, the source terms were simply evaluated using the values at the control-volume centroid.

• For the Navier-Stokes case, the flow is assumed to be subsonic over the entire domain.

• The absolute viscosity µ = 10 N·s/m^2 is chosen to ensure that the viscous terms are of the same order of magnitude as the convective terms, minimizing the possibility of a “false positive” on the order of accuracy test.

• The solutions and source terms are smooth, with variations in both the x and y directions.

• The boundary requires the specification of one property and the extrapolation of two properties from within the domain.

• Applying a large viscosity value for the manufactured solution makes the use of an inviscid boundary condition questionable, but the order of accuracy of the interior points was not affected.

• Further investigation of appropriate boundary conditions for this case is beyond the scope of this paper.

• Options not verified in the current study include: solver efficiency and stability (not verifiable with the method), nonuniform or curvilinear meshes, temporal accuracy (manufactured solutions not functions of time), and variable transport properties µ and k.

From “JGomezSerrano.pdf”:

• The dissertation has two parts: classical analysis/PDE techniques, and computer-assisted proofs.

• Initial conditions are a graph.

• A turning singularity develops in finite time.

• The interface stops being a graph when a turning singularity develops.

• The interface finally collapses into a splash singularity.

• The first part of the result (turning singularity) was proved by Castro et al..

• The connection between the turning singularity and splash singularity results is not evident a priori, as it’s not known if the solution sets have common elements.

• The completion of the proof (connecting turning to splash) is based on techniques where the computer predominates as a rigorous theorem prover tool.

• Castro et al. proved that a class of initial data develops turning singularities for the Muskat problem, moving into the unstable regime.

• The study compares different Muskat models: confined (fluids between fixed boundaries) and non-confined, and cases with permeability jumps (inhomogeneous model).

• No claim is made that splash and splat are the only singularities that can arise.

• Elementary potential theory is assumed for irrotational divergence-free vector fields v(x, y, t) defined on a region Ω(t) ⊂ R^2 with a smooth periodic boundary.

• v is smooth up to the boundary and 2π-periodic with respect to horizontal translations.

• v has finite energy.

• The function c(α, t) can be picked arbitrarily, as it only influences the parametrization of ∂Ω(t).

• z ∈ H^k(T), ϕ ∈ H^(k-1/2)(T) and ω ∈ H^(k-2)(T) as part of the energy estimates.

• Techniques from [28, Section 6.4] are applicable for treating singular terms.

• k ≥ 3 for Lemma 2.4.6.

• k = 4 for the proof of a specific lemma; other cases are left to the reader.

• k ≥ 4 for Lemma 2.4.15.

• zε,δ,µ(α, t) ∈ H^4(T), ωε,δ,µ(α, t) ∈ H^2(T), ϕε,δ,µ(α, t) ∈ H^3(T).

• It is required that ∂_tϕε,δ ∈ H^3(T) (instead of H^(3+1/2)(T)) for specific energy estimates.

• The function ϕ̃(α, t) = Q^2(α, t)ω̃(α, t) / (2|z̃α(α, t)|) − c̃(α, t)|z̃α(α, t)| (introduced by Beale et al. and Ambrose-Masmoudi) will be used to prove local existence in Sobolev spaces.

• A commutator estimate for convolutions is repeatedly used.

• NICE3B implies ∫ Q^j∂_α^k(K̃)∂_α^k(NICE3B) ≤ CE_p^k(t) for some positive constants C, p and any j.

• N stands for the maximum number of derivatives of the function to be evaluated.

• The coefficients (f)_k are the coefficients of the Taylor series around x0 up to order N.

• t ∈ [t0, t1] is a small time interval.

• A,B,E depend in a reasonable way on t.

• An upper bound for ‖S^(−1)_t‖ is obtained, assuming ‖S^(−1)_t0‖ ≤ C0.

• The classical method of adding and subtracting the same term is used to create differences and eliminate occurrences of variables (z, ω, ϕ).

• The computation and bounding of the Birkhoff-Rott operator is the most expensive.

• The expansion (Q^2(z)−Q^2(x)) = 1/8 〈 (1+x^4)/x, (3x^2−1)/x^2 〉 D +O(D^2) is used.

• The same methods as before can be applied to the equations with f = g = 0, which are satisfied by (z, ω, ϕ).

• The evolution of a fluid in a porous medium is an interesting problem in fluid mechanics.

• Darcy’s law applies, with the permeability of the medium κ equal to b^2/12.

• The work is conducted in the two-dimensional case, with generalization to 3D being immediate.

• In subsequent sections, the inhomogeneous, non-confined regime for the Muskat problem will be investigated.

• The C-XSC library will be used for rigorous computations.

• Having a confined medium plays a role in the mechanism for achieving turning singularities.

• There are cases where the jump in permeabilities can either prevent or promote singularities, or have no impact.

• Theorems 6.2.2 and 6.2.3 are more general than [16, Theorem 3, Theorem 4] because they suppress any smallness assumption in |K| or largeness in h2.

• The analytical part of the theorems is detailed in and.

• Specific curves z1(α) and z2(α) are defined for α ∈ [−π, π] and extended periodically in the horizontal variable.

• Specific parameters (N = 8192, RelTol = 10^(−5), AbsTol = 10^(−5), K = 1, h2 = π^2) are used for running the program.

• There is turning for all −1 < K < K1 and no turning for all K2 < K < 1 for a short enough time.

From “Lee,Michael.pdf”:

• The torus is chosen for simplicity because it is compact and has no boundary.

• A divergence-free initial condition v0 is given.

• The flow is of an incompressible homogeneous fluid.

• There is a body force field f.

• The Navier-Stokes equations describe the flow.

• 1 ≤ p, q, r < ∞.

• Ω is a measurable set in R^n.

• u belongs to L^p(Ω) ∩ L^q(Ω).

• ‖aj‖_L2 = 1.

• Uniform bounds C1, C2 are obtained via other assumptions.

From “Michele-Thesis.pdf”:

• The method used to tackle the problem is Convex Integration.

• The main result of the thesis concerns the fractional Navier-Stokes equations with a Laplacian exponent θ < 1/3.

• The general strategy of the proof involves defining suitable relaxations of the notion of solution (“subsolutions”) and approximating one kind of subsolution with another that is closer to the notion of solution.

• Adapted subsolutions (with R̊(·,0) ≡ 0 and C1 norm of velocity blowing up at a controlled rate at t=0) are the basis for a quantitative criterion for non-uniqueness.

• Equations are termed hypodissipative when θ < 1 and hyperdissipative when θ > 1.

• Solutions for θ < 1/3 are studied unless otherwise stated.

• The equations model the behavior of a fluid with internal friction interaction when θ ∈ [1/2,1].

• Classical solutions of the Euler, Navier-Stokes, and fractional Navier-Stokes equations satisfy energy balances.

• Solutions satisfying the specified energy conditions are referred to as admissible or dissipative solutions.

• For any 0 < β < 1/3, there are infinitely many C^β initial data that give rise to infinitely many C^β admissible solutions of the 3D Euler equations.

• The proof of Theorem 1.3.2 (main result of thesis) cannot maintain the admissibility of the regular solution up to a fixed time and thus sacrifices regularity to restore admissibility on a fixed time interval.

• The existence of one approximate solution implies the existence of infinitely many solutions to the original system of PDEs.

• The Euler equations are recast in a specific form: { ∂_t v + div u + ∇p = 0; div v = 0; u = v ⊗̊ v = v ⊗ v − (1/n) Id |v|^2 }.

• λ_max denotes the maximum eigenvalue, and L^2_w is the space L^2 endowed with the weak topology.

• There exist infinitely many weak solutions v of the Euler equations (2.1.1.1) in [0,T)×R^n with pressure p = q0 − (1/n)|v|^2 such that v ∈ C([0,T];L^2_w), v(t,x) = v0(t,x) for t∈{0,T} a.e. x∈R^n, and (1/2)|v(t,x)|^2 = e(t,x)1Ω ∀t∈(0,T) a.e. x∈R^n.

• The strategy to prove Proposition 3.2.2.1 is to find a suitable complete metric space and prove that the desired solutions are residual.

• The construction aims for a sequence of subsolutions (vq, pq,Rq) such that the error Rq ≥ 0 is gradually removed.

• Only the traceless part R̊q matters for measuring the error from being an Euler solution.

• Perturbations are chosen to oscillate at frequency λq, leading to the bound ‖∇wq‖_0 ≲ δ^(1/2)_q λq.

• δq → 0 and λq → ∞, with λq at least an exponential rate.

• For the sake of definiteness, λq ∼ λ^q and δq ∼ λ^(−2β0)_q for some λ > 1 are imagined, though actual proofs require super-exponential growths.

• It is possible to send δq → 0 as q ↑ ∞ and obtain a relation between δq and λq.

• A profile W satisfying conditions (H1)-(H4) is found.

• It is crucial that c0 vanishes (content of H1).

• λq ∼ λ^q for some fixed λ ≥ 1.

• Real-valued ak are chosen, and Bk = B−k from Proposition 3.4.1 are satisfied.

• For k′ = −k, the integrals do not vanish.

• The set Λ of indices k is chosen such that −Λ⊆Λ.

• Beltrami flows are a well-known class of stationary solutions of the Euler equations.

• vk ∗ ⇀ ṽ and vk ⊗ vk ∗ ⇀ ṽ ⊗ ṽ + R̃ in L^∞ uniformly in time.

• The initial data of adapted subsolutions are automatically wild, assuming they satisfy an appropriate “admissibility condition”.

• From onwards, the prescription of an arbitrary kinetic energy profile is abandoned, and the generalized energy of the subsolutions (∫_T3 |v|^2(t,x)+trR(t,x)dx) is conserved across the iterations.

• A second intermediate step, “strong subsolutions,” is introduced from.

• For Nash error, ( v(t,x)⊗ v(t,x)−u(t,x)⊗u(t,x)+ R̊(t,x) ) dx−e(t)−− ∫_Td |u(t,x)|^2dx d/dt < σ.

• γ,ε > 0 and β ≥ 0 such that 2γ+β+ε ≤ 1.

• f ∈ C^0,2γ+β+ε.

• For every γ∈(0,1), ε > 0 such that 0 < γ+ε ≤ 1, and f as above.

• E1,E2 > 1.

• E is a family of smooth functions on with properties: (i) 1/2 ≤ e(t)≤ 1, (ii) e(0) is the same for every e∈E, (iii) e′(0) is the same for every e∈E, (iv) sup_e∈E ‖e‖_C1 = E1, (v) sup_e∈E ‖e‖_C2 = E2.

• A constant K > 1 is chosen for E1 = 2K + 2 and E2 = CK^2, and e′ ≤ −2K + 2 is required.

• The admissibility condition is ensured by choosing K large enough so that C K^γ < K−1.

• The strategy in (for θ < 1/3) requires local existence and uniqueness results for solutions of fractional Navier-Stokes, as well as estimates for their norms.

• An averaging process is linear and commutes with derivatives.

• For C^β-adapted subsolutions: γ,Ω > 0, 0 < β < 1/3, and ν satisfies ν > (1-3β)/(2β).

• Initial datum v(0, ·)∈C^β(T3) and R(0, ·)≡ 0.

• For all t > 0, ρ(t) > 0.

• There exist α∈(0,1) and C ≥ 1 such that ‖v‖_1+α ≤ CΩ^(1/2)ρ^(−(1+ν)) and |∂_tρ| ≤ CΩ^(1/2)ρ^(−ν).

• The convex integration strategy adopted by in the Euler setting is followed.