Circular Astronomy

Twitter List – See all the findings and discussions in one place

-

The Mysterious Discovery of JWST That No One Saw Coming

Are We Inside a Cosmic Whirlpool? Recent JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES) observations of mysterious cosmological anomalies in the rotational patterns of galaxies challenge our understanding of the universe and reveal surprising connections to natural growth patterns.

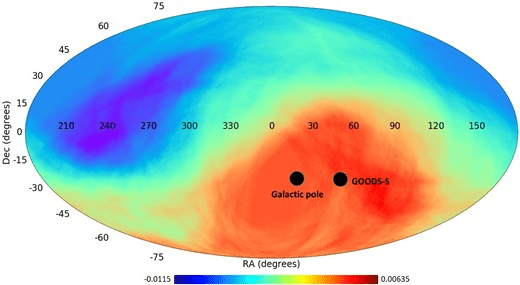

The rotation of 263 galaxies has been studied by Lior Shamir of Kansas State University, with 158 rotating clockwise and 105 rotating counterclockwise. The number of galaxies rotating in the opposite direction relative to the Milky Way is approximately 1.5 times higher than those rotating in the same direction.

New Cosmological anomalies that challenge our cosmological models and would have angered Einstein.

This observation challenges the expectation of a random distribution of galaxy rotation directions in the universe based on the isotropy assumption of the Cosmological Principle.

This is certainly not something Einstein would have liked to hear during his lifetime, but it would have excited Johannes Kepler.

What does this mean for our cosmological models, and why would it make Johannes Kepler happy?

The 1.5 ratio in galaxy rotation bias is intriguingly close to the Golden Ratio of 1.618. The Golden Ratio was one of Johannes Kepler’s two favorites. The astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) referred to the Golden Ratio as one of the “two great treasures of geometry” (the other being the Pythagorean theorem). He noted its connection to the Fibonacci sequence and its frequent appearance in nature.

What is the Fibonacci sequence?

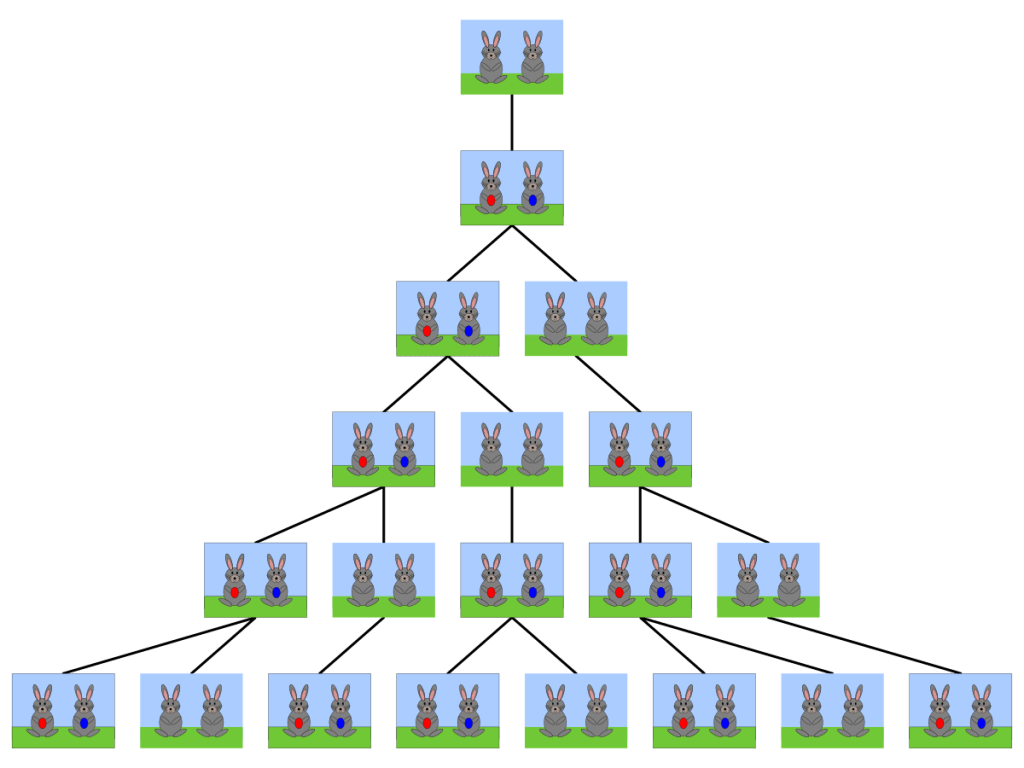

The Italian mathematician Leonardo of Pisa, better known as Fibonacci, introduced the world to a fascinating sequence in his 1202 book Liber Abaci (The Book of Calculation). This sequence, now famously known as the Fibonacci sequence, was presented through a hypothetical problem involving the growth of a rabbit population.

The growth of a rabbit population and why it matters?

Fibonacci posed the following question: Suppose a pair of rabbits can reproduce every month starting from their second month of life. If each pair produces one new pair every month, how many pairs of rabbits will there be after a year?

The solution unfolds as follows:

- In the first month, there is 1 pair of rabbits.

- In the second month, there is still 1 pair (not yet reproducing).

- In the third month, the original pair reproduces, resulting in 2 pairs.

- In the fourth month, the original pair reproduces again, and the first offspring matures and reproduces, resulting in 3 pairs.

Image Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FibonacciRabbit.svg

This pattern continues, with each new generation adding to the total, where each term is the sum of the two preceding terms.

The Fibonacci sequence generated is: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, …

While this idealized model of a rabbit population assumes perfect conditions—no sickness, death, or other factors limiting reproduction—it reveals a growth pattern that approaches the Golden Ratio as the sequence progresses. The ratio is determined by dividing the current population by the previous population. For example, if the current population is 55 and the previous population is 34, based on the Fibonacci sequence above, the ratio of 55/34 is approximately 1.618.

However, in reality, the growth rate of a rabbit population would likely fall below this mathematical ideal ratio due to natural constraints.Yet, this growth (evolutionary) pattern appears quite often in nature, such as in the growth patterns of succulents.

The growth patterns in succulents often follow the Fibonacci sequence, as seen in the arrangement of their leaves, which spiral around the stem in a way that maximizes sunlight exposure. This spiral phyllotaxis reflects Fibonacci numbers, where the number of spirals in each direction typically corresponds to consecutive terms in the sequence.

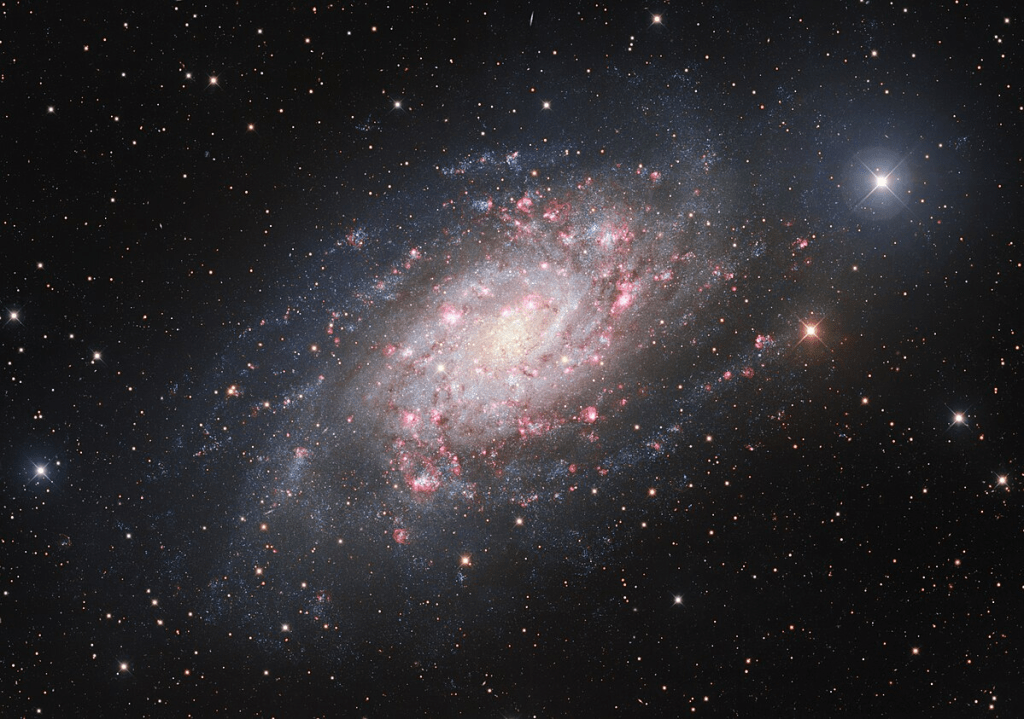

Spiral galaxies exhibit a similar growth (evolutionary) pattern in their spiral arms.

Spiral galaxies, like the Milky Way, display strikingly similar growth patterns in their spiral arms, where new stars are continuously formed and not in the center of the galaxy.

Image Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_Galaxy_of_Birth_and_Death.jpg

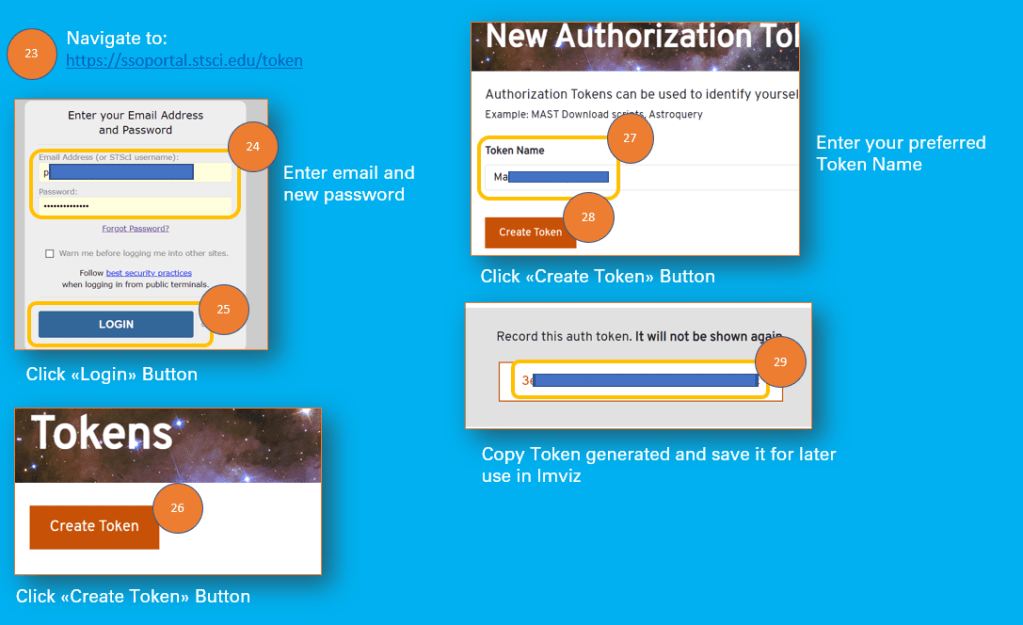

Returning to the observations and research conducted by Lior Shamir of Kansas State University using the JWST.

The most galaxies with clockwise rotation are the furthest away from us.

The GOODS-S field is at a part of the sky with a higher number of galaxies rotating clockwise

Image Source: Figure 10 https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staf292

“If that trend continues into the higher redshift ranges, it can also explain the higher asymmetry in the much higher redshift of the galaxies imaged by JWST. Previous observations using Earth-based telescopes e.g., Sloan Digital Sky Survey, Dark Energy Survey) and space-based telescopes (e.g., HST) also showed that the magnitude of the asymmetry increases as the redshift gets higher (Shamir 2020d).” Source: [1]“It becomes more significant at higher redshifts, suggesting a possible link to the structure of the early universe or the physics of galaxy rotation.” Source: [1]

Could the universe itself be following the same growth patterns we see in nature and spiral galaxies?

This new observation by Lior Shamir is particularly intriguing because, if we were to shift the perspective of our standard cosmological model—from one based on a singularity (the Big Bang ‘explosion’), which is currently facing a lot of challenges [2], to a growth (evolutionary) model—we would no longer be observing the early universe. Instead, we would be witnessing the formation of new galaxies in the far distance, presenting a perspective that is the complete opposite of our current worldview (paradigm).

NEW: Massive quiescent galaxy at zspec = 7.29 ± 0.01, just ∼700 Myr after the “big bang” found.

RUBIES-UDS-QG-z7 galaxy is near celestial equator.

It is considered to be a “massive quiescent galaxy’ (MQG).

These galaxies are typically characterized by the cessation of their star formation.

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/adab7a

The rotation, whether clockwise or counterclockwise, has not yet been observed.Reference

The distribution of galaxy rotation in JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey

Lior Shamir

[1 ] https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/538/1/76/8019798?login=false

The Hubble Tension in Our Own Backyard: DESI and the Nearness of the Coma Cluster

Daniel Scolnic, Adam G. Riess, Yukei S. Murakami, Erik R. Peterson, Dillon Brout, Maria Acevedo, Bastien Carreres, David O. Jones, Khaled Said, Cullan Howlett, and Gagandeep S. Anand

[2] https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2041-8213/ada0bd

Reading Recommendation:

The Golden Ratio, Mario Livio, 2002

Mario Livio was an astrophysicist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, which operates the Hubble Space Telescope.

RUBIES Reveals a Massive Quiescent Galaxy at z = 7.3

Andrea Weibel, Anna de Graaff, David J. Setton, Tim B. Miller, Pascal A. Oesch, Gabriel Brammer, Claudia D. P. Lagos, Katherine E. Whitaker, Christina C. Williams, Josephine F.W. Baggen, Rachel Bezanson, Leindert A. Boogaard, Nikko J. Cleri, Jenny E. Greene, Michaela Hirschmann, Raphael E. Hviding, Adarsh Kuruvanthodi, Ivo Labbé, Joel Leja, Michael V. Maseda, Jorryt Matthee, Ian McConachie, Rohan P. Naidu, Guido Roberts-Borsani, Daniel Schaerer, Katherine A. Suess, Francesco Valentino, Pieter van Dokkum, and Bingjie Wang (王冰洁)

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/adab7a

Appendix Spiral Galaxies:

Spiral galaxies are known for their stunning and symmetrical spiral arms, and many of them exhibit patterns that approximate logarithmic spirals, which are mathematically related to the Golden Ratio. While not all spiral galaxies perfectly follow the Golden Ratio, some exhibit spiral arm structures that closely resemble this pattern. Here are some notable examples of spiral galaxies with logarithmic spiral patterns:

1. Milky Way Galaxy

- Our own galaxy, the Milky Way, is a barred spiral galaxy with arms that approximate logarithmic spirals. The four primary spiral arms (Perseus, Sagittarius, Scutum-Centaurus, and Norma) follow a logarithmic pattern, though not perfectly aligned with the Golden Ratio.

2. M51 (Whirlpool Galaxy)

- The Whirlpool Galaxy is one of the most famous examples of a spiral galaxy with well-defined logarithmic spiral arms. Its arms are nearly symmetrical and exhibit a pattern that closely resembles the Golden Ratio.

3. M101 (Pinwheel Galaxy)

- The Pinwheel Galaxy is a grand-design spiral galaxy with prominent and well-defined spiral arms. Its structure is often cited as an example of a logarithmic spiral in astronomy.

4. NGC 1300

- NGC 1300 is a barred spiral galaxy with a striking logarithmic spiral pattern in its arms. It is often studied for its near-perfect spiral structure.

5. M74 (Phantom Galaxy)

- The Phantom Galaxy is another grand-design spiral galaxy with arms that follow a logarithmic spiral pattern. Its symmetry and structure make it a textbook example of this phenomenon.

6. NGC 1365

- Known as the Great Barred Spiral Galaxy, NGC 1365 has a prominent bar structure and spiral arms that exhibit a logarithmic pattern.

7. M81 (Bode’s Galaxy)

- Bode’s Galaxy is a spiral galaxy with arms that follow a logarithmic spiral structure. It is one of the brightest galaxies visible from Earth and a popular target for astronomers.

8. NGC 2997

- This galaxy is a grand-design spiral galaxy with arms that closely resemble logarithmic spirals. It is located in the constellation Antlia.

9. NGC 4622

- Known as the “Backward Galaxy,” NGC 4622 has a unique spiral structure with arms that follow a logarithmic pattern, though its rotation direction is unusual.

10. M33 (Triangulum Galaxy)

- The Triangulum Galaxy is a smaller spiral galaxy with arms that exhibit a logarithmic spiral structure. It is part of the Local Group, along with the Milky Way and Andromeda.

-

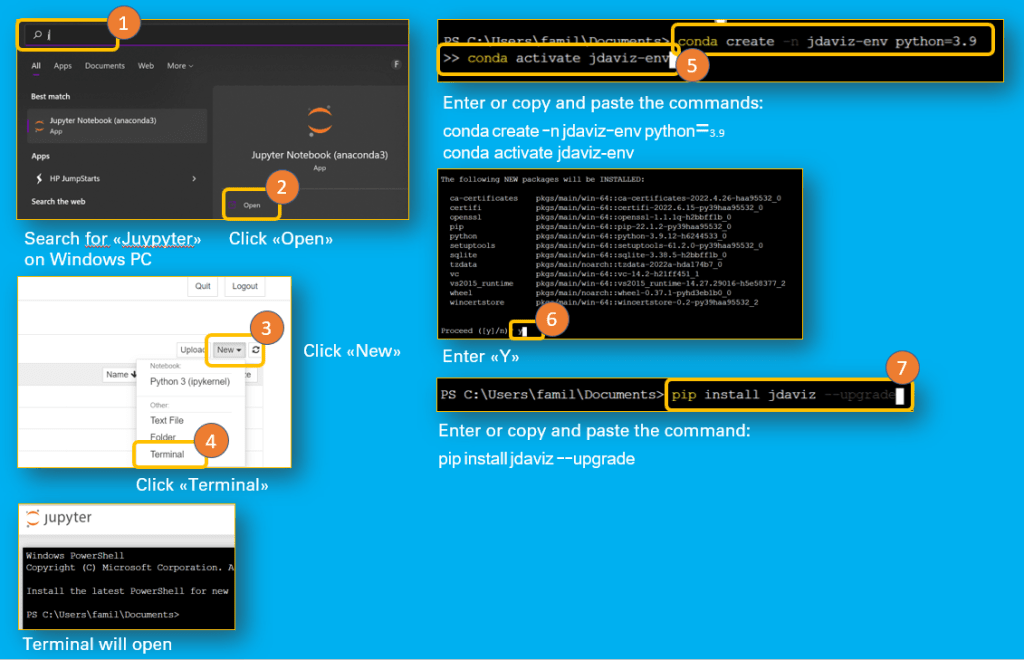

How to Download, View, And Edit Images from the James Webb Space Telescope with Jdaviz and Imviz

Like to comfortably view and edit images from the Jamew Webb Space Telescope like an astronomer ?

Then follow this step by step cheatsheet guides if you are using windows on a PC .

Main Software Components

There are three key software components required:

- Microsoft C++ 14

- Jupyter Notebook (Python)

- Jdaviz

Additonal

- MAST Token to be able to download the images with Imviz.

Prerequsites:

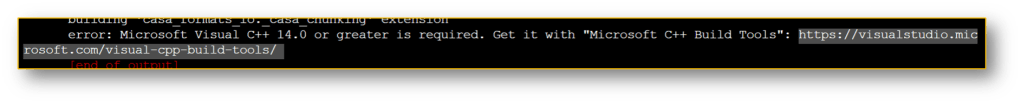

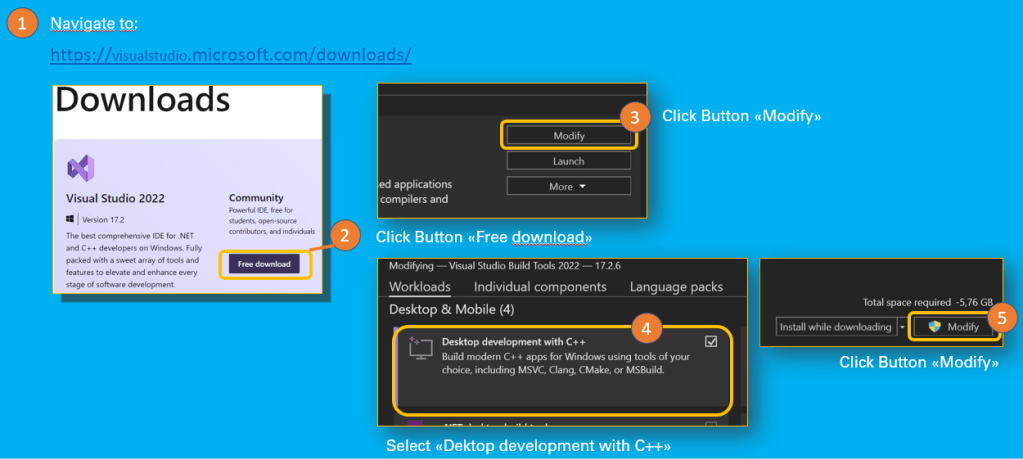

Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater

error: Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater is required If Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater is not installed, the installation of Jdaviz will fail. Without Jdaviz the downloaded images from the James Webb Space Telescope cannot be edited.

How to install Microsoft Visual C++

- Navigate to: https://visualstudio.microsoft.com/downloads/

- Download Visual Studio 2022 Community version

- Follow the instructions in this post: Install C and C++ support in Visual Studio | Microsoft Docs

Cheatsheet: Install Visual Studio 2022 MAST Token

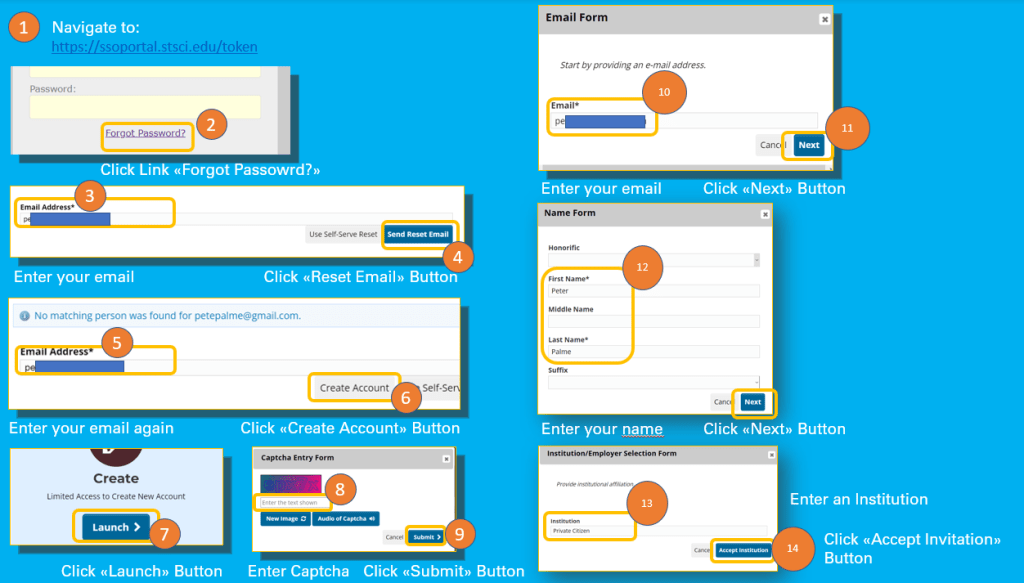

- Navigate to https://ssoportal.stsci.edu/token

If you do not have not an account yet, please follow below steps to create your account:

- Click on the Forgotten Password? link

- Enter your email Adress

- Click Send Reset Email Button

- Click Create Account Button

- Click Launch Button

- Enter the Captcha

- Click Submit Button

- Enter your email

- Click Next Button

- Fill in the Name Form

- Click Next Button

- Fill in the Insitution (e.g. Private Citizen or Citizen Scientist)

- Click Accept Institution Button

- Enter Job Title (whatever you are or like to be ;-))

- Click Next Button

- New Account Data for your review is presented, in case of missing contact data, step 17 might be necessary

- Fill in Contact Information Form

- Click Next Button

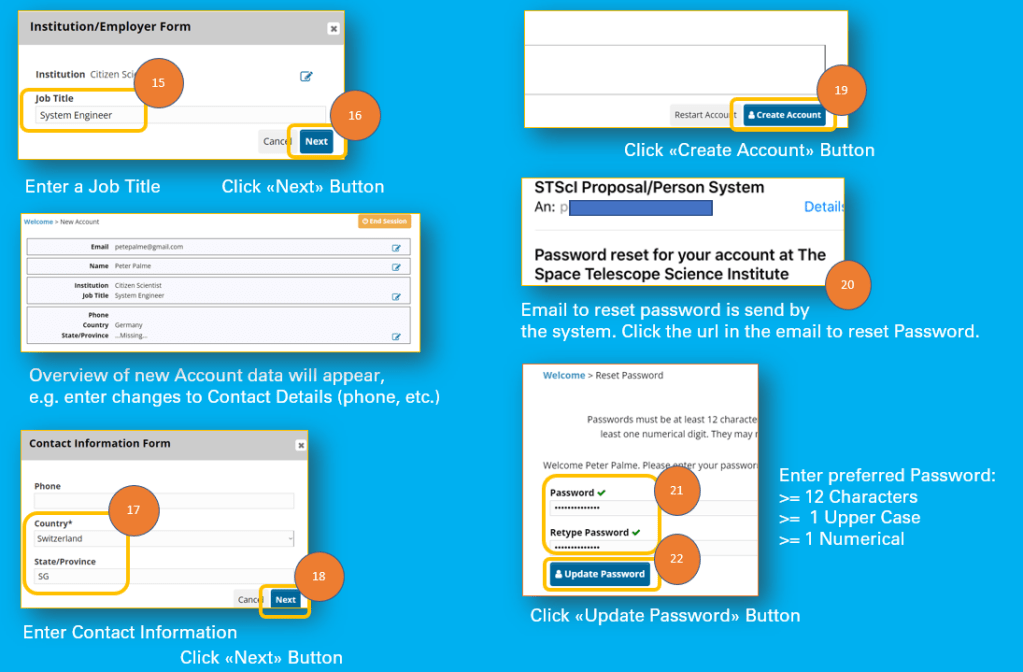

- Click Create Account Button

- In your email account open the reset password emal

- Click on the link

- Enter Password

- Enter Retype Password

- Click Update Password

- Navigate to https://ssoportal.stsci.edu/token

- Now log on with your email and new account password

- Click Create Token Button

- Fill in a Token Name of your choice

- Click Create Token Button

- Copy the Token Number and save it for later use in Imviz to download the images from the James Webb Space Telescope

Quite a lot of steps for a Token.

Cheatsheet: Create MAST Account

Cheatsheet: Set Passord for new Account

Cheatsheet: Create MAST Token for use in Imviz Jupyter Notebook

Jupyter notebook comes with the ananconda distribution.

- Navigate to: https://www.anaconda.com/products/distribution#windows

- Follow the instructions at: https://docs.anaconda.com/anaconda/install/windows/

Install Jdaviz

- Navigate to: Installation — jdaviz v2.7.2.dev6+gd24f8239

- Open the Jupyter Notebook

- Open Terminal from Jupyter Notebook

- Follow the instruction in: Installation — jdaviz v2.7.2.dev6+gd24f8239

Cheatsheet: Install Jdaviz How to use IMVIZ

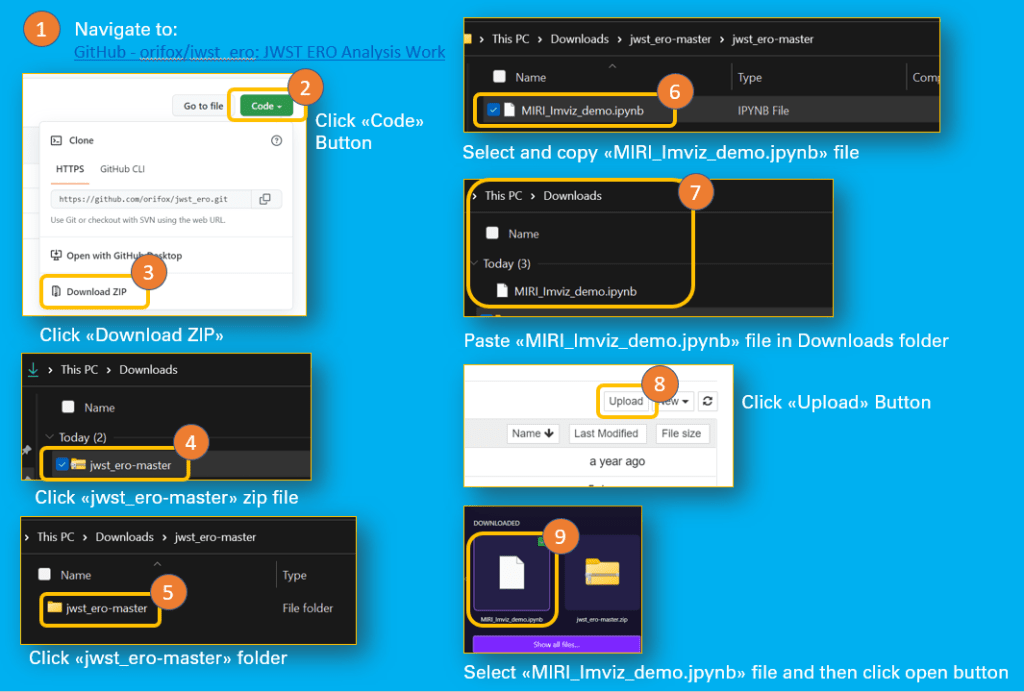

Imviz is installed together with Jdaviz.

Following steps to take in order to use Imviz:

- Navigate to: GitHub – orifox/jwst_ero: JWST ERO Analysis Work

- Click Code Button

- Click Download Zip

- If you do not have unzip, then the next steps might work for you:

- In Download Folder (PC) click the jwst_ero master zip file

- Then click on the folder jwst_ero master

- Copy file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb

- Paste the file in the download folder

- Open Jupyter notebook

- Click Upload Button

- Select the file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb

- Click Open Button

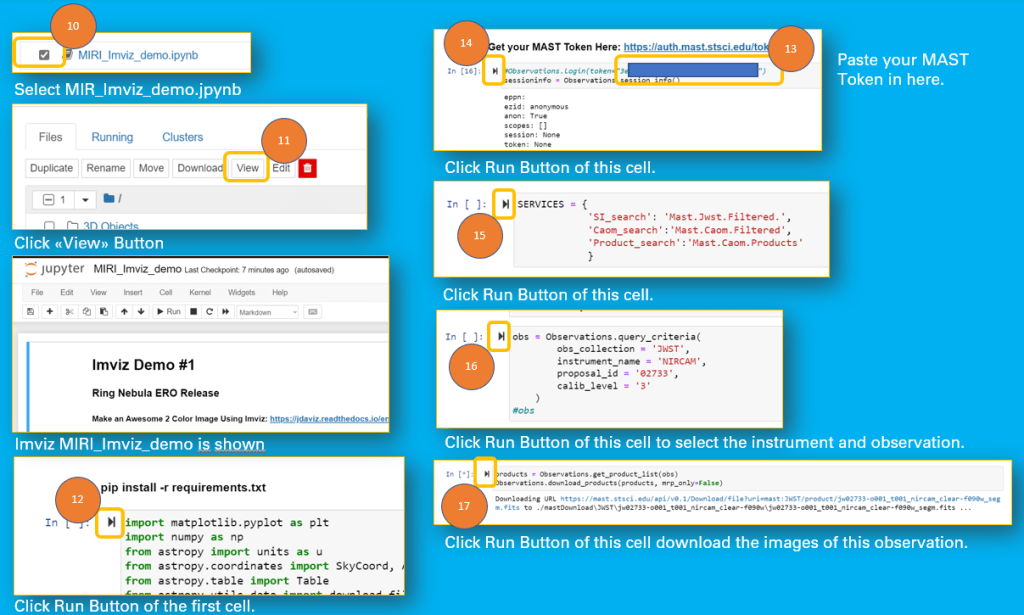

- Select the file MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb in the Jupyter Notebook file list

- Click View Button

- Click Run Button First Cell

- Paste MAST Token in next cell

- Click Run Button of this Cell

- Click then Run Button of next Cell

- Click Run Button of the following Cell

- Click Run Button of the next Cell to download the images

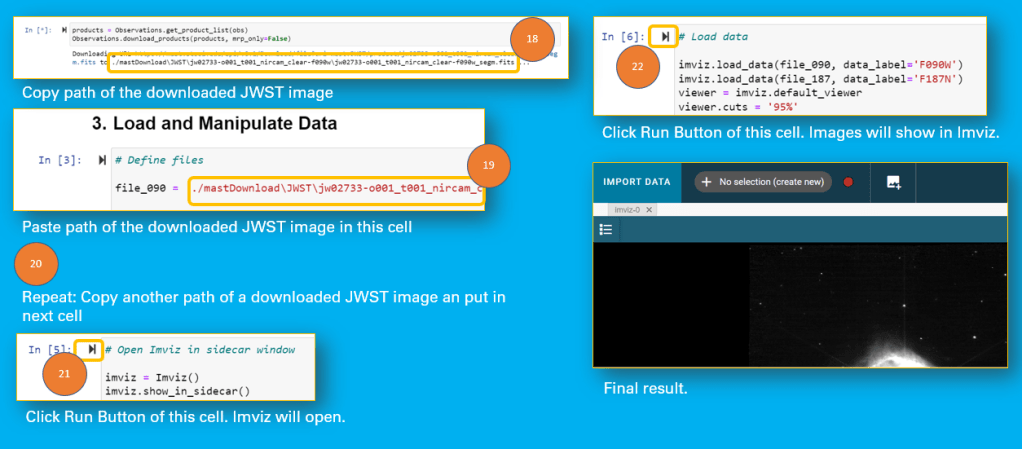

- Copy the link to the downloaded image file

- Past link into the First Cell in 3. Load and Manipulate Data

- Do the same in the next Cell

- Click Run Button of the Cell to open Imviz

- Click Run Button on the next Cell to load images in Imviz

Cheatsheet: Upload MIRI_Imviz_demo.jpynb in Jupyter notebook Now all set to download the images of the JWST observation:

Cheatsheet: Download JWST images with Imviz And now all is set to open and edit the images in Imviz

Cheatsheet: Open Images in Imviz And finally you are ready to follow the video tutorials in order to learn how to use Imviz to manipulate the JWST images.

Video Tutorials for Imviz:

And this is the master Ori Fox of the Imviz demo notebook file if you like to follow him on Twitter

-

Time for a new scientific debate – Accretion vs Convection

To what degree is gravity needed to form structures in space? While many believe that celestial bodies (stars, planets, moons, meteoroids) can only form through gravitational attraction in the vacuum of space, I believe that these bodies form through a thermodynamic process similar to the formation of hydrometeors (e.g., hail). This is because our solar system possesses a boundary layer, a discovery made by the Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) mission in 2013.

In simple terms: Planets, moons, and small bodies are formed within convection cells created by the jet streams of a young sun, under the influence of strong magnetic fields.

Recently, a new paper introduced quantum models in which gravity emerges from the behavior of qubits or oscillators interacting with a heat bath.

More details and link to the research paper: On the Quantum Mechanics of Entropic Forces

https://circularastronomy.com/2025/10/09/entropic-gravity-explained-how-quantum-thermodynamics-could-replace-gravitons/ -

Formalhaut A with First Asteroid Belt Seen Outside Solar System

Fomalhaut A is a bright star and was known to the Persian and Arabic Astronomers. The name of the star is Arabic and means “mouth of the fish”. It belongs to a Tripple Star System 25 light-years away from earth.

Formalhaut A has several notable characteristics:

- Location and visibility: It is the brightest star in the constellation Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish) and one of the brightest stars in the night sky. Fomalhaut is often called the “Autumn Star” or “Loneliest Star” due to its solitary appearance in a relatively empty region of the sky.

- It is part of a triple star system, with two companion stars: Fomalhaut B (TW Piscis Austrini) and Fomalhaut C.

- Physical characteristics: Fomalhaut A is a main sequence star slightly larger than the Sun. It is considerably more luminous, shining about 16 times brighter than the Sun in visible light.

- Age: The star is relatively young, with an estimated age of 400-450 million years.

- Debris disk: Fomalhaut A is surrounded by a massive and complex debris disk, first detected in the 1980s and later imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope. This disk is composed of multiple rings or belts of different materials and is not centered on the star itself.

- Planetary system: In 2008, astronomers announced a potential extrasolar planet candidate orbiting Fomalhaut A. However, subsequent observations suggested this object, known as Fomalhaut b, may actually be the debris from a collision between two large bodies rather than a planet.

- Cultural significance: Fomalhaut has played a role in various cultures throughout history. Its name derives from Arabic, meaning “mouth of the fish,” and it was considered one of the four “royal stars” by ancient Persians.

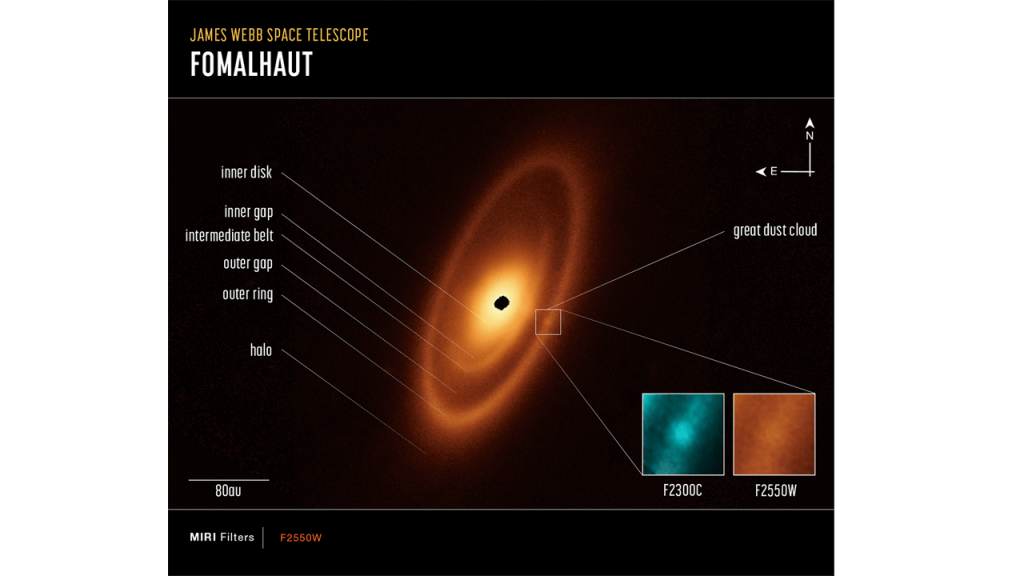

Fomalhaut Dusty Debris Disk (MIRI Image), James Webb Telescope first image of a protoplanetary disk.

Astronomers used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to image the warm dust around Fomalhaut, revealing three nested belts extending out to 14 billion miles (23 billion kilometers) from the star. These belts are analogous to debris disks found elsewhere in our galaxy and provide insights into planetary system formation. The inner belts, which had never been seen before, were revealed by Webb for the first time. Overall, Fomalhaut’s dusty structures are much more complex than the asteroid and Kuiper dust belts in our solar system.

Credits: NASA, ESA, CSA, A. Gáspár (University of Arizona). Image processing: A. Pagan (STScI) Link

Astronimcal filters used in the JWST image above

F2300C can also represent a specific filter used in astronomy with the Mid-InfraRed Instrument (MIRI) on the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). This filter allows astronomers to observe objects at a specific infrared wavelength (around 22.75 micrometers) to study faint celestial bodies.

F2550W refers to a specific filter used in astronomy with the Mid-InfraRed Instrument (MIRI) on the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

- 2550: Indicates the central wavelength of the filter in nanometers (nm). In this case, it’s around 2.55 micrometers (µm).

- W: Potentially stands for “Wide” bandpass, suggesting the filter captures a broader range of infrared wavelengths around the central point.

This filter allows astronomers to observe celestial objects in the mid-infrared spectrum, specifically around 2.55 micrometers. This wavelength range is useful for studying faint and distant objects, such as:

- Cool stars and brown dwarfs

- Dust clouds surrounding young stars

- Interstellar gas and dust

- The atmospheres of exoplanets (planets outside our solar system)

Scientists use data collected through F2550W alongside observations from other JWST filters to:

- Understand the formation and evolution of stars and planetary systems

- Characterize the composition of interstellar dust and gas

- Analyze the atmospheres of exoplanets and search for potential signs of habitability

References:

Fomalhaut: Not So Lonely After Allhttps://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov/news-display.cfm?News_ID=1002

Fomalhaut is the loneliest star in the southern sky

https://earthsky.org/brightest-stars/solitary-fomalhaut-guards-the-southern-sky/ -

HL Tau Protoplanetary Disk Contains More Water Than Earth

The observations show that there is at least three times more water in the inner disc of the young Sun-like star HL Tauri than in all of Earth’s oceans combined.HL Tau also called HL Tauri is a young T Tauri star located approximately 450 light-years away from earth in the Taurus Molecular Cloud. It is surrounded by a protoplanetary disk that exhibits a series of concentric bright rings separated by gaps, as revealed by high-resolution observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA).

Location of HL Tau in the Taurus Molecular Cloud

https://twitter.com/universal_sci/status/1762962965446180910

Taurus Molecular Cloud Gas Dynamics:

Protoplanetary Disk Structure

The striking ring-like structures observed in the HL Tau disk are believed to be indicators of ongoing planet formation processes. The gaps in the disk may be carved out by forming planets, while the bright rings could be regions of higher dust density where planet formation is occurring. The presence of these features suggests that planet formation may happen more rapidly than previously thought, as the HL Tau system is estimated to be less than 100,000 years old.

Disk Properties and Modeling

Detailed radiative transfer modeling of the dust emission from the HL Tau disk has been conducted to derive its surface density profile and structure. The modeling results indicate a radial gradient in the dust grain size distribution, with larger grains present in the inner disk regions.

Theoretical studies have explored the possibility of planet formation in the HL Tau disk, considering various planet trapping mechanisms and disk models with different initial masses. These simulations suggest that the prominent gaps and rings observed in the disk could indeed be associated with the formation of planets, particularly at the locations of volatile ice lines.

Water detected with ALMA

Three times more water than the Earth’s oceans!

Outflows and Jets

In addition to the protoplanetary disk, HL Tau is also known to exhibit bipolar outflows and jets of gas, such as the Herbig-Haro object HH 150. These outflows are emitted along the rotational axis of the disk and interact with the surrounding interstellar material, producing observable features.

Overall, the HL Tau system provides a unique opportunity to study the early stages of planet formation and the evolution of protoplanetary disks, thanks to the detailed observations and modeling efforts enabled by advanced telescopes like ALMA.

References:

The properties of the inner disk around HL Tau: Multi-wavelength modeling of the dust emissionYao Liu, Thomas Henning, Carlos Carrasco-González, Claire J. Chandler, Hendrik Linz, Til Birnstiel, Roy van Boekel, Laura M. Pérez, Mario Flock, Leonardo Testi, Luis F. Rodríguez and Roberto Galván-Madrid

Issue A&AVolume 607, November 2017 Article Number A74 Number of page(s) 10 Section Interstellar and circumstellar matter DOI https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201629786 Published online 16 November 2017 https://www.aanda.org/articles/aa/full_html/2017/11/aa29786-16/aa29786-16.html

Physics of planet trapping with applications to HL Tau

Alexander J Cridland, Ralph E Pudritz, Matthew Alessi

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 484, Issue 1, March 2019, Pages 345–363, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stz008

Published: 05 January 2019

https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/484/1/345/5274147On planet formation in HL Tau

Giovanni Dipierro, Daniel Price, Guillaume Laibe, Kieran Hirsh, Alice Cerioli, Giuseppe Lodato

https://academic.oup.com/mnrasl/article/453/1/L73/983336

Astronomers reveal a new link between water and planet formation

Resolved ALMA observations of water in the inner astronomical units of the HL Tau disk

Stefano Facchini, Leonardo Testi, Elizabeth Humphreys, Mathieu Vander Donckt, Andrea Isella, Ramon Wrzosek, Alain Baudry, Malcom D. Gray,

Anita M. S. Richards & Wouter Vlemmmingshttps://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-024-02207-w

The winds from HL Tau

-

Young Star HH 211 with Bipolar Jets is a Source of Molecular Emission

HH 211 is a young bipolar protostellar outflow that provides insights into the early stages of star formation. Here are the key points about HH 211 from the search results:

Molecular Emission

HH 211 is a prominent source of molecular emission, particularly molecular hydrogen (H2), which traces the outflow’s shocked molecular gas. The molecular emission dominates in this young outflow, suggesting lower shock velocities that do not fully dissociate molecules.

Outflow Structure

HH 211 exhibits a bipolar outflow structure, with jets and cavities carved out by the outflow. Hubble Space Telescope images reveal the atomic and ionized components of the outflow, traced by emission lines like Hα, [SII], [NII], and [FeII].

Young Evolutionary Stage

HH 211 is classified as a Class 0 or Class I protostellar source, representing the earliest stages of star formation. Studying young outflows like HH 211 provides insights into the ejection processes that govern the formation of stars and their associated outflows.

Shock Excitation

The molecular and atomic emission lines observed in HH 211 are excited by shocks associated with the protostellar outflow. These shock-excited lines serve as diagnostics for understanding the physical conditions and kinematics of the outflow.In summary, HH 211 is a remarkable example of a young protostellar outflow, rich in molecular emission and exhibiting a bipolar structure. Its study offers valuable insights into the early stages of star formation and the ejection processes that drive outflows.

References:

Molecular emission in regions of star formation

Antoine Gusdorf. Molecular emission in regions of star formation. Astrophysics [astro-ph]. Université

Paris Sud – Paris XI, 2008. English. ffNNT : ff. fftel-00370141fThe anatomy of the young protostellar outflow HH 211

A. Tappe, J. Forbrich, S. Martín, Y. Yuan, C. J. Lada

- April 2012

- The Astrophysical Journal 751(1):9

- April 2012

- 751(1):9

HH 211: Jets from a Forming Star

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Webb; Processing: Tom Ray (DIAS Dublin)

-

Very-Low-Mass Star ISO-Chal 147 with Abundant Hydrocarbons in Protoplanetary Disk

ISO-Chal-1471 is a young, low-mass star located approximately 600 light-years away from Earth. ISO-Chal 147 is located in the Chamaeleon I star-forming cloud. It is a red dwarf star, which is a type of star that is very common in the Milky Way and burns through fuel slowly. Here are the key points from recent studies using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST):

Protoplanetary Disk:

- ISO-Chal-147 has a protoplanetary disk of gas around it which s rich in carbon-based molecules, including hydrocarbons. This is surprising because most young stars have disks that are rich in oxygen-based molecules.

- The star’s age is 1 to 2 million years, and its mass is 11% of our Sun’s.

- Protoplanetary disks around low-mass stars are challenging to study due to their smaller size and lower brightness.

Hydrocarbon Molecules:

- The JWST detected an unusually high amount of hydrocarbon molecules in ISO-Chal-147’s disk.

- Hydrocarbon molecules contain carbon atoms.

- Such disks may give birth to planets that are poor in carbon, similar to Earth.

- Disks around Sun-like stars tend to be carbon-poor and rich in oxygen-containing molecules.

- Hydrocarbon molecules (Methane, CH4; Ethane, C2H6; Ethylene, C2H2; Diacetylene, C4H2; Propyne, C3H4; Benzene, C6H6)

- First extrasolar detection of ethane (C2H6), the largest fully-saturated hydrocarbon detected outside our Solar System

Implications:

- Understanding protoplanetary disks around low-mass stars helps us learn about planet formation in different contexts.

- Collaborations across disciplines, like astronomy and chemistry, contribute to scientific progress.

References:

New insights about protoplanetary disks around low-mass stars – Department of Astronomy (su.se)

Webb identifies surprising carbon-rich ingredients around young star

-

Dracula’s Chivito (IRAS 23077+6707) Largest Known Protoplanetary Disk with Carbon-Based Molecules

Dracula’s Chivito, also known as IRAS 23077+6707, is the largest known disk of its kind. It was discovered during a study of active galactic nucleus candidates using images from the Pan-STARRS research project. This edge-on disk completely obscures its central star and is associated with an infrared light source in the same region of the sky. The disk spans approximately 11 arcseconds in apparent size, with a faint structure extending out to about 17 arcseconds in the northern part, giving it a resemblance to a sandwich with fang-like structures. This similarity, along with its association with the infrared source IRAS 23077+6707, earned it the nickname “Dracula’s Chivito” (chivito being a type of sandwich from Uruguay).

The protoplanetary disk surrounds a young star about twice the size of our sun, and the system isn’t located near any known star-forming regions. Analysis suggests it’s a young system at the end of a developmental phase. It has faint “fangs” in the north that might be a dissipating envelope, further supporting its youth.

The discovery of Dracula’s Chivito is significant because it confirms the existence of an entirely new type of object, previously seen only once before in the “Gomez’s Hamburger” nebula. Initially thought to be a nebula, Gomez’s Hamburger was later revealed to be a protoplanetary disk similar to Dracula’s Chivito, but much hotter and more evolved.

References:

A Vampire’s Sandwich Filled with Gas and Dust

Authors: Ciprian T. Berghea et al.

First Author’s Institution: US Naval Observatory

Status: Published in ApJLStrange Object Described as Dracula’s Sandwich Could Represent a New Kind of Baby Star

Dracula’s Chivito: discovery of a large edge-on protoplanetary disk with Pan-STARRS

Ciprian T. Berghea, Ammar Bayyari, Michael L. Sitko, Jeremy J. Drake, Ana Mosquera, Cecilia Garraffo, Thomas Petit, Ray W. Russell, Korash D. Assani

Comments: 11 pages, 4 figures, accepted in ApJL Subjects: Solar and Stellar Astrophysics (astro-ph.SR); Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP) Cite as: arXiv:2402.01063 [astro-ph.SR] (or arXiv:2402.01063v2 [astro-ph.SR] for this version) https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.01063 https://arxiv.org/html/2402.01063v1

The infrared emission bands. III. Southern IRAS sources

M Cohen 1, A G Tielens, J Bregman, F C Witteborn, D M Rank, L J Allamandola, D H Wooden, M de Muizon

Collaborators, Affiliations expand

- PMID: 11542167

- DOI: 10.1086/167489

-

Star TW Hydrae with Protoplanetary Disc

TW Hydrae is a young T Tauri star located about 196 light-years away in the constellation Hydra. It is surrounded by a protoplanetary disk.

Protoplanetary Disk

- The disk extends from around 1-30 AU from the star and has a large inner cavity or gap extending out to around 2.3 AU.

- The disk shows evidence of multiple snow lines where different volatile molecules like water, carbon monoxide, and methane freeze out and condense onto dust grains.

- ALMA observations have detected the carbon monoxide snow line at around 30 AU, where the diazenylium molecule is concentrated, tracing the edge of the CO snow region.

- The disk has been resolved at high resolution, revealing a series of bright and dark rings.

Chemical Composition

- The inner disk (< 2.3 AU) is depleted in carbon and oxygen, with abundances around 50 times lower than the interstellar medium values.

- This depletion suggests that volatile-rich icy grains are efficiently trapped outside the water ice line, preventing enrichment of the inner disk.

- If CO is the main carbon carrier in ices, dust needs to be trapped efficiently outside the CO ice line at around 20 AU to explain the low C/H ratio.

- Observations of deuterated species like DCN, DCO+, and N2D+ show enhancements at specific disk radii, tracing chemical processes like CO depletion and deuterium fractionation.

The TW Hydrae disk provides a detailed look at the chemical environment where planets are forming, with clear evidence of snow lines, dust evolution, and volatile depletion shaping the composition of potential planets.

References:

The dry and carbon-poor inner disk of TW Hydrae: evidence for a massive icy dust trap

Issue A&AVolume 632, December 2019 Article Number L10 Number of page(s) 5 Section Letters to the Editor DOI https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201936638 Published online 10 December 2019 A Frosty Landmark for Planet and Comet Formation

https://science.nasa.gov/universe/exoplanets/a-frosty-landmark-for-planet-and-comet-formation/

RESOLVING THE CHEMISTRY IN THE DISK OF TW HYDRAE. I. DEUTERATED SPECIES

Chunhua Qi, David J. Wilner, Yuri Aikawa, Geoffrey A. Blake, and Michiel R. Hogerheijde

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1086/588516/pdf

Resolving the chemistry in the disk of TW Hydrae I. Deuterated species

Comments: 12 pages, 12 figures, accepted to ApJ Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph) Cite as: arXiv:0803.2753 [astro-ph] (or arXiv:0803.2753v1 [astro-ph] for this version) https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.0803.2753Focus to learn more Related DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/588516 -

Circumstellar Disk Around Star PDS 70

PDS 70 is a young T Tauri star located about 370 light-years away in the constellation Centaurus. It is surrounded by a protoplanetary disk with a large gap extending from around 65 to 140 AU. Image also shows the PDS 70 cexoplanets.

Planetary System

- PDS 70b: A gas giant planet with a mass a few times that of Jupiter, orbiting at around 20.8 AU from the star. It has a temperature of around 1,200K. It is observationally confirmed to have its own circumplanetary disk.

- PDS 70c: Another gas giant planet with a mass around 7.5 Jupiter masses, orbiting at 34.3 AU in a near 1:2 orbital resonance with PDS 70b. Its radius is estimated to be around 2 Jupiter radii.

Protoplanetary Disk

- The disk has an inner cavity extending out to around 65 AU, with larger dust grains cleared out to 80 AU.

- Observations with ALMA have detected emission from 12 different molecular species (CO, H2CO, C2H, HCN, etc.) primarily originating from a bright ring outside the planets’ orbits, indicating a chemically rich environment.

- The molecular emission shows radial variations.

- The high C2H/13CO ratio and lower limits on N(CS)/N(SO) indicate the disk likely has a C/O ratio greater than 1.

- Water vapor has been detected in the inner disk region inside the cavity using JWST, indicating the conditions may be suitable for terrestrial planet formation.

The PDS 70 system provides a rare opportunity to study ongoing planet formation and the chemical links between a planet’s birth environment and its atmospheric composition.

References:

Water in the terrestrial planet-forming zone of the PDS 70 disk

Perotti, G., Christiaens, V., Henning, T. et al. Water in the terrestrial planet-forming zone of the PDS 70 disk. Nature 620, 516–520 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06317-9

Accretion Properties of PDS 70b with MUSE*

Jun Hashimoto1,2,3, Yuhiko Aoyama4,5,6, Mihoko Konishi7, Taichi Uyama2,8,9, Shinsuke Takasao10, Masahiro Ikoma4,11, and Takayuki Tanigawa12

Published 2020 April 22 • © 2020. The Author(s). Published by the American Astronomical Society.

The Astronomical Journal, Volume 159, Number 5Citation Jun Hashimoto et al 2020 AJ 159 222DOI 10.3847/1538-3881/ab811e

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-3881/ab811eThe Chemical Inventory of the Planet-hosting Disk PDS 70

Stefano Facchini1, Richard Teague2, Jaehan Bae8,3, Myriam Benisty4,5, Miriam Keppler6, and Andrea Isella7

Published 2021 August 11 • © 2021. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved.

The Astronomical Journal, Volume 162, Number 3Citation Stefano Facchini et al 2021 AJ 162 99DOI 10.3847/1538-3881/abf0a4

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-3881/abf0a4APOD: PDS 70: Disk, Planets, and Moons (2023 Oct 17)

https://asterisk.apod.com/viewtopic.php?t=43387